David Berman’s 2019 suicide left American music without one of its great depressive lyrical geniuses. The singer, songwriter, poet and academic was known as the guy who started ’90s indie-rock darlings Pavement as a side project, then went on to record a string of albums under the name Silver Jews. He attracted an ardent fanbase—aligned with other highly literate, melancholic artists on Chicago’s Drag City label, such as Will Oldham (a/k/a Bonnie “Prince” Billy, Palace) and Bill Callahan (Smog)—even though the band never appeared live until the 2006 Israeli tour documented in Silver Jew. The film, released a year later, was produced by Berman’s friend Matthew Robison and directed by Michael Tully, the now Austin-based filmmaker whose subsequent work caroms from Southern Gothic (Septien) to ’80s coming-of-age comedy (Ping Pong Summer) to supernatural yarn (Don’t Leave Home). This year, his performance doc Lover, Beloved, with songwriter Suzanne Vega in a one-woman show as Carson McCullers, premiered at SXSW in March (as Silver Jew had 15 years prior).

“That checks my bingo card for ‘Robert Altman’s Secret Honor‘ or, you know, ‘Jonathan Demme Swimming to Cambodia,'” says Tully, video-chatting this week from his Texas home. In contrast, Silver Jew, a featured highlight this month on Fandor, offers a thoroughly informal perspective on a more contemporary literary figure, as Tully’s mini-DV camera follows Berman on an emotional journey to Israel, where the performer, who had recently embraced Judaism, goes deeper into both a spiritual awakening and is elevated by his encounters with fans on an inaugural tour. In this conversation, Tully flashes back on his “awakening” to Berman’s songs, the totally casual way he ended up making Silver Jew, and his ongoing connection with the artist.

Keyframe: What was your entry point as a David Berman or Silver Jews fan?

Michael Tully: I was raised in “Bumblefuck,” Maryland and had three older sisters. Growing up from 1985, when I was 11, I was into rap. If it’s singing, I don’t care, you know? I remember my sister driving me to school and listening to Camper Van Beethoven’s (1989 album) “Key Lime Pie” and thinking I might want to listen to this when she’s not driving the car. Pretty soon after that, I had the awakening. It was twofold: Silver Jews’ “Starlight Walker”and Pavement’s “Slanted and Enchanted.” I can’t even remember which one I heard first. Lyrically, there was something going on that was witty, literate, and just clever, being able to speak about familiar things in a way that you’re like, “Oh God, I wish I thought of that.” [Berman] was coming up with something unattainable. His brain was connected to language in a way that was awesome. Awesome not in the playground sense of the word, but cosmic.

Keyframe: What was your early relationship with filmmaking?

Tully: I studied undergrad at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. I went to college for a year at Flagler College in Saint Augustine, Florida. I left home and wanted to be a writer. I can do that anywhere, so I wanted to go where the weather’s warm, I can play tennis and read and practice writing. When I was at Flagler in 1992, I had the epiphany that film combines writing, photography, music and performance. It’s a one-stop shop for creative expression! Then I went back to Maryland, when my awakening happened with Berman. “The Natural Bridge,” the second album, came out. I was really obsessed with that record. This is before the digital revolution. So even when I’m in film school shooting on 16mm and editing, it still felt like to make a movie? I don’t even know how I would do that. I don’t have enough money. And then it all turned, as we all know, in the early 2000s.

Keyframe: Indie rock exploded in the ’90s. There was Nirvana, obviously, but all these other bands and artists were creating this fascinating kind of middle American sound. I think about someplace like Louisville, all these towns with their own brilliant songwriters and performers, often depressive but hyper intelligent, working in a folk mode that was also DIY and punk.

Tully: Definitely. It felt more attainable. Everyone talks about that with punk rock. Oh wait, I can do this. I look up to these people, they’re awesome, but this is something that I can do. I had this little creative outlet with music. But I never wanted to pursue it too seriously.

