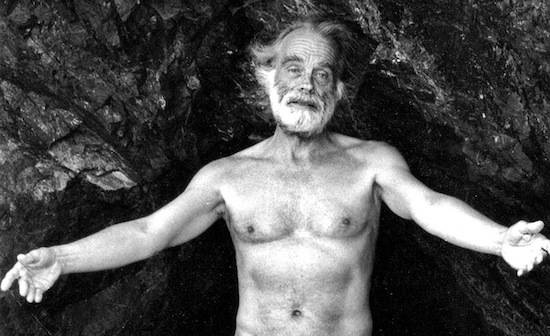

The great gay Renaissance man of San Francisco counterculture, James Broughton, disrobes and cavorts among us once again—on screen if not in flesh via Big Joy: The Adventures of James Broughton. (Though if any mere mortal could indeed gift us with his presence in an afterlife cameo, I’ll wager an emerald-encrusted Ouija board that Broughton would make a surprise appearance smack-dab in the middle of Frisco’s Castro Street, wrapped in a flowing white kaftan, waving a “Free Bradley Manning” banner, flirting with slender-waisted manboys and hitching a ride with the Dykes on Bikes.)

Postmortem fantasias notwithstanding, the poet, filmmaker and sexual liberator—a bearded bard of eroticism, a hirsute hippy descending from a hallowed haven of heavenly movie palaces and sinfully comfortable queen-size beds—really is back in a big way in an entertaining and enriching documentary currently garnering audience acclaim and jury prizes on the festival circuit (its recent California premiere at Frameline’s San Francisco International LGBT Film Festival received a standing ovation from the capacity crowd).

Co-directed by Eric Slade (Hope Along the Wind: The Life of Harry Hay) and first-timer Stephen Silha (who bunked with Broughton at a Radical Faeries retreat in the seventies), Big Joy blends fascinating archival footage; Beat Generation history lessons illustrated by performance artist Keith Hennessy; insightful interviews with Broughton peers and devotees including Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Neeli Cherkovski and the late George Kuchar (undoubtedly a kindred soul); visually rapturous renderings of Broughton’s diary entries; and a plethora of the artist-shaman’s wondrous works of poetry and filmmaking. Deemed “the grand classic master of independent cinema” by no less an authority than Jonas Mekas, Broughton’s enduring legacy as a brilliant funambulist and feisty iconoclast—he ditched Pauline Kael for a guy, famously stating that “nothing tickles the palate like nipples and cocks”—is playfully sanctified for a new generation of acolytes in need of an empowering role model.

Big Joy impresses as an expertly crafted documentary imbued with its subject’s zest and restlessness—Slade and Silha swiftly cover decades of artistic exploration, spiritual questing and romantic entanglements—while also serving as a timely reminder of an earlier and in many ways riskier era of LGBT self-identity and expression, far removed from what San Francisco writer/curator Johnny Ray Huston recently termed “the increasingly normative and corporate-capitalist Pride lockstep” of contemporary queer culture. With his radical aesthetics, polymorphously perverse love of bodies in rest and motion, and fascination with divinity and difference, Broughton was blessedly bereft of assimilationist angst. He didn’t need the Supreme Court to weigh in on the legality of his nuptial bliss, nor did he conform to conventional notions of the “good gay,” carefully coiffed as the romcom heroine’s BFF. “I believe in ecstasy for everyone,” Broughton exclaimed with glee, a sticky sentiment not often heard these days in either mainstream or alternaqueer circles.

Broughton’s oeuvre can be seen anew in Big Joy as refreshingly subversive, even though his propensity for surrealist dreamscapes, bare bums and free-for-all frolicking reflected merely wide-eyed innocence with nary a hint of interest in shocking either the bourgeois or the beefcake (he was closer in intention to Derek Jarman or Jean Genet than to Todd Verow or John Waters). As Tales of the City scribe Armistead Maupin attests in the doc, “James Broughton was a trickster. He had a way of getting at the serious by focusing on the silly, and that’s very seductive.”

Broughton’s inexhaustible creativity and polysexual escapades made for an action-packed and rewarding life, thought not one without its challenges (young Jimmy’s cold-hearted mother deducted twenty five cents from his allowance every time he acted effeminate, and he later struggled with bouts of depression). Even a quick overview is necessarily stuffed with amazing achievements.

