That there are no less than ninety-nine film stills used to illustrate the thirty-three-page introduction to Hou Hsiao-hsien, the first English-language critical anthology published on the Taiwanese filmmaker, indicates just how “visual” the director’s style is. All films are definitionally “visual,” of course, but as is repeatedly argued in this insightful tome, Hou’s cinema seems to be exceptionally so: since making his debut feature Cute Girl in 1980, he has continued to consciously set new challenges for himself and his cinematographers, resulting in visually interpretable works of staggering image density and cinematographic depth. Collecting and editing a volume such as this is no easy task; to his credit, Richard I. Suchenski has amassed a body of essays from critics, academics and Hou’s collaborators that is as insightful about Taiwan as it is about the director’s working methods.

Hou is the kind of singular auteur whose works are distinct from one another at the same time as complementary: they are part of an ongoing aesthetic project whose overall aim is to reveal, examine and probe the many complexities and numerous traumas that have defined Taiwan’s modern history. As is argued here, Hou is Taiwan’s most Taiwanese filmmaker. His is a cinema, that is, of aesthetic flux and assimilation, of cultural openness and deep sensitivity—sensitivity to a country that has, for much of its history, been subjected to colonization and brutal suppression. With the Dutch, the Spanish, the Japanese and the Chinese all having ruled it, Taiwan is a hotchpotch of influences: its politics, its philosophies, its artistic traditions and national identity all have a long and complicated history.

For his part, Hou—born on mainland China in 1947 but brought up from 1948 in Taiwan—seems to have consciously worked towards an artistic understanding of such intricacies. Situating the filmmaker’s contribution to the local film scene within the context of a global festival circuit, Beijing-based academic and scriptwriter Ni Zhen here claims that Hou is a “filmmaker dedicated to merging different Asian cultures.” There’s more than a touch of European about him too: while his acute commitment to realism has evoked comparisons to Italian neo-realism (something one critic here claims the director has actively worked through rather than simply emulated), Hou himself has repeatedly expressed a debt to Godard, Bresson and Visconti.

Ozu is perhaps the most formidable name to whom Hou is repeatedly compared. But Suchenski—founder and director of the Center for Moving Image Art at Bard College, and the initiator of “Also Like Life,” the Hou retrospective currently traveling the world—has, like Hou himself, allowed for contradictions. While Ni, mentioned above, is correct to note Ozu’s influence on an explicit homage like Café Lumière (2003), Wen Tien-hsiang suggests such comparisons are facile: “The editing styles alone show the substantial difference between Ozu and Hou, so we can only say that both masters are very good at capturing the essence of daily life.”

Hou’s cinema seems especially open to premature categorizations. Though he began his career making commercial films, his contribution to his Taiwan’s New Cinema movement in the 1980s demonstrated not only an adaptability, but also a willingness to take things to an unprecedented level when it came to serious artistic renditions of his country’s recent and tragic past. Showing a gradual preference for longer-than-average takes, his general aesthetic style seems to have pre-empted the recent critical focus upon “slow cinema.” But, as Suchenski points out in his introduction, Hou has garnered an “exaggerated reputation as a minimalist—his is above all a cinema of movement.”

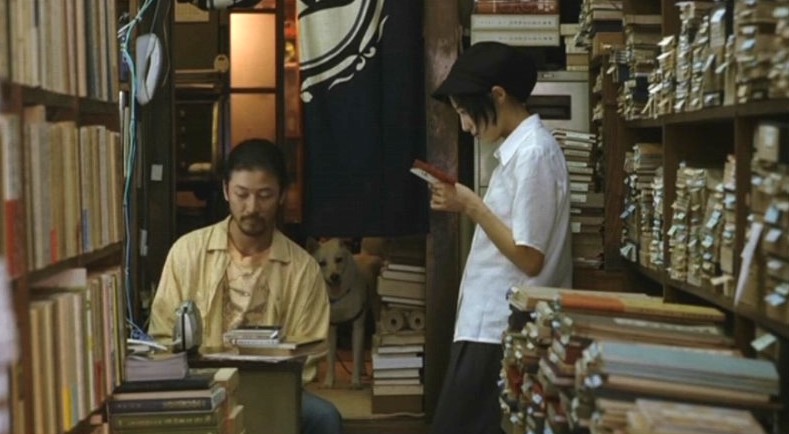

This much seems correct. Unlike too many other filmmakers who belong and sometimes consciously aspire to the ‘slow cinema’ label, Hou’s long takes and long- to medium-long shots never feel like a pretension. To begin with, the cluttered mise-en-scène and complex blocking strategies in films like A City of Sadness (1989) or Goodbye South, Goodbye (1996) evoke an organic, lived-in universe that even in a period film feels at the very least spontaneous and, at a stretch, documentarian. Hou’s is a cinema of movement, and every movement has a purpose.

Forgoing the go-to chronological template in favor of a progression through Hou’s thematic preoccupations, Suchenski’s book brings together a range of critical authorities. Though some of the translated texts feel overwritten, and are occasionally allowed to run uninterrupted by what would be helpful illustrations, their ordering is faultless. At first, the overall celebratory purpose appears to overwhelm the contributors. Hasumi Shigehiko, for instance, sets himself the task of investigating why Hou’s cinema is so “enchanting”—hardly a scholarly question. For all the intermittent risk of hyperbole, though, insights are frequent: Hasumi himself offers one of the book’s highlights with an extended analysis of Hou’s fondness of placing light sources directly into his films.

Such a focus on unusual but concrete details is always the life force of textual analysis. Hasumi’s chapter leads naturally into James Quandt’s discussion of lighting in Three Times (2005), while James Udden’s argument for why Dust in the Wind (1986) is the definitive New Cinema work is a welcome and persuasive diversion, before a more academic essay from Mark Abé Normes—whose otherwise fascinatingly detailed navigation of visually complex scenes containing calligraphic characters would have been helped by more illustrative stills; as is, such written analyses counterintuitively validate the growing use of video essays as a legitimate form of criticism.

As one of the few English-language writers contributing to this highly recommended primer on Hou, however, it is Kent Jones who compels the most. (His essay also doubles as an effective stepping-stone between more scholarly essays and contributions from the likes of Olivier Assayas, Jia Zhang-ke and Hirokazu Kore-eda.) Like the best critics, Jones can make the most analytical prose sound anecdotal, the most whimsical opinion hit like a hard rock to the face, and can shift between historical context and detailed specifics with the most delightfully cunning sleight-of-hand.

Opening with a discussion of a scene in Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959), Jones goes on to describe and analyze The Electric Princess Picture House, Hou’s three-minute contribution to the portmanteau film To Each His Own Cinema (2007), which was commissioned for the 60th Cannes Film Festival. I haven’t seen the film myself; Jones’s entry, down to its sublime concluding sentence, has pushed it to the top of my list.

Hou Hsiao-hsien (edited by Richard I. Suchenski. Vienna: Austrian Film Museum and New York: Columbia University Press, 2014. 272 pp., illus. $32.50 / €22.00.