For T Bone Burnett it was love at first sight. When Joel and Ethan Coen’s 1987 film Raising Arizona was released on VHS he watched it over and over, and eventually he was moved to pick up the phone and cold call the young directing/producing team. “I said to myself, ‘These people, they must have seen all the same movies I did growing up or something.'”

Burnett still has every scene of Raising Arizona committed to memory, and he relishes talking about why the film squares with his own sensibilities. “When I first saw it, it really spoke to me. First of all it had this insane soundtrack…it had that crazy Pete Seeger ‘Ode to Joy’ on a banjo with whistling and yodeling. It was just totally mad. And every joke in the film landed for me. For instance, when John Goodman and his cohort come up out of the ground and go into the service station to comb their hair, written in spray paint on the back of the door is ‘POEOPE’; you can see it backwards in the mirror. I thought, really interesting, this is how detailed they are, that they would take a quote from Dr. Strangelove—you know, ‘Purity of Essence and Peace On Earth”—and put it backwards in a mirror in spraypaint on the back of a door in Arizona with these guys combing their hair. They just didn’t want to leave any space un-meaningful. Everything in the frame has tremendous meaning. I’ve never seen anyone make films with this level of detail.”

Burnett, who at the age of sixty-five has evolved into a patrician figure known for championing, cultivating and mentoring young artists—and reinvigorating older ones—is highly sought after in the film and music producing worlds for his light touch and deep affinity with the history of American music. Over a rollicking and wide-ranging forty-year career in music, he has collaborated with an impressive array of luminaries including Bob Dylan, Roy Orbison, Elvis Costello, Elton John and many others. But it’s his work in movies, and in particular with Joel and Ethan Coen, that has given him a reputation as something of a Hollywood music guru.

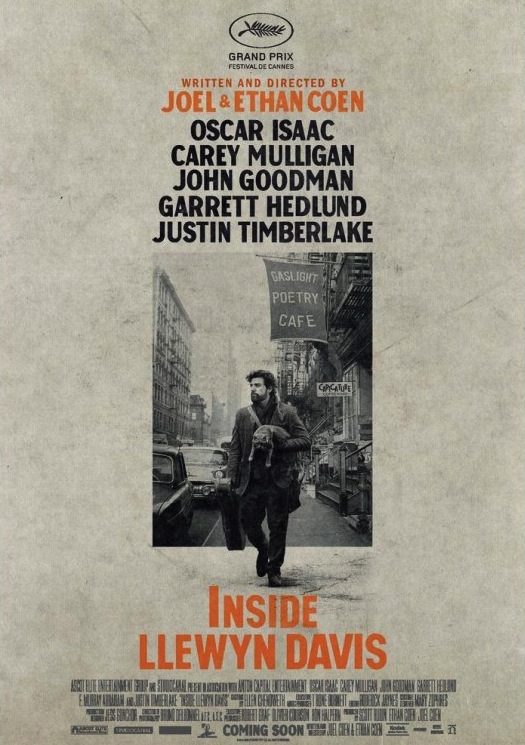

Beginning with their 1999 collaboration on The Big Lebowski, for which Burnett contributed as “Musical Archivist,” Burnett and the Coens have developed an inimitable creative synergy that has resulted in four uncommonly idiosyncratic and beloved films. It’s almost impossible to imagine the Coens’ 2002 O Brother Where Art Thou? without Burnett’s participation. That film, a beguiling melange of goofball humor, literary allusions and elaborate set pieces, was steeped in music and anchored by the old gem songs that Burnett plucked from obscurity and re-presented, some as original recordings and others in lovingly recorded new renditions. So it was a foregone conclusion that the Coens would bring him into the fold for their new music-steeped film Inside Llewyn Davis, a melancholic foray into the milieu of New York’s West Village in the early sixties and its burgeoning folk scene.

I sat down with Burnett last month in San Francisco with a group of other journalists in advance of the film’s release. Like other Coen Brother films, this one is replete with whack jobs, sad sacks and a few pure souls. It follows protagonist Llewyn Davis, a workmanlike musician with a sweet voice and a clear vision, over a wintry week during which he fumbles and fails and somehow manages to just miss success, in great part by perpetuating his own bad karma.

The years leading up to the moment when Bob Dylan appeared and changed everything was an unique and delicate period in American music: An insular, burgeoning folk music scene was coalescing in and around Washington Square Park, its participants filtering the music of Harry Smith’s 1952 Anthology of American Folk Music and preserving through their music the qualities that resonated with them.

