‘Do you like gossip? Does gossip about dead people interest you? How about gossip about people who are dead but at one time were famous? Then this is for you.’

—from notes from From the Journals of Jean Seberg that were not used in the final film.

‘The major and most interesting part of film history is gossip: who was almost in which film, which film would have gotten made if only so-and-so had been in it and especially who slept with whom. Film history is a very, very long gossip column.’

—From the Journals of Jean Seberg

In 1996 or so, I was invited to write an article about Jean Seberg or about my 1995 film, From the Journals of Jean Seberg, by Raymond Bellour, one of the editors of Trafic. Various other projects I was doing, or scripts I was writing, kept me from it. Before I started the Seberg film, I wrote pages and pages of notes about various subjects that I knew the film would deal with: Joan of Arc, Jane Fonda, Clint Eastwood. They were stream-of-consciousness maunderings that were way too long to use in the film once I started the actual editing. They were little mini-essays which had to be cut, abbreviated, and re-arranged if they were to be used as entries from Jean Seberg’s “journals.” For the article, I suggested using some of the unedited notes that worked their way into the script, dancing in and out, like a very perverse call and response to a barrage of film clips. I stalled and stalled and then it seemed so far away that there didn’t seem to be any point to it, especially since From the Journals of Jean Seberg has never been shown in France. With the publication of this book, it seemed like an ideal opportunity to finally get around to it. The “essays” are pretty much as they were written before I started editing the film, unedited and untouched, with very minor tweaking, I think that “Jean Seberg’s notes” are sufficiently different from the final film so as not to seem redundant. One section, about Godard and Gorin’s Letter to Jane, was not used in the film at all.

Notes on Jane

In Barbarella, Jane does the first striptease in outer space, captured for earthly mortals in Playboy. She plays the first intergalactic sex-kitten, having sex with all kinds of creatures and objects. Vadim parades her around in a variety of S&M costumes suggesting a wide variety of overlapping fetishes, for the delectation of a presumably drooling, all-male audience. It’s Perils of Pauline in outer space with each planet stop posing a new sexual danger which invariably turns into a delight for our indomitable Jane. Vadim, who made And God Created Woman, which made his then wife Brigitte Bardot a world-famous movie star almost overnight, clearly enjoyed displaying his wives’ and girlfriends’ charms to a mass audience, hoping, as spectators, that they will occupy the place he usually does. When Jane threw her hat into the ring as a serious actress, none of this was held against her. But it’s also true that she was recognized as a serious actress only after she played a hooker—combining the best of both worlds. Although she publicly apologized for championing the cause of North Vietnam, she never apologized for playing bimbos. How come Hanoi was held against her but when she became a feminist Barbarella wasn’t? I guess your politics are recognized as a function of the real world whereas movie roles are recognized as an economic necessity, a job like any other, that you have to take. Everyone has to pay the rent. Even movie stars.

In 1992, I finished my film, Rock Hudson’s Home Movies, which I called “a fictitious autobiography.” Hudson, back from the dead, played by an actor, is young once again, and comments on various aspects of his career and his closeted sexuality, and how and where the two intersected. At the time I transferred the footage from VHSs of Rock Hudson, I also transferred hours of material about the representation of art and artists in American films. I planned to make a clip-film about the way Hollywood claims to worship but actually reviles art and artists, often at the very same time. It was to be called Art Is Just a Guy’s Name, taken from a line of Rock Hudson’s in Magnificent Obsession, when he proudly declares his disinterest in all things artistic. “As far as I’m concerned,” he boasts, “Art is just a guy’s name.” I had collected an assortment of real gems including Joan Bennett in Scarlet Street ordering Edward G. Robinson, since he’s a painter, to paint her toenails. She drawls sardonically, in the way that only Bennett could, “They’ll be masterpieces!” And then there’s Deborah Kerr, in An Affair to Remember, playing an accident victim who will never walk again, chirping optimistically to Cary Grant—who had always wanted to be a painter—without a trace of irony, “If you can paint, I can walk!” In the original 1939 version of the film, Love Affair, also directed by Leo McCarey, when Irene Dunne says the same thing to Charles Boyer, Boyer does a double take and looks at her as if she’s kidding. I edited about fifteen minutes of the material, which I thought was interesting and fun and I realized that only about ten other people in the whole world would be interested in this examination of Hollywood’s deeply conflicted relationship to all things cultural. I decided, since so much more work was required to make the piece into the feature length work I envisioned, it wasn’t worth the trouble. I abandoned it.

