“What an awful day,” my husband said. I was surprised: There’d been no screaming, no long conversations about suicide, no fits of rage that day. Stupidly I replied, “Huh, what was so awful about it?” “I woke up today,” he answered, adding, on his way back to bed, “Sometimes I feel like we’re not even in the same room.” My husband has bipolar disorder. I love him more than I’ll ever be able to say, but he’s not the easiest person to live with. And he loves me, but I’m not a part of his brain like it is. That curt sendoff is the best way he’s ever described our relationship with the disorder. There are three beings in our marriage: my husband, his mental illness, and me. And sometimes we’re not even in the same room.

I’m not a doctor, or an expert, but I explain it like this: Once referred to as manic depression, bipolar disorder is a mental illness that involves powerful, unpredictable mood swings, which can last anywhere from days to months at a time. Folks with bipolar experience the highest of the highs and the lowest of the lows. Having the disorder, or loving someone who does, is about learning to live with failure. You spend half the year enthusiastically writing bad checks, and the other half hiding in bed because you can’t stop crying. Somehow though, amidst the medication-juggling and the suicidal ideation, you’ve got to rebuild on the ruins of whatever remains. Most of the time it’s not a lot.

In the recent rocky years of our marriage, my husband and I both have become familiar with the different ways bipolar disorder is presented on screen. (Suffice to say it’s fitting that the earliest movies depicting mental illness—The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, M, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—were horror movies.) I’ve found a lot of solace in the fairy tale that is Silver Linings Playbook (2012). I must have watched it ten times because it was so nice to see a happy ending on a bipolar story. Too bad it’s bogus. Silver Linings Playbook begins with the rebuilding process. Bradley Cooper’s character has just gotten out of a mental institution after having a major nervous breakdown. He’s on the up and up, manic and more manic, building and rebuilding the life he once had. The movie exists entirely in his manic phase, without ever showing the depressive side. He’s either waking his parents up in the middle of the night to have an intellectual conversation about Hemingway, or acting like a manic pixie dream guy, some charmingly anti-social sitcom character whose inappropriate observations could easily be accompanied by a laugh track—instead of the blank stares and fractured social life that I’m often witness to.

Sure, Cooper’s character slips once in a while, but we’re offered no true sense of his ruins, of the ground zero of his existence. Silver Linings Playbook is a movie about success, the illusion of a cure. But mental illness can only be managed. There is no escape—not love, not family, not success. Only death. I’ve read that David O. Russell made Silver Linings Playbook because his son has bipolar disorder. Maybe he wanted the film to chart an optimistic course. That’s understandable, but it’s not a world that’s familiar to me.

Most modern movies about bipolar aren’t very familiar to me, actually, because they’re essentially lesser versions of Silver Linings Playbook. Many of them—Mad Love (1995), Infinitely Polar Bear (2014), Touched with Fire (2015)—romanticize the illness to a point that’s almost harmful. They often play up their characters’ mania, because that’s the “fun” part of the disorder. It’s “fun” to watch Mark Ruffalo act kooky, chain smoke and lovingly scream at his daughters, just like it’s “fun” to watch Katie Holmes and Luke Kirby go off their meds and imagine they’re in Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night and be oh-so wild and creative and carefree! In the same way Scorsese films “critique” their flashy gangsters and criminals, most movies about bipolar wind up making the illness look attractive because they don’t honestly show what it’s like to cycle between the ups and downs—and deal with the damage you accrue in between.

