1998. I was a film student attending UCLA roughly ten years after Caveh Zahedi and Greg Watkins had made A Little Stiff using the campus as their principal location. During my first year, Pulp Fiction was still the highest aspiration for all budding cineastes in the program. Everyone seemed to be writing a script about a young filmmaker who is an eager pupil by day, a dangerous hit man by night. Instead, I chose documentary as my focus.

Like any good disciple, I became completely besotted with the nonfiction form, zealously intent on seeing every doc ever made. One morning in the coffee break area, I got to comparing favorite films with a jaded grad student. She was astonished that I had never seen what she considered to be the greatest American documentary made in the previous decade, Caveh Zahedi’s I Don’t Hate Las Vegas Anymore.

Only one video store in Los Angeles, Vidiots in Santa Monica, had a VHS of Vegas, so I went out by bus to rent it. I was floored by Caveh’s intensely personal 16mm exploration of the dysfunction between him, his hip-hoppy younger brother and gambling father who may (or may not have) taken ecstasy to help Caveh make a better movie.

I made a tape copy of the Vegas VHS and forced anyone I could find to watch it with me. Doing this, I discovered a truth about audience reaction to his work: people either embrace it wholeheartedly or are thoroughly mortified. With Caveh Zahedi, there is no middle ground.

Shortly after, my roommate began working a counter shift at Vidiots. One night, Caveh came in to rent a movie. She told him that a certain UCLA doc student (me) had a fervor for Vegas then gave him our address. I returned home that night to find Caveh sitting on the living room couch in black jeans, black t-shirt and black raincoat.

I suppose I should offer up a description here of what Caveh was like. If you want to know then just watch his movies. There really isn’t much difference.

And I really don’t like it when people say that Caveh is pretentious. Years ago, we went to see the Hollywood comedy Bowfinger. During the scene in which Steve Martin’s no-budget filmmaker character convinces Eddie Murphy to cross a busy highway, Caveh laughed longer and louder than anyone else in the theater. I never heard him doing that during a Bresson film.

We ended up most of that first night talking Godard, the Pixies and the amazing coincidence that we had once both written unanswered fan letters to silent film historian Kevin Brownlow. Maybe Caveh considered this a good omen because the following week he called me and asked if I would like to shoot something for his birthday.

On a foggy April afternoon, Caveh picked me up from campus in his ancient blue Toyota and drove us to an appliance shop to buy a blender. We then went to his Venice flat and, in a single afternoon, shot our first collaborative adventure, I Was Possessed by God. Inspired by psychedelics guru Terence McKenna, Caveh proceeded to ingest a heroic dose of ground hallucinogenic mushrooms. His instructions were simple. Don’t answer the door or the phone and, no matter what, don’t stop filming.

After two hours of Caveh rolling around, moaning, he suddenly sat up and in a demonic growl began to extol the virtues of Pier Paolo Pasolini, David Letterman and Ruth Gordon’s vagina. Caveh originally wanted to release all I had shot as a feature, insisting it proved the existence of God. Though no producers were interested in backing this spiritual venture, Possessed later played on the big screen at the Olympia Film Festival. I still recall watching it thoroughly terrified, sweat dripping down my back, as I relived what I had experienced.

Caveh moved to San Francisco to be with his future wife Mandy who would play a prominent, if often involuntary, role in his 1999 video diary, In the Bathtub of the World. Making a bunch of trips to the Bay Area, I shot and edited sections of Bathtub, had a small acting role in Greg’s A Sign from God and shot A Day in the Life of Greg Watkins, a behind-the-scenes doc about the making of the film. Cameras always seemed to be running on something and eventually I made the move up north as well.

San Francisco was still an incredibly creative place to make and watch movies in the late 1990s and early oh-oh’s. Apart from Caveh, there was his best friend, Jay Rosenblatt toiling away in his basement on another found-footage masterpiece. Ten blocks away, collage artist Craig Baldwin was also creating and curating his Saturday night experimental salon at the Artists Television Access, a grab bag of wondrous avant-garde treasures. The Bay Area had a half-dozen rep theaters and over sixty film festivals as well as daily screenings at libraries, museums and press clubs. One critic I knew even programmed a long-running, well-attended noir series at a trade union hall. The whole metropolis seemed consumed by images.