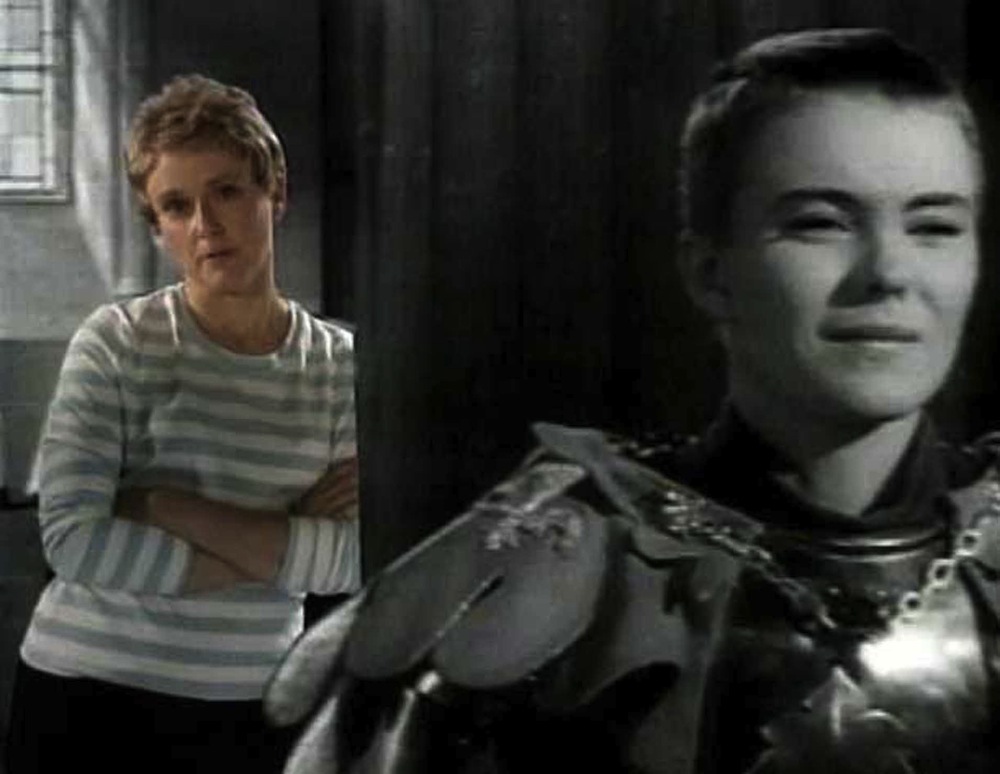

Around the same time, I read that Jodie Foster was planning to do a film about the life of Jean Seberg, with Foster herself playing Seberg. That really touched a nerve. I thought to myself, what the hell does she know about Seberg? To her, Seberg was just a historical anecdote, whereas Jean Seberg was a very important figure in my life at the movies. I was a child when Preminger announced that he was scouring the planet for an unknown actress to play Saint Joan. Even though I didn’t see the film when it was released, I remember very vividly all the hoopla surrounding that well-publicized search for a new face.

Breathless was released when I was a teenager and I didn’t quite get it (I thought that Hiroshima, Mon Amour, released the same year was a really important film whereas Breathless… What can I say? I was a very serious teenager). I certainly got Seberg and Belmondo although I was probably too young to connect with the film when I first saw it. Just because she studied French at Yale didn’t give Foster the right to lay claim to Seberg’s life. Seberg’s life and mine—as a viewer—intersected in too many ways for me to give her up without a battle. Maybe it’s not the best motivation for making a movie—a grudge fuck—but, hey, it worked. I was going to beat Foster at her own game and make my film first. And I did.

