You’d’ve been forgiven for mistaking the opening days of last fortnight’s big international film festival for a premature Cannes. On Tuesday the first week a who’s who of directors could be seen fawning from the front row of an Isabelle Huppert master class. On Wednesday the same crew flanked Catherine Deneuve, like so many attentive disciples, at a reception dinner following a gala screening of her On My Way. But the filmmakers in question included not just Wong Kar-wai, a May fest favorite, but also Johnnie To, Dante Lam, Peter Chan, and compatriots. And the festival program, in addition to events celebrating the 50th anniversary of Sino-French diplomatic relations, promised a Hong Kong Panorama, a Young Asian Cinema Competition, recent works by Asian “masters,” retrospectives of Japanese avant-gardist Matsumoto Toshio and controversial Mainland actor-director Jiang Wen, and sections of expertly curated Taiwanese Cinema and Filipino “Glories.” Outside the Grand Theater, not the pedestrian-friendly Croisette, but the terrorizing traffic of Nathan Road, the Tsim Sha Tsui docks of the aging, tar-soaked Star Ferry fleet, and an ass ton of dazzling skyscrapers. Hong Kong.

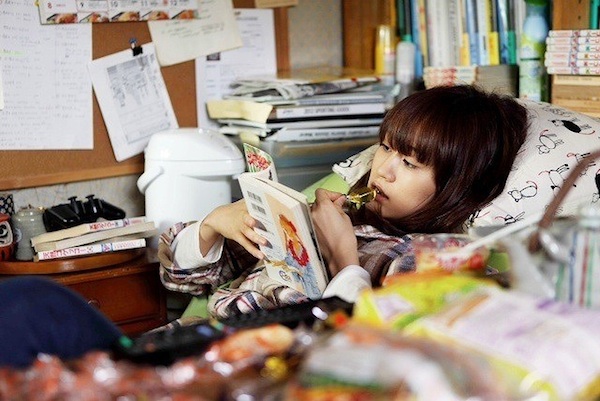

While Huppert and Deneuve entertained Wong & Co, veteran directors Yamashita Nobuhiro (Linda, Linda, Linda) and Aoyama Shinji (Eureka) attracted the HKIFF’s unusually youth-skewed audience with projects featuring J-poppers. In Yamashita’s perfectly paced seventy-five-minute Tamako in Moratorium AKB48 idol Maeda Atsuko plays a droopy college-grad who lounges around her pop’s sporting goods shop, no intention of hunting for a proper job, “at least not now”. Antics don’t ensue. Rather, Yamashita’s comedy is the kind in which a monk shops for a new putter, a slacker kid plays rock-paper-scissors with her parents to see who’ll do the chores, and a stern, cartoon caricature of a seventh grader offers the twentysomething protagonist advice on relationships, all in pouty earnest. Occasionally Yamashita’s dialogue hints at broader implications. Tamako, on an application form for an improbable modeling gig, admits that she “feels most natural when playing the role of someone else”. Dad sees in a pervasive Japanese malaise the macrocosm of Tamako’s idleness. Tamako in turn blames his generation for being all supportive– “He can’t tell me to move out. He’s failed as a father.” Yamashita’s at his best (Realism Inn, No One’s Ark, here) when riffing on such themes. A contemporary Ozu, only a little off.

Aoyama’s Backwater, from Tanaka Shinya’s Akutagawa Prize-winning Dog Eat Dog, was rougher going. In it, Kamen Rider W’s Suda Masaki plays Toma, a particularly horny seventeen-year-old who fears he’s morphing into his father, an id-driven petty hood who whacks the women he “loves.” Toma’s mother, who lost a forearm in the war and now runs a fish-gutting shop across the village, reluctantly gives the boy’s new stepmom advice on surviving her husband’s attacks. But when she learns the brute has raped her son’s teenaged girlfriend, she decides to take matters into her own hand. Though technically expert–the squalor of the fetid, junk-infested Hida River circa 1988 is gorgeously rendered; the soundtrack wreaks with polluted humidity–Backwater occupies an unsatisfyingly uncomfortable tonal middleground between the mainstream and the psychological extremes of, say, Sono Sion’s similarly themed Himizu. A simplistic feminist tractate, Aoyama’s film reminds us, ad nauseam, that men are sex-crazed pigs and women need to sharpen their knives.

Sakamoto Ayumi’s Forma offered a more subtle gynocentric (if not overtly feminist) psycho-sexual puzzle. Composed mainly of long-take wide shots, the thirty-two-year-old director’s never-ending but somehow mesmerizing first feature concerns Ayako, a bitter nit-picker who runs into Yukari, a former classmate reduced to directing pedestrian traffic around construction sites, in what we begin to suspect maybe 100 minutes into the movie was probably not the chance meeting Ayako makes it out to be. As in some simmering, Hanekean horror, Ayako offers her friend a job in her office, then abruptly demands to be addressed as a superior. She invites Yukari to a dinner party at which there turn out to be no other guests. She insinuates herself into Yukari’s fiancée’s life, hinting at a lurid past.