Cinema seemed like the answer to everything. So much so that Caveh decided on one of Mandy’s birthdays to give her an unexpected surprise. The surprise was me and my camera creeping into their bedroom at 6 a.m. to tape everything she did for the next twenty-four hours. Understandably, Mandy was initially not very enthused about the project. But subsequently, after we finished Mandy’s Birthday, the taping became something of an annual event. The last birthday we rolled on, an overnight camping trip that’s still in the can, became an extended therapy session as Mandy, Caveh and their friends picked apart his motivations for recording them in the first place.

When In the Bathtub of the World came out, a lot of friends and critics noted the palpable amount of tension between Caveh and Mandy. I still recall the shocked look on Mandy’s face when, after one screening, a therapist came up after and offered her counseling. In all fairness, the couple did have a number of dramatic fights during those years. But there were an exceptional number of good times not caught by any camera. Some people wonder why Caveh and Mandy are still a couple. I don’t. It says a lot that Caveh and Mandy have been together longer than I can remember.

In the decade after A Little Stiff, Caveh had tried to get his autobiographical opus I Am a Sex Addict off the ground. After Robert Downey Jr., Vincent Gallo and Harmony Korine declined to play the lead, Caveh toyed with doing a transgressive take on the finished script by playing the role himself and having real prostitutes recreate his dive into dependence. With no money, he tried to shoot this version on weekends on 16mm with financing borrowed from successful indie friends. Ever the perfectionist, Caveh barely advanced as he kept re-shooting the few scenes he had done.

Eventually Caveh and Greg succeeded in interesting a generous and dangerously patient San Francisco businessman, Richard Clark, to bankroll I Am a Sex Addict with Caveh both directing and acting. With an initial budget of $50,000, the plan was to shoot and edit the film in less than a year, in time to compete for the upcoming Sundance Film Festival.

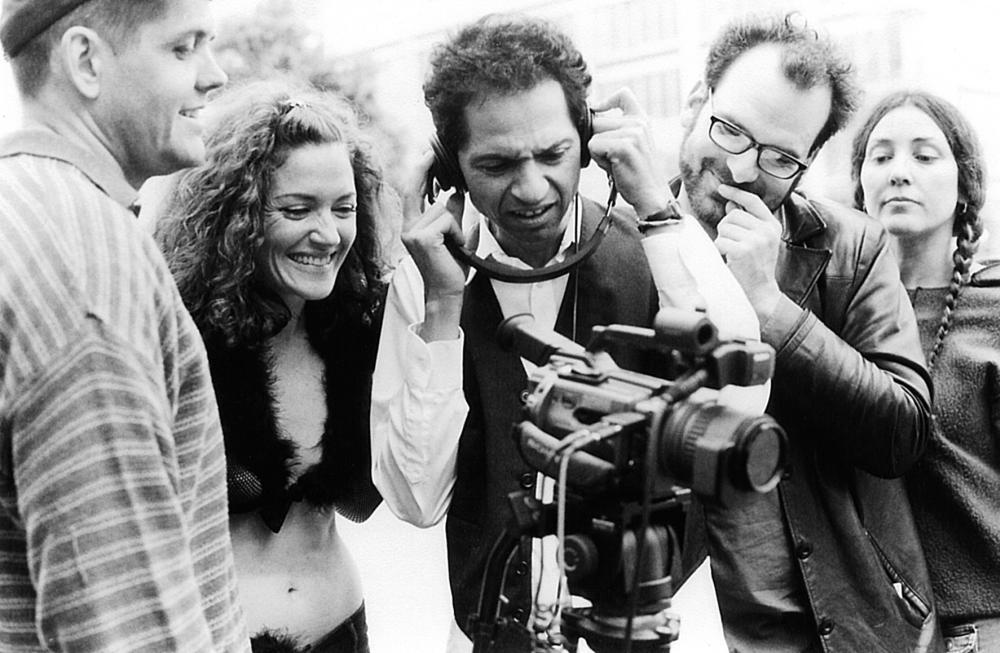

Looking back on it now, to shoot a feature requiring numerous locations with a crew of three (Caveh, Greg and me) seems impossible. It was. I Am a Sex Addict ended up taking a half-decade to complete and went eight times over budget.