A filmmaker friend who had made a very well-received documentary that no one went to see had a great idea for me after he saw the film. In the ads for Jean Seberg, under the title, he said, it should proudly proclaim itself “An Essay.” Right. What do people go to even less than they go to documentaries? Essays. I didn’t take his generous advice. But I don’t think anyone was fooled, either.

Notes on Joan

Joan of Arc is to films what Macbeth is to the theater. It has a curse on it. Traditionally, everything goes wrong in any stage production of Macbeth. Even the play itself has to be referred to as “the Scottish play,” to ward off the curse, so that the gods will not pay attention to it. That’s why the play is so infrequently produced. As for Joan of Arc, nothing good happens to anyone who plays St. Joan in the movies. Falconetti, who played in Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc never acted in another film. She was so indelibly associated with the part that she consumed her own image in Dreyer’s film. At the outbreak of World War II, she emigrated to Buenos Aires. At one point, she went on a very strict diet that endangered her health. She was advised to see a doctor who wanted her to start eating again, but gradually. She went into a restaurant and ordered a dish of ravioli. And then another. She died of over-eating. Some say the raviolis were spoiled but in any case, she died. Her grandson, Gérard Falconetti, was one of the first people in France to have AIDS and committed suicide in 1984. And Ingrid Bergman? At the height of her popularity in America, after having played Joan of Arc on stage and on screen, had an affair with Roberto Rossellini. But this was while she was still married. She left her husband and infant daughter to live with Rossellini. Add to that that she became pregnant with Rossellini’s child while he was still married to another woman and before he and Bergman were married. These transgressions, after having played Joan and a nun in The Bells of St. Mary’s, ended her American career for almost a decade. She was vilified in the press, from the pulpit, and was virtually excommunicated from movie theaters in the U.S. Her second Joan was in Rossellini’s Joan at the Stake by Arthur Honegger, at the end of their relationship. It didn’t do either of them any good. It was the last of the five and a half films they did together during which time she didn’t do films with anyone else because he didn’t want her to. I wonder if she ever regretted not having appeared in Visconti’s Senso opposite Marlon Brando. What a movie that might have been.

The curse of Joan of Arc extends even beyond the actress who plays her on the screen. A sub-category should be added—actresses who play Joan of Arc in the movie within the movie that they’re in. Lucia Bosè, in Antonioni’s La signora senza camelie, in a role originally intended for Gina Lollobrigida, plays a former shopgirl who, because of her looks, makes it big as a movie glamour queen of the sex and sandal variety. She lets her husband talk her into making an art film as bid for artistic respectability—the life of Joan of Arc—which effectively ends their marriage and her career. She returns to the screen chastened and wiser, in another sword and sandal epic, which is where she really belongs. Alida Valli (also know as just plain Valli, when she was being groomed for glamorous Garbo-like roles) in The Miracle of the Bells, plays an aspiring actress who lands the role of Joan of Arc. Even though she is great in it, she dies before the movie is released. The producer refuses to release a movie, which could make a posthumous star of the actress but most likely won’t. Her death is bad omen and it’s bad for box office. Who wants to see a dead would-be star? It takes the miracle of the title to make him change his mind. The point is, playing Joan is bad for your health.

And, of course, there’s my story, I who had everything in the world—the most coveted screen role a girl could hope for, instant fame and success and then, a year later, international flopdom, failing very publicly when the movie was released. I was burned at the stake again when the reviews came out. Then I made my way back and, I suppose, I lived my life like most people, with the usual highs and lows—until I was thirty, when the lows took over. The curse of Joan took over and didn’t end until I committed suicide ten years later. Do me a favor, don’t invite me to be the guest speaker at any Joan of Arc film festival.

