In Richard Gordon’s puppet horror Devil Doll (1964), a smarmy, goateed showman enters London to unveil his act: a mixed ventriloquist/hypnotist show. Vorelli’s mesmerism leans on predictably exploitive gags (“When I snap my fingers you’ll dance a strip tease!”) but his real audience lure is Hugo, a grossly childlike wooden doll that likes to step off Vorelli’s lap and walk, without aid, towards the marveling crowd. And when that crowd applauds, neither the puppet, the master, nor the adulators know for whom they clap.

In private, Vorelli insults Hugo loudly, asserting his control with projected self-loathing. “You are a dummy, Hugo,” becomes a refrain that’s less obvious every time it’s stated. Precisely why should a ventriloquist need to remind his dummy that he’s inanimate? Or is it the dummy he’s reminding? Like Dr. Mabuse before him, Vorelli pulls strings that are invisible at a distance and only slightly clearer in proximity. If idle hands are the devil’s workshop, what are puppets?

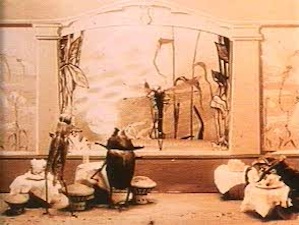

You can find a literal answer in Jan Svankmayer’s Don Juan (1969). Svankmayer’s “ladykiller” is an actual murderer. Juan solves his social problems by killing the people he considers obstacles, and he begins with his father. His dull sword and small rock hack at his dad’s face chipping paint cracking wood with such inefficiency you think it’ll never end. It’s horrifying because the bloodless injuries make it impossible to see the life force you believe is leaving the character. And though all you just saw was inarticulate whittling, you have the feeling of a life lost, an atrocity witnessed. It’s just as horrifying as any Saw movie, but more stunning because once you see what that character was made of—actually made of—this entire puppet proposition makes much less sense.

Puppets are as much a fixture of horror as children’s stories. E.T.A. Hoffman’s Sandman was manipulated by a doll maker to pluck the eyes from sleepless, disobedient children.f The creepy dance of death and reanimation is an undercurrent for most puppets on film—less so than in theater where ventriloquists and puppeteers are more self-conscious and their relationships with their puppets are more physically apparent. On film, stop motion can lend puppets an off-putting gravitas. Everything they do is concrete, literal, real, but what it signifies is almost always ephemeral, theoretical, existential.

Yet they’re so explicit they seem inoffensive. How aren’t they toys just demonstrating their interior life? All children are already in on that secret, which is perhaps why we think puppets make sense to kids, or at least speak a language kids can access and we can observe. The Quays may be creepy and the Czechs maybe theoretical (or just gory) but among even the creepy and the gory there are highly sophisticated, kid-appropriate films that provide glimpses into a world unseen and still somehow still familiar. Jiri Barta’s The Pied Piper of Hamelin (1986) may be heady and haunting, but what parents take as a treatise on the importance of paying for pest control, kids see as a story about filth and greed. In that light it’s possible the communist undertones may read better to seven-year-olds, even if those seven-year-olds are not proficient in Marx. Regardless, we’re not all watching the same thing.

It’s not always eerie. British puppeteer Gerry Anderson, the guy Matt Stone and Trey Parker lampooned with Team America: World Police, only seemed to make goofy, sci-fi puppet-toons. His show Thunderbirds was pretty kid-centric and Anderson never seemed ashamed of his audience or his budget. Sometimes, the corners of his set were visible and the strings that carried his aircraft showed through, but for kid fare this was charmingly homespun. Kids sleep with stuffed animals and name them and give them private lives: if anyone can be called upon to overlook the limitations of their loved ones (polyester fur, plastic eyes, stuffing) it’s a kid. So when a genre demands that we see a janky macquette, plaster head or a shoe, and believe it’s a character with desires and motives, we may have to call on our more childlike, or more primitive instincts.

Primitive is such a charming word, isn’t it? It immediately suggests the person using it has a “modern” perspective, so the word always carries the connotation of naiveté. They call primitive cinema “pure,” and if a film flies under this banner, it often feels as unknowingly produced of wickedness as babies. With puppets, whatever evil gives them “life” is somehow implied by their ramshackle movements: the junkier they are the more nefarious the spark that animates them.

The creepy dance of death and reanimation is an undercurrent for most puppets on film—less so than in theater, where ventriloquists and puppeteers are more self-conscious and their relationships with their puppets are more physically apparent. On film, stop motion can lend puppets an off-putting gravitas. Everything they do is concrete, literal, real, but what it signifies is almost always ephemeral, theoretical, existential.

Ladislas Starevitch animated a cast of dead beetles and roaches for The Cameraman’s Revenge (1912), and they catch each other “in the act” of fornication, adultery, peeping, and then projecting illegally obtained content of fornication, adultery and peeping. If the kids ask questions consider the blanket explanation: “They’re fighting.” (Entertainment law is tricky.) For all the grossness of watching bugs wrestle, Starevitch’s bottom feeders are oddly unthreatening. The Quay Brothers’ beetles look dangerous and Jan Svankmayer’s beetles evoke Kafka and scramble everywhere. Though the bugs are technically taxidermy, they look like toys and imply a license to treat them as such…just don’t forget to wash your hands after.

Emile Cohl, the French “father of the cartoon,” gave two pairs of footwear romantic inclination in Matrimonial Shoes (1909). Left outside for a shining, they entwine, nuzzle, and make sweet, sweet leather together. Their owners get in on the romance, naturally. And this is one of many cases of an “inanimate” object paving the way for its human counterpart. Yet for Cohl, his inanimate objects typically didn’t require human agency.

The Automatic Movie Company (1911), which Cohl reportedly produced with Romeo Bosetti (1911) was an imitation of his earlier Pathe film Mobilier Fidele (1910). It begins with a floating letter announcing a move. The house (rather than its keepers) knows it must be emptied of its contents, and so the furnishings magically relocate. Plates fall and dustpans and brooms promptly clean the mess. It’s as much a fantasy for children as adults (if not more so for adults).

Cohl’s Boutdebois Brothers (1908) animates toys in an adventure on the flying trapeze. Monsieur Clown Among the Liliputians (1909) is also a circus comedy but this time the animals enlisted in the show can’t seem to obey their Clown Emcee. Let’s Be Sporty (1909) is a test of Cohl’s charm and a template for how different kinds of movement (driving, boating, walking, skating, swimming) look on film.

It’s not until The Magic Hoop (1908) that Cohl seems to touch on the nameless creative spark that animates the inanimate. A little girl pushes her hoop around until a man shows her it can be used to change his identity, her costume and the world around them both. It’s an enchanted perspective device and when hung on the wall, the hoop continues its magic, bringing visions of moon cycles, sunsets and morphing creatures. The Little Soldier Who Became A God (1908) marches out of sardine can with his squadron and through a roughly drawn world. When one tin soldier finds himself away from his troop, he mystically appears among a tribe of natives who declare him a god. The sense of invention is evocative of early Looney Tunes: do you remember mice in matchbox beds? Spool of thread for a nightstand? Handkerchief for a bed sheet? These worlds are like Chaplin with even less regard for convention.

‘Hugo Is a Dummy….’ Part 2 and Part 3: Coming soon.