Keyframe: Where did the connection come to make this film?

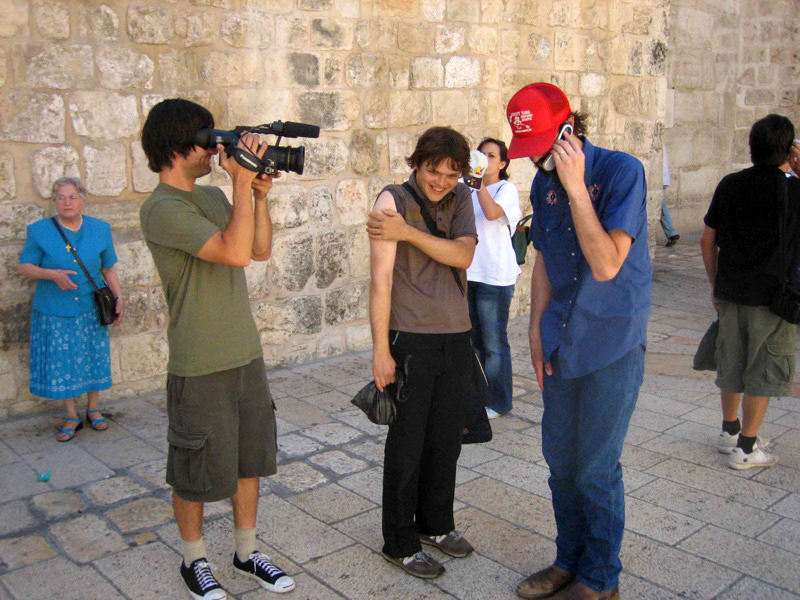

Tully: It wasn’t from the film or music world. My sister Carol [moved from New York to Nashville around 2003 for an internship] and within weeks she wrote me. “I met David Berman and Harmony Korine last night.” When I would visit her, I became a little friendly with Harmony and David. Matt Robison, who I made the film with, was a producer, basically a co-director, but he knew David well. David had had his own kind of awakening, after he’d had a suicide attempt and gotten clean and sober. This is the era where we got him. He was in the best place possible and decided to tour. Matt got the initial blessing from David. I’d become friendly with Matt, so we went there as a two-man band. Our whole point was to keep it small. Let’s treat this almost as a home movie, just see what happens. Maybe we get a music video. It wasn’t until, as you see in the film, the epiphany of David at the Wailing Wall that I was like, “OK, there’s a film here.” It ended up being 51 minutes. Movies are way too long. Let it be what it is. David just let us do what we were doing.

Keyframe: I had read that Berman never watched the film. True?

Tully: He was on record saying that he never actually watched it, like: “I would just be picking on, oh, you see my bald spot there, my yellow teeth. I’m not going to be giving responsible notes on this film.” My sister, who knows David way better than I ever did, thinks there’s no way he didn’t watch. Now I guess we will never know.

Keyframe: I interviewed him in New York in 2008, when “Lookout Mountain Lookout Sea”came out. Given his reputation, I was surprised that he was so easy to hang out with.

Tully: If you get him out, he would be social, and you’d be like, “Oh my god, that guy is so fun and great and funny.” It’s like standup comedy all the time with him. Maybe he put on a good show and then it would take a lot out of him to be around people. How long did you guys speak for that?

Keyframe: An hour. I didn’t know what to expect, so I went in hoping for the best. Sometimes people can be very peculiar and not talk much or be in a bad mood. He told some funny stories, like how his mother would make frozen balls of raw beef, then serve them with lots of ketchup and white onion.

Tully: My other sister Colleen had met with him—he came through town and they went out to dinner. He asked what she did and she’s a teacher. She said, “I’m going to an ADHD conference this weekend.” He’s like, “Oh, they should call it concentration camp.” He was rapid fire: wordplay, puns, and thinking of ways to spin language.