I was on the check out line at the grocery, if you can call a high-priced, snobby food store a grocery. A woman ahead of me on line said that after seeing the film, she got herself a Jean Seberg haircut. Someone I’ve been friends with told me the same thing. I didn’t think about it much but I guess it was flattering, although it really had nothing to do with me.

I had just finished editing and writing the video rough cut. All the spaces where the actress was to appear were just black leader, with my voice standing in for what would be the actress’ voice. Before this version was completed, it was almost useless to try to look for an actress—because there would be nothing to show her. There was an actress in experimental theater whom I had seen a few years earlier who actually did look like Jean Seberg. And she was wonderful in the material that she and her partner had written. Through a friend, I was able to track her down, where she was living in London. For a year and a half I had been dreaming of this actress as my ideal Jean Seberg. She came back to America briefly, because her mother was ill, and we met. Even though she looked the part, as a Jean Seberg who had gained weight and aged somewhat, I knew from the first lines out of her mouth that it wouldn’t work. Everything she said seemed flat and dull, the way it is when the wrong actor is reading your material.

My casting director kept promising me people but she never arranged for meetings. I did meet one young actress who has subsequently become a little well-known (maybe by the time this is printed, she will be even more well-known) and I realized the film would not be nearly as effective with a young actress. I wanted an older actress, someone who continued the aging process after Seberg died. It would, I felt, add a poignancy and piquancy to what she was saying. To have a young woman muse about various disasters in her life, disasters that still loomed ahead of her, didn’t make a lot of sense. It was less than four weeks from the time I had to shoot—the unfinished film had been invited to a film festival and I had a very tight deadline—and there was a great deal of script for the actress to memorize. Strangely enough, I wasn’t the least bit anxious about finding someone, even though there was so little time.

Anyway, after I finished the rough cut, I went out and, in a celebratory mood, bought a box of cookies. Even though I’m not supposed to eat things like that (is anyone, over the age of twenty?), I wolfed down the whole box of cookies. As I knew it would—as someone who has hypoglycemia and tries, if not always successfully, to stay away from sweets—it made me drowsy and I wanted to take a nap. When I woke up, the first thing I did was rush over to a film reference book and look up Mary Beth Hurt. Either in a dream or upon waking, her name came to me and I thought she would be the perfect person to play an older Jean Seberg. The only reason I tell this story is not to suggest that sweets, although they may be bad for you can also have good side effects, or that the best casting ideas come when you’re unconscious but something else. In the reference book it said that Mary Beth Hurt was born in Marshalltown, Iowa—the same city where Jean Seberg was born. Bingo! I was positive that she was going to do it. It turned out that Seberg had baby sat Hurt and Hurt remembered going to the parade welcoming Seberg back for the screening of Saint Joan in Marshalltown.

At the Toronto Film Festival, when I told this story after the screening, I remember Atom Egoyan asking during the Q&A what kind of cookies I bought. It was Hit cookies. I never bought them again. Nor have I subsequently tried to get a jolt of inspiration that otherwise eluded me from a sugar high. In any case, that kind of luck or chance or synchronicity or whatever you want to call it can’t be looked for, hoped for or asked for. It happens or it doesn’t. You don’t go after it. It will come after you. When I think about it, I don’t know what I would have done if Mary Beth Hurt hadn’t agreed to play the part.