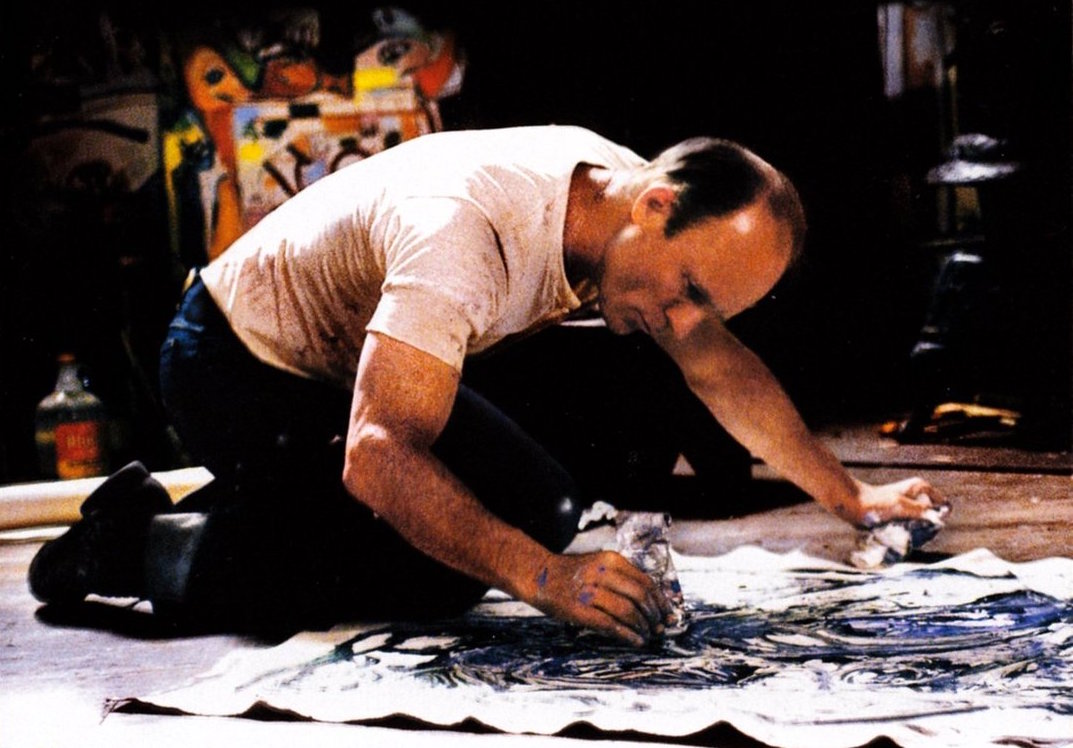

The world of Ed Harris’s vastly underrated Pollock (2000) is nothing but damage. It’s also one of the few movies about bipolar disorder that’s depicted from the perspective of the sufferer, as opposed to the witnesses. Lust for Life (1956) and Mr. Jones (1993) are two others, but both of those films, good portrayals though they are, follow the Silver Linings Playbook route by adding unjustifiably happy (or happyish) endings.

Mr. Jones accurately shows both the mania and the depression. The title character, played by Richard Gere, withdraws $12,000 from his bank account and blows it all in one day on a huge shopping spree before getting arrested for interrupting a symphony performance; shortly thereafter, he’s so depressed he can hardly talk. Still, the movie ends with reassurance: Mr. Jones will be OK because the psychiatrist he’s in love with, played by Lena Olin, quit her job to be with and take care of him. That’s one of the other lies these movies often tell: that love is all you need to “cure” the mental illness.

Lust for Life betrays Van Gogh’s life and, really, his immense suffering, by trying to justify everything he went through—the pain, anguish, confusion, all of it—as necessary for the reward of posthumous success. The beginning lists some of the museums and famous people who own his paintings. The ending displays many of the paintings together on a gallery wall, a glorious collage of color and madness. In between, there is serious misery, but the film’s structural sandwiching of Van Gogh’s life implies that the torture he lived with for thirty-seven years had merit because he finally was validated by capitalism and the art world. As portrayed by Kirk Douglas here, he’s the ultimate misunderstood genius, the romanticized madman.

Artists’ lives seem to lend themselves well to this kind of characterization, but it’s worthwhile to diminish the myth of an inherent relationship between art-making and mental illness. There are no more mentally ill artists than plumbers; it’s just that the artists, the successful ones, leave a sexy trace for us to follow. In reality, the rich people who own Van Gogh’s paintings wouldn’t have had anything to do with him. Like most people during his lifetime, they would have been disgusted by his dramatically uncouth manners, and by the dirt under the fingernails of his trembling hands.