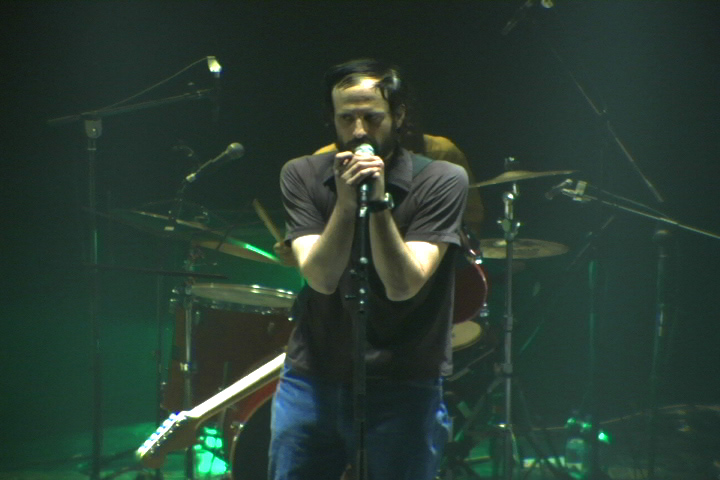

Keyframe: That comes through in the movie, which has a lovely flow to it. The casualness helps when you have these intense moments, like when Berman is reading the prayer and crying at the Wailing Wall, or his joy when he comes offstage after a show. There’s a quiet charisma to it all.

Tully: I should point out it was edited by Jane Rizzo, who—darn it!—just lost the Emmy for editing on “Succession.” This film was like the cost of the tapes and the trip to Israel. Maybe I should point out one thing that I do wish we had noted. There was some stuff popping off with Lebanon and they had closed off the West Bank. There was an initial plan for the band to go to the West Bank, but that was not allowed. That’s one regret I have. Ultimately, you can only do what you’re doing. The film became a story about an individual who was trying to connect with the world, so it wasn’t political. But it’s setting something not political in the most political [place].

Keyframe: I read somewhere that you took Dave Chappelle’s Block Party as inspiration.

Tully: What I loved about Block Party was that it did what it wanted to do. It didn’t have an agenda other than establishing a situation, trying to capture it honestly, then going behind the scenes, coming back onstage, and being an organic hodgepodge of the moment and experience.

Keyframe: Did you stay in touch with Berman through the years?

Tully: I would check in. He went quiet for a long time before “Purple Mountains”came out [four weeks before Berman’s 2019 death]. I was trying to make Don’t Leave Home, my last feature, in Ireland and that took many years and drafts. I sent him an earlier draft and we got on the phone. His first question: “Why do you and Harmony write your own scripts?” Like, you should either be a writer or a director. I didn’t say this at the time, but I would have: “Why do you sing your own songs? People give you shit for your voice not being a great singing voice.” That’s the whole point, right? The expression is so embedded in the words and your expression of it. He didn’t really know what to do with the script. We talked a few times, not a ton. I wish I could pull up the email, but I wrote: “Sorry, man, I’m having a baby.” Because he was like, “Why do you people have children? You know, Earth is dying.” He said something in his great language, which I can’t remember exactly, but it was like: “Once I know that a baby’s coming into the world, I’m all in and supportive and I’m happy for you.”

We were flying to Maryland to see the Purple Mountains show. When I heard the album, I emailed him and came clean: “This sounds like a suicide note.” When I heard that record, my stomach dropped and I felt like he was already gone. I did write him: “You’ve committed to this tour at the very least. Do the tour and see what happens.” He wrote back and said, “You’re thinking what I’m thinking.” He put us on the list. We were going to go see the DC show that week later. [Berman, who had struggled with addiction and depression, and survived a previous suicide attempt, died on the cusp of his tour]. I think what people responded to in his writing and even in “Actual Air,” in his poems, is that he was prescient. He was predicting where we’re headed now, even a few years since his passing. Everything he’s said, his warnings are only becoming louder.