Born in Modesto, CA in 1913, Broughton’s childhood was most significantly marked, so he often said, by the visitation of an angel who appeared to the three-year-old in the form of a naked boy, “a glittering stranger who told me I was a poet.” Spurred on by this hallucinatory Hermy (the angel’s nickname), Broughton discovered and was transported by early cinema. As he wrote in his 1993 memoir Coming Unbuttoned, “In the wonderland of silent movies my childhood discovered its most sensory home…How I longed to climb into that more vivid world.”

In his early thirties, Broughton alit for San Francisco and palled around with the who’s who of the underground scene (Ferlinghetti, Ginsberg, Miller, et al). Galvanized by Maya Deren’s landmark Meshes of the Afternoon, Broughton collaborated with Sidney Peterson on the 1946 whatsit The Potted Psalm, then struck out on his own as the director of Mother’s Day, a satire of matriarchal stereotypes in which adults act like children. Other early films include Loony Tom, The Happy Lover and Four in the Afternoon (Broughton’s titles always connoted pleasure and a hint of naughtiness). Around this time, Frank Stauffacher inaugurated the Art in Cinema film series at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, showcasing Broughton’s curios alongside equally groundbreaking works by Kenneth Anger, Jordan Belson and Harry Smith. The burgeoning experimental film movement was off and running.

Broughton’s biggest early success came in 1954 when his seminal ode to desire, The Pleasure Garden, was awarded a special jury prize at the Cannes Film Festival, where he was congratulated by lifetime hero Jean Cocteau for being “an American who made a French film in England.” Sniffing out the next big thing, Hollywood suits came calling with offers of big-budget studio productions, but Broughton turned them down. (Imagine what he might have done with a Sirkian melodrama or a sci-fi spectacle.)

Back in San Francisco, Broughton ended his relationship with Pauline Kael (then a film commentator at KPFA), took up with the wonderfully named playwright/actor Kermit Sheets, founded Centaur Press to publish his own and others’ writing, hosted old-school poetry slams in North Beach and essentially personified mid-century NoCal bohemia. (He would later make indelible contributions to post-Stonewall LGBT verve and visibility by joining the Radical Faeries and became a charter member of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, as Sister Sermoneta of the Holy Phallus.)

Following a long break from filmmaking, Broughton returned to the medium in 1968 with The Bed, in which photographer Imogen Cunningham, philosopher Alan Watts and a bevy of proudly pubic-haired singles, couples and threesomes are joined by a group of Anna Halprin dancers as they unabashedly revel in sensual delight in, on and around an ornate bed that rolls on wheels through a fecund meadow. Similarly frank films such as The Golden Positions, Nuptiae and Dreamwood soon followed, all steeped in Jungian mythology and touchy-feely proto-feminism, featuring androgynous figures such as the Infeffable Lollapalooza, and variously bolstered by the contributions of composer Lou Harrison and experimental film demigod Stan Brakhage.

Now married to costume designer Suzanna Hart and stifled in suburbia, Broughton took up teaching at San Francisco Sate University and the San Francisco Art Institute. At age sixty, Broughton met Joel Singer, a student some thirty five years younger than his perennially dashing mentor. Following a three-day tryst at the infamous Beck’s Motor Lodge, the pair became a devoted couple for the next twenty five years, living in a mobile home in Novato, on a rubber plantation plant in Sri Lanka and anywhere else their whims took them. With Singer and a bottle of champagne at his side, Broughton passed away in 1999; his final words were, “More bubbly.”

In the 1992 edition of his typically idiosyncratic guidebook Making Light of It, Broughton offers budding filmmakers the following advice: “Your business is to make something that neither you nor I have ever seen before. Your business is to make a wonderful new kind of mess in your own way.” Today’s queer cinema could do with some messy revitalization, and Broughton’s films should be required viewing for all would-be purveyors of a new sort of poetic-erotic cinema. (Sixteen of his twenty three films are officially available on DVD or via streaming services, and Slade and Silha hope to make the entire corpus available soon.)

Another bit of advice from Broughton to all of us: “When in doubt, twirl.”