I was originally hired to do sound but after getting an Oscar winner to loan her award statue for a fantasy sequence, I was elevated to producer until a replacement could be found. No one ever filled the position and when the film was finally wrapped, I ended up with nine credits. My uncredited tenth, music arranger, occurred after the frustrated composer quit and I was left to place the score as we began the sound mix.

My life for the five years of my Sex Addict sentence would begin at 11 a.m. I would set up the weekend shoots in the afternoons (Greg was teaching and could only commit to Saturdays and Sundays), then edit with Caveh from 5 p.m. to 11 p.m., forty-five minutes home, late dinner, then watch the next day’s scenes and outtakes, a movie and off to sleep at dawn. Almost all of the outdoor shooting of I Am a Sex Addict was done without permits and mostly at night on dicey street corners and darkened alleyways with swanky SF locations serving as Italy and France.

I also spent innumerable hours in strip clubs, massage parlors and flop hotels getting permission to shoot while trying to convince strippers and sex workers to play supporting roles in the film. When the local weekly put Caveh on the cover, I took hundreds of copies around clubs as proof I was not a skeezy pornographer but the legitimate producer of a low-budget indie comedy about sex addiction. Though sometimes the distinctions blurred, it actually worked.

Caveh also had the idea that what went on behind the camera could be as compelling as what went on in front. So apart from my other duties, I also rolled on everything that happened on set sometimes literally dropping the boom mic to capture edgy clashes with spun-out, unhappy strippers or a particularly powerful mushroom or ecstasy trip involving Caveh and an actress. Though hundreds of hours of material were taped, only a tiny fraction was used in I Am A Sex Addict.

On top of all this, a number of other projects were shot and edited. Some were released while others still remain on Caveh’s shelf. I have always maintained my best camerawork was in the short doc The World is a Classroom, part of Caveh and Jay Rosenblatt’s 9/11 Underground Zero collection. Sex Addict had barely started production when Caveh took an additional job of teaching a documentary production class at the San Francisco Art Institute.

Since Caveh required all the students to make a film he required himself to do the same. The original idea was for me to record every interaction he had with the students, an essay on education. I followed a strict set of vérité rules. I was so intent on being invisible that I never spoke to anyone in class. I even removed the red light on the camera so no one would know if or when I was shooting.

One week into the semester, the World Trade Center buildings were destroyed and the film went off into an entirely different direction. Caveh got into a heated debate with one of the students who was frustrated with a class exercise in which the individuals had to float around the room, finding the space between themselves. As the discord built, taking up all the class sessions, the student demanded I stop taping (I didn’t) and Caveh demanded the student leave class (he didn’t). Caveh always claimed the result was a telling allegory of the state of the world with Caveh as George Bush and the student as Osama Bin Laden. It could have been vice-versa. I don’t remember.

I actually logged and paper cut all of Classroom in a crazed fifteen-hour session in the freezing lower Haight Victorian where I lived for most of the Bush years. A stoned member of the Brian Jonestown Massacre sat close by throughout, carrying on a conversation with his dirty socks. Somehow, I have always believed The World is a Classroom to be an incredibly accurate chronicle of how we all went a little crazy in those troublesome days and weeks after everyone’s life changed forever.