Pollock doesn’t shy away from the unpleasant. Nor does it sugarcoat the mental horrors of the artist’s life by validating him and his work through artistic success. Harris’ Jackson Pollock is suffering, and he’s just as lost in his fame and fortune as in any other place. The movie opens with Pollock signing copies of his Life magazine article—exposure he thought he wanted, but has discovered to be meaningless. It doesn’t make him happy because he can’t be happy. He feels the same horrors whether he’s wining and dining with Peggy Guggenheim or drunkenly passed out in the gutter with piss stains all over his pants. Harris gets what it’s like to be in a room with a manic, rage-filled person whose emotions skyrocket from zero to 120 in a half-second. How nerve-wracking it is to be around a person who flips over dinner tables and screams in your face on a regular basis. The point of Pollock isn’t that he’s a mad genius, it’s that he’s damaged. You don’t leave Pollock thinking about the beautiful art he made; you leave it feeling crummy and sad for this sad and crummy person.

Most movies about mental illness reaffirm societal notions about how burdensome it is to people who don’t have it. For example, this year’s lovely A Light Beneath Their Feet, starring Taryn Manning and Madison Davenport, gives an honest, insightful look into what it’s like to live up close and personal with someone who has bipolar disorder. Manning and Davenport play an inseparable mother and daughter constantly battling the everyday realities of the mother’s illness, from getting her to take her medication to hold down a job. Manning’s character is very attached to her daughter, who has her choice of college but also wants her to stay close by as a caregiver. Naturally, the girl feels stifled by her mother’s illness and clinginess and wants more than anything to just get away and be a “normal” person. A Light Beneath Their Feet goes to great lengths to show that maintaining a good relationship with someone who’s mentally ill is possible, if hardly easy, with mutual honesty and openness.

And of course, everything is harder for women. Though no one in the movie ever says so explicitly, it’s fairly clear that Gena Rowlands’ character has a variant of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in A Woman Under the Influence (1974). Like Splendor in the Grass (1961) before it, A Woman Under the Influence shows the painful reality of what it means to be a mentally ill woman, and the hysteria we’re often driven to when we don’t fit into society’s nicely designed roles for us. Both of these films are agonizing to watch because of how the women are degraded by the people around them. Too often it seems that mentally ill men are more socially tolerated than mentally ill women—that it’s acceptable for men to be extreme, gregarious, and inappropriately candid, particularly with their mental illnesses. In Infinitely Polar Bear, for example, it’s more taboo for Mark Ruffalo’s character to be a stay-at-home dad than it is for him to be mentally ill. Were it switched around, with the mom, played by Zoe Saldana, as the bipolar one, it would basically be A Woman Under the Influence.

In that movie, Rowlands plays an innocent if an eccentric young mother with an often-absent husband, played by Peter Falk. She keeps her house clean, takes good care of her children, and always looks beautiful, but she’s a little twitchy, a little off. And also quite obviously very depressed, though no one pays her enough attention to notice. They just know she makes people uncomfortable because of her manic manners and peculiar charm. No, she doesn’t go around cutting off her ear or flipping over dinner tables, by any means; it’s challenging to figure out just how much of this persona owes to genuine mental illness and how much of is the result of the mental, emotional, and physical abuse she’s endured from her husband. Not only does he violently slap her, in two of cinema’s most distressing scenes, but he also constantly puts her down, and makes her feel guilty for being who she is. Anyone would go a little berserk in the same situation. Eventually, after she embarrasses him one time too many, he ships her off to a mental institution. He thinks his wife should be everything he, and only he, wants her to be. It’s hard enough to be mentally ill without being pressured to conform by the people who are supposed to love you.

As sad as it is to say, not much has changed since A Woman Under the Influence. Mentally ill people—even if they’re men—remain socially unacceptable and stigmatized. It’s often recommended in some mental-health forums not to disclose any of your issues to your employer, for fear of further mistreatment. And after being fired for an illness that has no cure, it’s almost impossible to find work again without keeping that part of your identity a secret. Work-life balance is hard enough when life balance alone is way out of whack.

We can’t fairly blame cinema for these societal ills, but the least we can do is call for a fairer, more complex representation than occurs in most of the movies I’ve called out here, among others of their ilk. If only to acknowledge that film can and should speak to the full range of human experience—and maybe, too, it can even answer the sad-faced questions I always receive when explaining my husband’s eccentric behavior to the unwoke.

Find Sara Freeman on Twitter, @CelluloidAngel.