Notes on Jean-Luc, Jane and Jean

What else did I have in common with Jane Fonda, aside from the fact that I jokingly called myself the poor man’s Jane Fonda? We were both in movies by Godard. But nobody deserved what he did to her after she was in Tout va Bien. No one. After the film, she went to Vietnam and was photographed with North Vietnamese peasants. The photograph made the front page of every newspaper in the world. “Star Consorts With Communist Guerillas!” And, of course, the way it was reported, Jane, not the Vietnamese war was the event. Godard couldn’t forgive her for that. But instead of talking about how her trip, just like any other event becomes, by its very nature, grist for the media, he excoriates her as if it were her doing—as if she were waging the war on North Vietnam, as if she had taken the picture with her tragic-looking face in perfect focus in the foreground, and the peasants blurred and relegated to the background, as if she had personally written the captions in every newspaper and magazine. He, along with Jean-Pierre Gorin, drafted his poison pen Letter to Jane. She, not the photographers or the merchandisers of the photograph, became the villain. Nor could he forgive the fact that she was rich, a celebrity, a movie star and especially a woman. Don’t tell me he would have done a similar hatchet job on a man. I don’t believe it for a second. This, after all, was the man who wanted me to rifle through Belmondo’s pockets as he lay dying on the street. Her real crime, in addition to the other offences was that she was a bleeding-heart liberal, not a Marxist-Leninist, and totally unschooled in radical rhetoric. The common perception is that actors are dolts, unable to think for themselves if they don’t have their lines written out for them. Well, after seeing Jane on TV defending her trip to Hanoi, I’m not sure I disagreed. But she got better at it the more she did it. And, I guess, that’s the point. When you become involved and discuss the issues a lot, you do get better at it. But at that time anyone could lay an elephant trap for her. I mean, after all, Godard wanted her in Tout va Bien because she was an American movie star. Then trashing her and publicly humiliating her in that poison pen Letter to Jane was like calling a woman you’ve slept with a whore because she had the bad judgment to sleep with you. I maintain that he would never have done anything remotely similar to male star. There’s always a sexual aspect to these so-called political vendettas. For example what the FBI did to me because I had slept with black men.

My worst fear was that Godard would do the same number on me in relation to my involvement with the Panthers. But I guess, as a French intellectual, the Panthers didn’t mean that much to him. In fact, the French found the Panthers sexy. Genet certainly did. And Vietnam was always an open wound with the French. After all, they lost it first. Then we went in and lost it again, under a new name. But they could afford to be self-righteous about it. Our atrocities were world class news, theirs were merely a continuation and an extension of 19th-century colonialist policies. Perhaps they would have done better to be more outspoken about problems in their own backyard—Algeria, for example.

I was afraid Godard would crucify me. But it never happened. I guess, unlike Jane, I was small potatoes.

A couple of film critics mentioned that I neglected to cite Letter to Jane. I thought the film too obscure to refer to and would be a diversionary little side trip that would not be interesting to a larger audience. Also, I didn’t want to have to deal with Letter to Jane, a film I find really hateful, over and over again in the editing room.

In David Richards’ 1981 biography of Jean Seberg, Played Out (I think it was one of the first hardcover books I bought), he mentions Seberg’s first serious boyfriend, a young actor from Texas whom she met in summer stock. They played in William Inge’s “Picnic” together and fell in love. The guy’s name was John Maddox. Now, years ago, in the late sixties I had a job on a documentary about killer sharks. This was way before Jaws. I was the sound editor and because the editing team was working on the film by day, I had to come in at night and add the glug-glug-glug to every breath that anyone took underwater. I found the job excruciating. I would transfer sounds from the master tapes to 35mm and lay them in. For amusement, I would poke around in the office refrigerator and nibble at the food. Usually, I was out of there by 11 o’clock, several hours shy of the time I was supposed to knock off. The point of the story is that the editor of the film was a John Maddox who came from Texas. He was a handsome guy and very quiet with a pleasant gravelly tenor speaking-voice with a trace of a Texas accent. But with a quietness that also suggested a roiling rage underneath. I sensed he was very unhappy and that he felt he was destined for more interesting things in life than cutting banal nature documentaries. It was almost physical—the unarticulated aching for something else that he radiated. In reality, I didn’t know very much about him, except that he loved The Beatles and that he always had very beautiful girlfriends. I met his girlfriend at the time who was a British beauty and may have been a model. She may even have been his wife. I can’t remember. He certainly never mentioned Jean Seberg. How do I know that this was the same John Maddox? My John Maddox, several years later, without having had any previous sailing experience, decided to sail by himself down the North Atlantic coast— in the middle of the winter!—all the way to the Caribbean. He was never heard from again. When the book mentions that Seberg’s Maddox was lost in the Bermuda Triangle I knew it was in fact the same person. But I learned something else as well—how an act that, even at that time, I thought was a terrible suicidal impulse dressing itself up as desperate macho posturing, can be seen as something adventurous and even romantic. To say that he disappeared in the Bermuda Triangle is a bit of fanciful eyewash that biographers and readers of gossip columns are so enamoured of. The truth or, rather, another truth, the one that I was familiar with, is much uglier but more to the point. But maybe I’m being harsher and more ungenerous than John deserved. Or is this the kind of situation in which one can genuinely say, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend”? In any case, this is how rumors and tall tales and even myths are born. Poor John. Poor Jean. If only they both could have remained young and in love forever…

