How far are people willing to go to produce their art? For Blood Simple, the Coen brothers went knocking from door to door to raise money for production. Francis Ford Coppola invested millions of his own dollars and mortgaged his home to complete Apocalypse Now. Werner Herzog pulled a 340-ton steamship over a mountain to achieve realism in Fitzcarraldo.

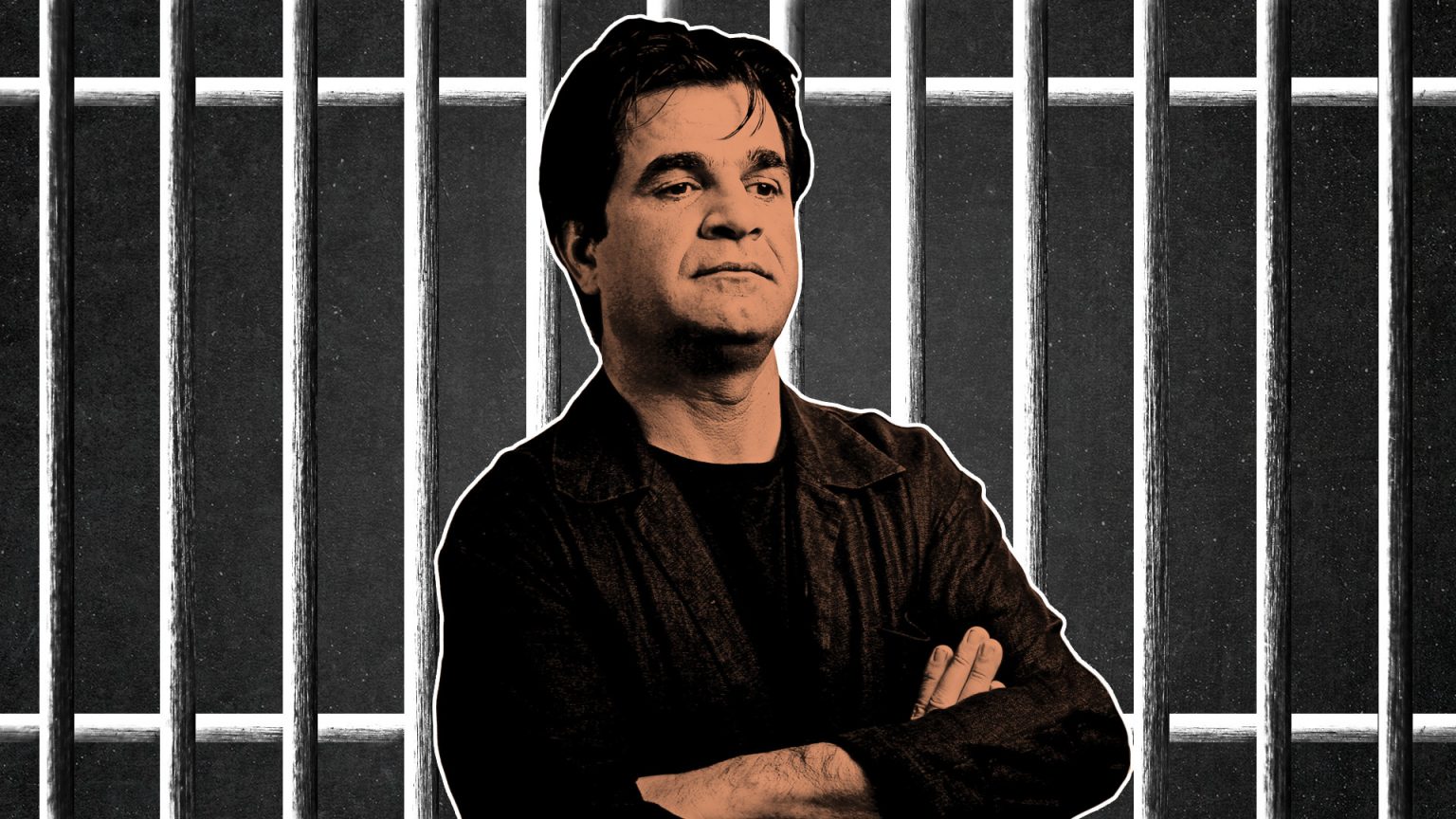

But the dedication of these filmmakers pales in comparison to that of Jafar Panahi, who, despite a six-year prison sentence and a twenty-year ban from filmmaking by the Iranian government, has still made four feature films.

For Panahi, the punishment imposed by his government has meant that he has had to become more covert in his filmmaking. Whether by shooting films entirely within his home, enclosed by dark curtains on all the windows, or posing as a taxi driver in Tehran, Panahi has managed to continue making striking cinema while circumventing the powers that be.

As a major presence on the Iranian New Wave scene, Panahi’s work has continually challenged the conservative laws and traditions in Iran, namely those regarding women and media censorship. As a long-time advocate for liberalizing the distribution of filmmaking equipment in his home country, Panahi’s ban has forced him to continue expanding the possibilities of how to get his movies made. Using iPhones, CCTV cameras, and Blackmagic pocket-sized digital cameras, Panahi has realigned the audience’s perceptions of production and technology when it comes to making a movie. He has shown us that it is not how one makes a film that matters, but the act of filmmaking that is of real importance. Panahi’s films are literal representations of the laws which he, in making them, defied.

In Closed Curtain (2013), a screenwriter (Panahi) shuts himself away from the world with only his dog, until a young, suicidal woman fleeing from authorities, arrives unexpectedly and disturbs his peace. The camera never leaves the house, mirroring how Panahi’s creative mind has been trapped by the ban placed on him. In the middle of the film, burglars break in and ransack the house. The only thing of value that they leave behind are the posters of Panahi’s old films on the walls. “You can’t steal reality,” a young woman remarks. They may try to take Panahi’s ability to make films, but they cannot take away what he has already made, nor the truths which he exposed.

His next feature, Taxi (2015) is told in real-time, with Pahani again playing himself, posing as a taxi driver. Similar in style to Closed Curtains, the camera never leaves the cab, with Panahi utilizing two covert cameras on the dashboard and an additional digital camera. Throughout the day, some of the passengers recognize Panahi as the famous filmmaker, others think he is merely a taxi driver. The result is a surreal film with intense, fictional sequences that remain rooted in the harsh reality of being a rebel filmmaker in Iran.

Panahi’s latest, Three Faces (2018), which premiered at Cannes earlier this year, follows three actresses, all at different stages of their careers, all three of which examine the difficulties of producing films in an environment where creativity is restricted.

The pseudo-documentary style of Panahi’s films creates the unique effect in which each film serves as a commentary on itself. Panahi is aware of his status, and though he must make his films covertly, he chooses to address his circumstances head-on, almost as if he is antagonizing those who would try to stop him. Since his filmmaking ban has been imposed, Panahi has continued to give audiences a real-life look into the everyday world of Iran and the artistic struggles which are, unfortunately, so deeply ingrained there. Panahi may have just turned fifty-eight years old, but if a national government can’t stop him, surely age cannot either.

Watch Now: Jafar Panahi’s Closed Curtain.