Sakamoto’s title warns of the intentionally confusing organization of her narrative. After a little over an hour, the film reboots and, frustratingly, begins to punch pinholes in the sympathy it’s built for Ayako’s victim. Then, nearly two hours in, a bit player from an early scene emerges as a crucial figure in a climactic, single shot, twenty-plus-minute confrontation, fragments of which Sakamoto’s shown twice before. A thrilling exasperation! But that’s not all! The film ends on a fourth, previously negligible character, who, it turns out….

Keyframe’s already treated Diao Yinan’s Black Coal, Thin Ice, an absorbing murder mystery with odd overtones of Kitano, and Lou Ye’s Blind Massage, ravishingly shot and, simply by virtue of featuring actual blind people, utterly fascinating. A third Mainland Chinese film at HKIFF that stubbornly resists being flushed from my memory is Zhou Hao’s The Night, another first feature. The twenty-one-year-old Zhou’s film, a patchwork of clichés about a prostitute (Zhou) who resists the temptation to take up with the naïve young man who falls for him, was made for nothing, shot on a consumer-grade DSLR, and populated by Zhou’s University classmates. It’s a technical disaster. Most–no really, most!–of it is out of focus. The direction of the actors is inept. The dialogue is on-the-nose. The narrative, a festival of outrageous coincidences. But because The Night, like a suddenly self-conscious high school freshman’s utterly raw production of, say, Genet, is never less than completely committed to its self-critical agenda, it’s compelling viewing. In the end, even Zhou’s film’s total incompetence feels as if it could be one of its virtues.

Korean director Leesong Hee-il’s seventy-five-minute gay-themed White Night, a 2013 HKIFF premiere, was formally rigorous and psychologically complex, a blend of Bresson and Visconti. His 2014 film, the 145-minute Night Flight, feels gratuitously bloated, unusually disengaged, hackneyed, compromised. Its love-struck high schoolers, Yong-ju, an academic star struggling to find a way to express his sexuality, and Gi-woong, the aloof leader of a gang of bullies, are both way too adorable. And horribly inappropriate pop music spoils the maybe two almost believable moments between them. While not mainstreaming the difficulties of the boys’ budding relationship, Leesong’s dutifully wagging an accusatory digit at petty extortion, educational abuse, union-busting, and capital-driven urban renewal, treating each only superficially. [Part of Gi-wong’s pizza delivery gig inexplicably involves terrorizing the enemies of whoever seems to have paid off the shop’s boss; the boys’ teachers emotionally terrorize them and turn a blind eye to some pretty obvious student-on-student assault and even rape; Gi-wong’s absent father, it turns out, has had to disappear after being fingered as a union agitator; and the derelict gay-bar Yong-ju holes up in, Night Flight, is being demolished to make way for yet another mall.] That Finecut’s sold the movie to several territories is not altogether encouraging.

Finally, this year’s HKIFF premiered Beautiful 2014, its fifth annual four short anthology, and the third it’s produced with Chinese video hosting service Youku. Native Hong Konger Shu Kei’s adaptation of Evan Yang’s short story, “The Dream on the Beach”, has the flavor of a late Wong Kar-wai film–impeccable period costumes and glossy golden lighting–but is even more elliptical. It seems to concern an eye-catching but sexually frustrated mid-century housewife who (dreams that she?) bumps into a libidinous half-naked younger man on the eponymous stretch of sand. I’ve no idea what it all may “mean,” but that (probably) is not the point.

The anthology’s opening short, Awaiting, from the heavy-handed Kang Je-kyu (Shiri), treats the predicament of families torn apart by the Korean War through the sappy metaphor of a demented old woman who, believing she’s still a newlywed, daily prepares for a husband trapped years ago on the wrong side of the DMZ an elaborate meal and then awaits his return. Get it? And the closing short, Boss, I Love You, from China’s Zhang Yuan, tracks a newbie chauffeur’s infatuation with the one-percenter whom he drives from one appointment to the next and occasionally corrals into bed after a night of revelry. Implausibly, annoyingly, not a word passes between them during the short’s thirty minutes.

Though nothing in 2014 matched 2012 stand-outs Walker (Tsai Ming-liang) and Long tou (Gu Changwei), its most satisfying short was Honorary Hong Konger Chris Doyle’s experimental documentary, HK2014–Education for All. Doyle smartly allowed the outsider schoolchildren he featured–like the chubby, rich kid who balks at a Skype appointment with his jet-setting parents and the friendless eight-year-old who plasters her folks’ squalid house-boat with religiously eclectic iconry–to compose their own voiceovers about the tribulations of growing up. He set their monologues to his own idiosyncratically composed snapshots of contemporary Hong Kong…in all its hideous, glorious diversity.