[Editor’s note: The films in this article appear as part of the ‘Men in Peak Form’ theme on Fandor via the Criterion Collection for a limited time.]

Movies have always made more time for Love Gone Wrong than florists and greeting card companies, despite the tradition of the happy (or “Hollywood”) ending. An imploding relationship is a spectacle one can hardly help but stop and gawk at. It stirs sympathy, of course, as well as morbid fascination, the latter benefitting from schadenfreude: Such things may have happened to you before, but thank god, this time they are happening to someone else. Even better, someone fictive.

Two European classics in the Criterion Collection, both dating from the early 1950s, see romance going very awry despite protagonists whose passion burns bright. Unfortunately, that emotion can turn into light pollution when directed at an object that would rather be left in the shade, or shone upon by somebody else’s high beam.

Like Emma Bovary, Anna Karenina and other literary heroines of her mid/late-19th-century era, Countess Livia (Alida Valli) in Luchino Visconti’s 1954 Senso is a respectable lady trapped in a dull marriage she finds suffocating. She seeks to escape it in the arms of a lover, but that decision proves her undoing, in large part because the man she chooses (or vice versa) can’t/won’t return the full emotional investment she’s made, and which she’s willing to give up “everything” for.

A Venetian aristocrat in support of Italian nationalism (in contrast to her husband, a pragmatic opportunist) during a wartime period of Austrian occupation, Livia first meets handsome, dashing, callow Lt. Franz Mahler (Farley Granger of Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train) by accident. She’s disinclined to exchange more than passing civilities with an officer of the enemy army. But Mahler, bored and predatory, sniffs the vulnerability beneath her hauteur.

Once her resistance has been conquered, he quickly loses all interest. But Livia, perhaps an easier target for a seducer’s gamesmanship than a less privileged, sheltered woman would be, finds no amount of rejection or humiliation can quell the fire that now burns in her heart. Between her increasingly reckless behavior and his bottomless contempt, this can’t end well, particularly once she makes a decision that amounts to a betrayal of her most cherished ideals…all for a man who, far from grateful, cries “I’m not your romantic hero!”

Senso was Visconti’s fourth feature, but the first in his lush, “operatic” mature style after earlier films’ flirtation with neorealism. It remains a sumptuous experience, beautifully appointed and shot in Technicolor, with music by Bruckner and Verdi. But the gorgeous costumes and sweeping camera movements serve a story that, like most of this great Italian director’s later films (The Leopard, The Damned, Death in Venice etc.), ultimately makes a cruel mockery of any hoped-for romantic love. Liberally adapting Camillo Boito’s original novella to heighten its historical/political context, Visconti and co-scenarist Suso Cecchi D’Amico make Livia’s amour fou a disaster of national proportions. In the end, the mutual self-destruction she and Franz ensure for one another is an even stronger a force than the delusional love that brought it about.

The Orpheus myth, as it’s popularly understood, offers a much simpler take on love: Boy meets girl, boy marries girl, boy loses girl (she’s chased by a satyr into a nest of vipers…happens all the time), boy mourns so beautifully he gets permission to rescue her from the Underworld. But of course there’s a catch, in that Orpheus can’t look at Eurydice until they’ve both safely made it back to the “upper-world” of the living. When he jumps the gun, he loses her again, this time for keeps.

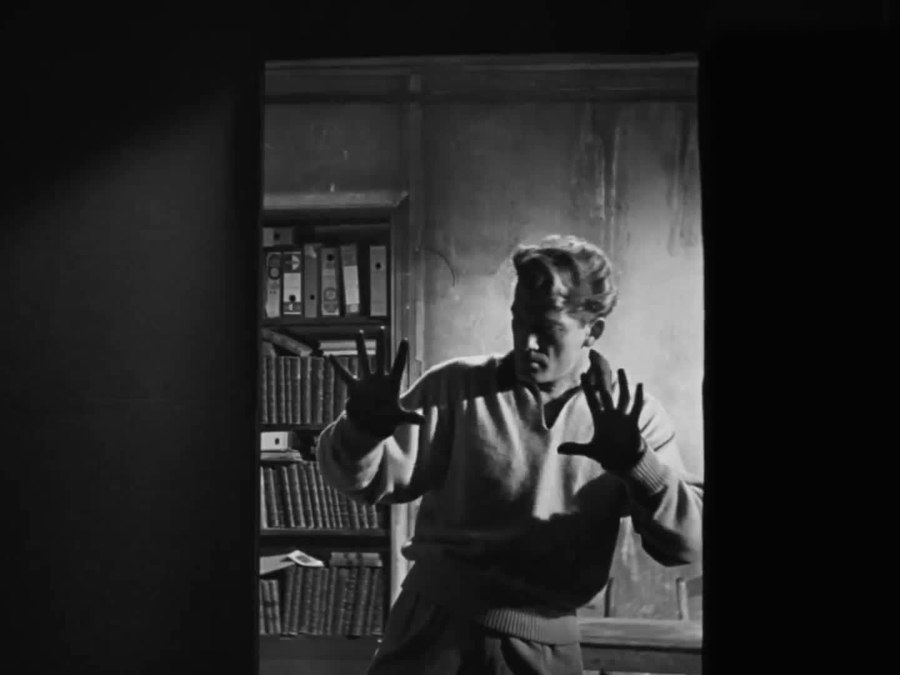

That Jean Cocteau’s 1950 feature updates this tale to modern-day France is the least of its liberties. Here, Orpheus (Jean Marais) is not a musician but a well-known poet envied by jealous, youthful talents. When one of the latter is killed in an apparent accident, witness Orpheus is swept into the orbit of the chic, imposing Princess (Maria Casares), also known as Death. She covets this creative mortal, with his chiseled features and blond pompadour, just as her assistant Heurtebise comes to covet Orpheus’ pregnant wife (Maria Dea).

As in the basic original tale, our protagonist must eventually descend into Underworld to rescue his wife. But this time his mission seems more driven by duty than devotion, as he’s caught up in a convoluted four-way chain of desire in which Eurydice is the sole participant whose love doesn’t cross a line between living and dead.

Orpheus was made by Cocteau, a man of many artistic hats, at a point when WWII and the Occupation were still very fresh in the collective memory. While his 1946 Beauty and the Beast (also starring personal muse Marais, as the latter) embraced romantic fantasy whole in a spirit of escape from wartime hardships, Orpheus leaves fairy-tale whimsy behind for a much thornier consideration of the gap between personal desire and the greater good. Even Death is no free operator here. She and her flunky are answerable to a rigidly bureaucratic “underground” tribunal whose harsh (but just) doling out of punishment for deviation from the rules feels very much like a thinly veiled portrait of the French Resistance.

For all the film’s transfixingly simple “magical” effects, it’s rooted in a matter-of-fact social order that can’t be transgressed, not even in the afterlife. There is scant fulfilled love in this Orpheus, only joyless, necessary sacrifice. This perverse anti-romanticism was present onscreen in more ways than most viewers at the time would grasp: Cocteau cast as the young, accident-slain poet an actor (Edouard Dermithe) who had recently replaced star Marais as his own offscreen innamorato. The cinematic language of Orpheus is full of enchantment. Yet far from offering any “happy ending,” the emotional content here underlines time and again that love can be as conditionally clause-ridden and buzz-killing as a legal contract.