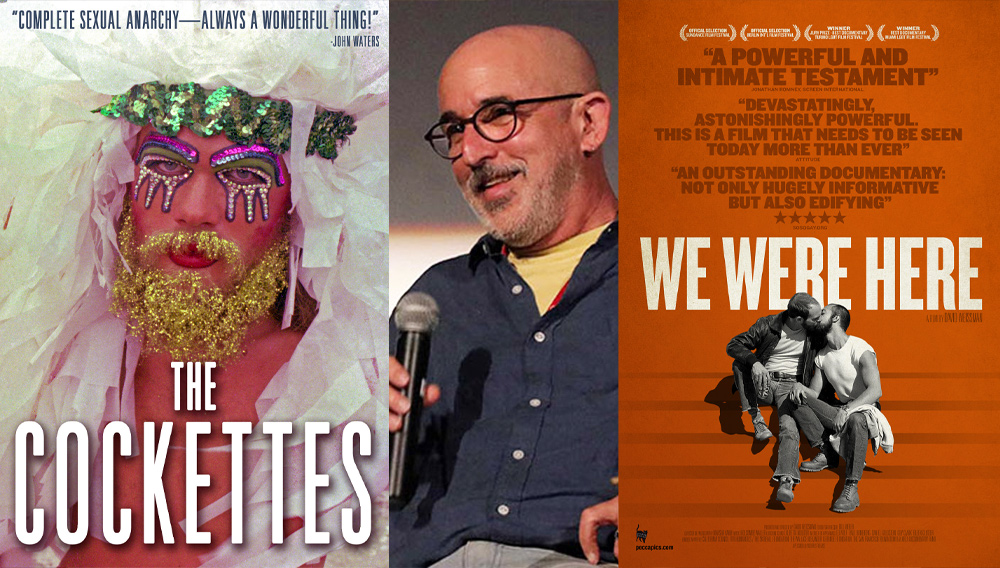

Essential documents of what now seems almost a fantastical time and place—San Francisco from the late 1960s into the early ’80s—The Cockettes (2002) and We Were Here (2011) respectively tell the stories of the outrageous glitter-bombed, gender-bent performance troupe and a heroic response to the harrowing impact of the AIDS epidemic on a blindsided populace.

Both acclaimed, Sundance-premiering films (as seen in Fandor’s “Queer as Day” streaming spotlight for Pride Month) were made by David Weisman and Bill Weber, who tackled their endeavors with the enthusiasm of first-time filmmakers not knowing what they couldn’t do, answering the call of a historical moment. Keyframe caught up with the peripatetic Weissman at his current residence in Amsterdam, where he spoke over Zoom about the exceptional lives of both films, the role of serendipity in shaping his life path, and the transformative power of community.

KEYFRAME: It’s been a long while since these docs premiered. Do you rewatch these films at all?

DAVID WEISSMAN: They had their initial big life in the festival, theatrical and broadcast circuit in the years after they were released. Fortunately, both are evergreen movies in different ways. The Cockettes audience has been less gay people than straight people who are interested in counterculture. We Were Here has had a huge educational afterlife because it was the first film to come out that looked back at what really happened.

For different reasons, I would imagine that they’re both incredible audience films. One for laughter and one for tears.

I have often described them as love letters to San Francisco, which in many ways was my muse. I dreamed of moving to San Francisco as soon as I heard about hippies. I was always a student of the counterculture, long before I had any sense of myself as gay. Living there for as long as I did was also a dream. Both movies elicit a lot of reactions. We Were Here has a strong, obviously emotional resonance. When the movie ends and there’s a talk about the demise of the magic of that moment, there is a wistfulness that’s inevitable.

Yet with both films, even though there is a sadness, it was also important to me that we had a sense of redemption and inspiration, not just movies that were like, “Look what you missed with the Cockettes.” We wanted to look at what’s possible. With wanted We Were Here to be a tribute to the remarkable resilience, creativity and idealism of San Francisco.

You moved there in ’76, so you were very much part of the scene.

The ’60s wound down in the early ’70s, most places, and turned into mush. In San Francisco, those elements of the ’60s only got richer and more embedded in the psyche, the consciousness, and the day-to-day life of the city. San Francisco was a radical city when I moved there, in terms of everything—housing politics, food politics, sexual politics—and that was the time just before Harvey Milk was elected to be city supervisor.

What were you doing there?

I worked as a waiter in a restaurant just outside of Castro Street, the New York City Deli. It attracted an eclectic crowd. I had always been very political. At the time of Harvey’s assassination, I gave notice at the restaurant and wound up working on a rent control campaign. Eventually I got hired to be a legislative aide to a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. I had no college degree or anything.

How did you end up as a filmmaker?

Everything that I’ve done was chance and serendipity, instinct. I’ve never had a plan ever. I thought, maybe I’ll take a class at the community college. That was very loose. I enjoyed making these weird little one-minute films because it was all Super-8 then, so it was expensive. The first time I had a short film play on a screen and get a strong audience reaction and applause, I thought, “Oh, I really like this.” But it was never like, “I want to be a filmmaker.” I just wanted to be a hippie.

What introduced you to the professional side of it?

I started to work more on other people’s films in the Bay Area, primarily documentaries. San Francisco Bay Area was a documentary world. The shift was in 1990. I was the first person selected for the Mark Silverman Fellowship for New Producers, which was a collaboration of the people around Joel and Ethan Coen with the Sundance Institute. It was in memory of a guy named Mark Silverman who had produced their first two movies and died of AIDS.