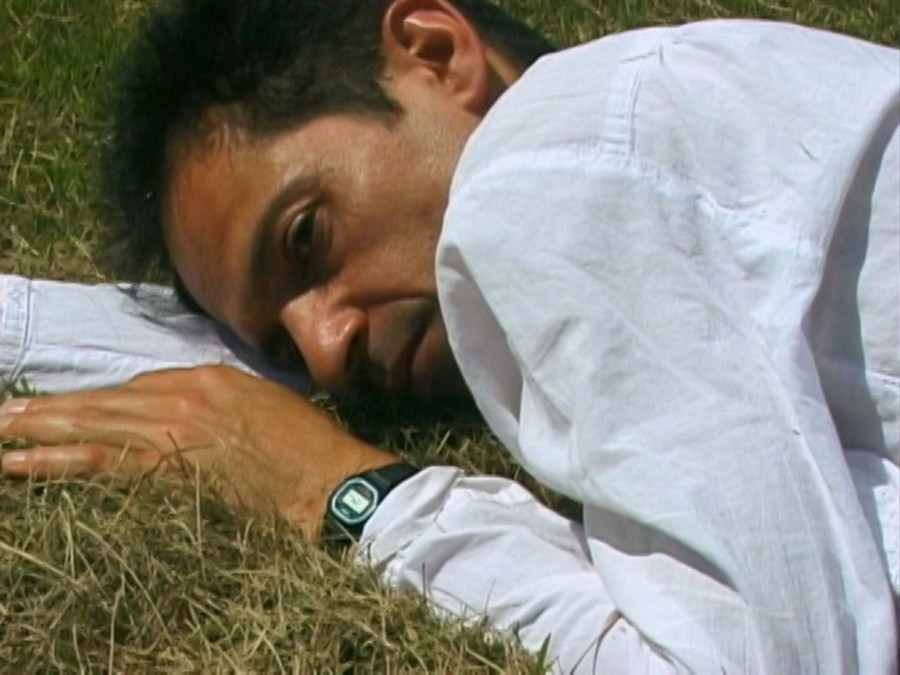

Several more mushroom trips were also recorded. One of these took place on a perfect summer afternoon in Golden Gate Park. Once again, I shot Caveh writhing and screaming, wearing a pair of striped pajamas and so incredibly thin that it looked like a concentration camp inmate had been given a day pass to the Japanese Tea Garden. What was truly strange was that we barely got a cursory glance from passersby. This was San Francisco after all. The trip came to an abrupt end after a nearby little league team lobbed a baseball into a beehive and everyone had to run for their lives.

As Sex Addict rounded the fourth year mark, Caveh’s obsessive perfectionism became positively diabolical. It took two recording studios and a staggering number of takes for him to get a satisfying reading of three lines of voice-over. It says much about how my work mode adapted to Caveh’s as I actually began to discern subtle differences in each endless permutation of the words, “Is she the one? Is she the one? Or is she the one?” It was the even-tempered Greg who, driving back with me one night from yet another re-shoot, wondered if perhaps Caveh had traded his sex addiction for the addiction of making a movie about his sex addiction.

The last months of I Am a Sex Addict were an exhausting period of last-minute shooting and mixing. On one particularly hectic day, I discovered I had left my cell phone in a taxi. One long train ride later to the dispatch office and a search through the lost and found turned up nothing. On the way back, I realized I had left my book bag with script and mix notes back at the taxi office. Returning there, I discovered my bag had been dumped into the trash. I ended up fishing around a row of dumpsters, one of those low ebbs where you begin to question the depressing circumstances that have brought you to this very moment.

Not finding my bag, I arrived late at Caveh’s, and he proceeded to chew me out for my tardiness. I snapped. Ugly words were exchanged and though we patched things up, it was never the same. We haven’t worked together since.

I remember a San Francisco test screening of I Am a Sex Addict at the Roxie on 16th street. During the lengthy scene in which Caveh gets a Korean masseuse to give him oral sex on her knees, I saw the shadow of a half dozen audience members rising and walking out. It suddenly occurred to me: they were offended. I had watched so many takes and worked so many hours on the scene that I had become immune to what was happening on-screen.

I realize how thoroughly odd my life had become because, right before people began exiting, a completely different thought had crossed my mind. We had forgotten to add a sound effect of the masseuse’s head hitting the wall, a change we were able to add for the Italian release of the film.

Some people go on about his radical cinematic honesty, rigorous work ethic or his ability to get to the essential but, most of all, Caveh Zahedi gave me a unique way to look at the world. Mushroom trips, personal video diaries and revealing (and sometimes even reenacting) the most intimate, embarrassing moments in your life became part of the daily routine. A seven-year routine during which I earned a living and began my career as a filmmaker, not just a very dedicated moviegoer. I am grateful to have been part of this time.

I hope the films of Caveh Zahedi will one day receive the recognition they deserve.

A shorter version of this article appears in Caveh Zahedi’s box set, Digging My Own Grave. The complete Caveh Zahedi box set is available from Factory 25: factorytwentyfive.com/caveh/.