“There were these different camps [of musicians] that played in Washington Square Park,” Burnett explains. “All the competition between the musicians was for turf in the park. It wasn’t for trends on Twitter, it was for a little grassy area in the ‘country’ of New York City, because back then the Village was the country. Nobody was thinking about being famous. They were thinking about what was good and what was authentic, and these kinds of questions. They were just trying to be good, there. That’s a beautiful thing, that’s the place where everything happens. All the great things happen in small communities, where people aren’t thinking about grand gestures. They’re thinking about taking care of what’s right in front of their noses. And all this energy converged there.”

Llewyn Davis, played with a deft sense of pathos by actor/musician Oscar Isaac, is a much quieter soul than we have come to expect from a Coen Brothers movie. “Llewyn wasn’t a guy who was thinking about making it in a big way,” Burnett observes. “He was just a guy thinking about what’s good music, according to him. It all boils down to taste, right? When he goes for his big audition and he has a chance at the big time, the song he chooses to play is about a woman having a Cesarean section. So here’s a guy who’s not going out of his way to be ultra showbiz.”

In the production notes, Ethan Coen relates a revealing anecdote about how he and his brother came upon the idea for the film: “One day Joel just said, ‘What about this? Here’s the beginning of a movie… A folk singer gets beat up in the alleyway behind Gerde’s Folk City.’ We thought about the scene, and then we thought, ‘Why would anyone beat up a folk singer?’ So it became a matter of trying to come up with a screenplay, a movie that could fit around that and explain the incident.”

One fascinating aspect about that particular scene is that it bookends the film. The second time we watch it at the conclusion of the film Llewyn, after a horrendously trying week, leaves the club during a performance by someone he’d never heard before. While he barely glances over his shoulder, the sand-and-glue vocal stylings of the young Bob Dylan are unmistakeable. “When Dylan came along,” Burnett says, “there was all this extraordinary music everywhere but a lot of infighting. Dylan was like Fast Eddie coming to town and he just ran the table. He said, ‘I’ll have some of that, and some of that;’ he had no compunction. He was doing the right thing: those people were looking backward, and they were doing the right thing too. They were going backward and preserving; Dylan was going backward and forward at the same time. He was looking back and preserving all of that and then reinventing it for us, now. We’re still living in his reinvention of it.”

Once the screenplay was completed, it was Burnett’s job to integrate the music into the film. One formidable challenge—and one that he savored—was that the Coens were determined to have all of the musicians performing live during filming. “They wanted to make a film about a musician,” Burnett says. “And they wanted as much detail as they could get about the musician. Therefore, they wanted to film him singing and performing live. They wanted to do the hardest thing you can do. It’s easy in this day and age, with everything we have, to create a virtual performance later in editing. You can holographically sample somebody and manipulate them to say—and sound like—anyone you want to. But a virtual rendition of a performance captures so little of the detail of the performance. If you put some super high quality recording equipment right on a live performance, it gives you all the depth and detail that you lose in the virtual world.”

“If another filmmaker had come to me and said, ‘We want to make a film about a musician and we want to record it all live, and we want to record three- or four-minute songs, and we want to do it without a click track, documentary style,’ I would have said, ‘I have to advise you against this. You’ll never find the person who can do it.'”

But they did find someone in the person of Oscar Isaac. Burnett says, “I don’t think any actor has ever learned to play and sing a repertoire this thoroughly and compellingly, and be able to film it all live without a click track, without the aid of tuning, without the aid of technology—just a complete analog performance of this character whose music Oscar had never heard a year before he did the film. Unbelievable.”

After completing four films with the Coens, Burnett says that they’ve developed a quasi-casual style of working that allows good ideas to bubble up organically. “Everybody puts every idea on the table, and it doesn’t really matter who came up with what. That’s the beautiful thing about working with them. You never really feel like they’re some sort of controlling presence. They always come in as the most decisive participants.”

However, Burnett continues, the brothers are in fact quite disciplined and they leave little to chance. “During production, each morning they give the actors slides with the lines below a drawing from the storyboard, including the camera angle they are going to be in when they say those lines. They have the entire film all cut in their head long before they shoot it. And this is one of the reasons they have such control, because economy is the essence of art, you know?”

When asked about his philosophy to scoring a film, Burnett is succinct. “Danny Elfman taught me that anybody can put a piece of music with some footage and have them connect in some way, and have it invigorate or do something to the story. There’s some touch involved in that, and taste, but that’s not what makes a score. A score tells the story of the film, but in a different language. A score has to tell the story from beginning to end, with one arc. One can drop in a piece of music here and a piece of music there, but if they’re not part of that overarching arc, they’re not really part of the score, you know? They’re just events.”