That fellowship gave me a great education in working on Barton Fink. It gave me an entree through the Sundance Institute into a world that otherwise I hadn’t had any prior access to. I co-wrote a screenplay with Richard Glatzer, who died a few years ago of ALS, but he and his husband made a lot of movies. I made some HIV prevention ads that were innovative and very unlike the things that had been done before. They were provocative.

Then, in one of those moments of serendipity, it came up that somebody should make a documentary about The Cockettes. As it was with my other movie, nobody is going to do it if I don’t—and if somebody else does it, they’ll do it wrong. I reached out to my friend Bill Weber, an editor of high-end music videos and commercials. He was a Grateful Dead fan like me and had a hippie background. I said, “Hey, do you know who The Cockettes were?” He said, “Of course, they changed my life when I was a teenager.” Bill and I wound up being co-directors.

What was the experience of making that first feature like?

Naiveté is a great quality to have. It was fantastic. Finding the archival material and dealing with some of the rather eccentric people who owned it was an adventure. I was the producer/co-director, so I was doing all the outward work. Bill, as co-director and editor, his work was inward facing. Looking back, there were so many things that had to go right for that movie to be in existence now. It was filled with big and little miracles.

It’s such a riot. There’s a great amount of drama. It’s got all the feelings.

Had you seen Tricia’s Wedding before? [The queer, guerilla drag spoof of then-First Daughter Tricia Nixon’s nuptials is The Cockettes’ crowning glory and a subversive cinema classic]. I saw it when I was 19. For both Bill and me, it was hugely impactful and in ways I only started to realize as time went by. It was an honor to be able to bring The Cockettes back into their rightful historical place.

We Were Here couldn’t have been an easy film to make.

It was not. And again, it was not something I had given a moment’s thought. It emerged out of a conversation with a much younger boyfriend. I thought, this is not something I want to revisit. I don’t want to make a movie that’s going to be depressing. It’s not what I want to put out into the world. But I realized quickly that it could be an extraordinary journey.

When I was a kid, I got Mad Magazine like everyone else, and they had those folded things on the back. One of them I’ve never forgotten was a fake ad for Concertina Tomatoes, which was “how did they fit eight big tomatoes in that little bitty can?” That was how I felt about making We Were Here. This is a 30-year history of extraordinary complexity on every level: political, scientific, human. How do I make a movie about this?

I didn’t know how I was going to do it, but when junctions came and choices had to be made, they were always completely clear. That’s partially because the movie reflects exactly the years I was in San Francisco and the experience I lived through. I realized early on that I wanted to go for depth rather than breadth. I wanted a strong emotional connection between the people onscreen and the audience to see how far one can go in creating a sense of empathy in a room. Not sympathy, but actual empathy. Maybe there will be 12 people in the film, maybe there will be eight, then it got down to five.

How did you cultivate relationships with your subjects?

Everybody would be looking for an excuse to leave the theater when they’re watching a movie about the AIDS epidemic. I thought, I need people who the audience is going to fall in love with in the first five minutes. They can say, come with us on this journey. The casting was crucial. All five of those people I had some degree of connection with, and I happened to bump into them somewhere along the line and go, “Oh, how about you?” I only interviewed nine people in total, which is insane given the immensity of the history. These five were the ones that worked together the best. I’m glad I didn’t have to do more because the interviews were emotionally difficult to do.

There was a recent article about doc filmmakers tackling heavy subjects and suffering PTSD. I imagine you could relate.

When I was starting to read this article, I thought, this is about a different kind of filmmaking than I do. It’s people going off to war and seeing people killed in front of them. Then I thought, “Oh, no, this was revisiting a hugely traumatic period of my life.” The whole experience of making the movie, holding space for people who wanted to talk to me about what I was doing, then holding space for the audiences was hugely emotionally challenging all the way through. Yet it was very empowering for me to feel like I have the the capacity to really hold this and carry it. I don’t think I could have made that film if I was a couple of years younger. People endlessly said, “What are you doing to take care of yourself?” And I’d say, “I don’t know.” I know a lot of gay men of my generation did not want to see it because they felt it was going to be opening old wounds. And I’ll say 99% what I got from people was “I was so afraid to see your movie and it was so validating and so cathartic and so healing.” I could say that about my own journey as well. It was deeply healing for me to do that.

I think We Were Here has new relevance after COVID-19. Again, there was a monstrous health crisis that polarized the country.I wonder if it might be helpful for people in a new way. Both films illustrate the very human power of community, compassion, and a desire for people to take care of each other—which is the opposite of what’s going on in America amid the rise of anti-LGBTQ political rhetoric.

Those are very perceptive points. I wish my distributors would realize that as well. They missed an opportunity to promote We Were Here in relationship to the pandemic. I have a lot of young friends, and a number of them reached out and said, “What’s your take on this in relationship to what you lived through with AIDS?” They’re hugely different situations. Of course, there are some parallels. What I always hoped people would take from We Were Here was not specific lessons around safe sex, but a sense of the importance and beauty of being part of a community that takes care of itself and each other.

The other message that was important to me is the sense that all of us are going to be confronted with some kind of calamity that we don’t anticipate. If we try to imagine it in advance, it may seem overwhelming and insurmountable. But we’re able to rise to the occasion, sometimes ten years later. We all have tools in us that we don’t utilize until they’re needed.