Notes on “Lilith” and Women and Depression

You know, I’ve never believed those statistics that women are more depressed than men. It’s partly the way they measure depression and the expression of depression. If a man drinks too much and totals his car and takes a couple of people with him in the ensuing wreck, that’s called… well, what is it called? Drunk driving? Anti-social behavior? It’s never called manslaughter or, heaven forbid, suicide. If a guy is on a bell tower with a high-powered rifle, picking off people at random, he’s not depressed. He’s just…what? A psychopath, a sociopath? A loner, a loser. But he evades detection and the classification of depression. Women who have prescriptions for valium, however, never do. Women need “mother’s little helpers,” men need guns and bullets. I don’t believe the statistics for a minute. You, a woman, walks into the doctor’s office and whatever your ailment, if it can’t be seen, cut off, or cut out, they describe it as psychosomatic. I’d like a recount, if you don’t mind. And then there are all those movies about crazy women. All made by men, of course. The Blanche Dubois Syndrome. I played my fair share of them and that was good for me, as an actress. It’s always more fun to play someone off the deep end. But how come it’s always women who’ve gone over the edge? Natalie Wood in Splendor in the Grass, Catherine Deneuve in Repulsion. And Robert Altman’s Images with Susannah York. We’re living in her fantasy world as if any of these guys knew what a woman’s fantasy world was like. Me playing Lilith. Me in Dead of Summer, in which I play a woman who wanders around in a trance for the whole movie, wondering where her husband is and then, at the end, it turns out I killed him. Anyone ever see Schönberg’s “Erwartung”? Women, in case you haven’t noticed, only go crazy over love and aging. Men, in movies, anyway, don’t go crazy. They just want more—power, money, guns, whatever.

Actors can’t afford to question the ideology, the meaning, the ultimate what-is-it all-about? of the script. If they did, would they ever be able to act in anything? Too many questions or objections and you would never be able to say yes to anything. You’d be playing Hamlet in your own castle in Denmark. No, when you read a script, you have to wear horse blinders. You read it to see if there’s anything there for you, if there’s anything you feel you can do with the lines on the page. Salary of course is not an inconsiderable consideration. I’ve played the whore more than once. I had a family to support—a child and a nanny, lawyers, agents, accountants. Everyone has to be paid. And sometime you work just to pay them. And then there’s your summer house as well. That had to be paid for, too. Movie stars are no different from other people. They have to eat, too. OK. I played those parts. They were offered to me. I took them. Isn’t that what actors do? That’s what I did.

An arts journalist camouflaged in floppy hat and sunglasses told me after a press screening that she had auditioned for the role of Saint Joan but I shouldn’t tell anyone else. She didn’t share this confidence with the people she worked with because then they would know how old she was. She had no memories of her audition.

My then wife and I were both fans of Jean Seberg. Before she and I met, independently of each other we both saw and fell in love with The Five Day Lover, a bittersweet Mozartian comedy with an ending so sad and unnerving it feels like a punch in the guts. And neither of us went to see it because Phillippe de Broca directed it, either. Somewhere around the time that I was working with Maddox, my wife and I went to see Dead of Summer on 57th Street at a theater that is no longer there. We went together to see