Thursday evening’s emcee, an effusive local radio host, motioned for GOD, whom he’d just introduced to a crowd of 700 devotees and some press, to come on out on stage. The Divine Presence—tall, fleshy, in jeans, trainers and his signature shades—lurched over to a sofa-chair and settled in for a ninety-minute Q&A, his long legs crossed the entire session, revealing a smidge of calf from GOD, a.k.a. Hong Kong native Wong Kar-wai, who had agreed to appear at the Hong Kong International Film Festival/Jockey Club Cine Academy to talk about his latest creation, The Grandmaster. Much of the discussion traded in classic evasions (“I don’t want to impose my ideas on my audience”), tedious lists (a half hour devoted to the names of Ip Man associates GOD had interviewed in preparing the project), and embarrassing rationalizations (Taiwanese actor Chang Chen’s scenes as kung fu expert Razor may feel poorly integrated, but such “drifting in and out of the storyline is typical of serialized martial arts tales of the fifties”). By the mid-point of the event even the deity’s disciples were visibly restless.

Three of the more interesting bits of what Wong uttered:

“We were stealing a scene for Happy Together at an Argentine railroad station. The newsstand there seemed out of another era—photos of JFK, Marilyn, Elizabeth Taylor, Che, Mao … and Bruce Lee. What struck me especially was how contemporary Lee’s face seemed. It wasn’t like those meek Chinese faces we were used to seeing in films of the fifties and sixties. It had confidence, strength. This is what my film’s about: this beauty, this appeal of the Chinese man.”

On the significance of trains in his film: “I like trains.”

The amount of time GOD says he spent training actresses to play courtesans: One year!

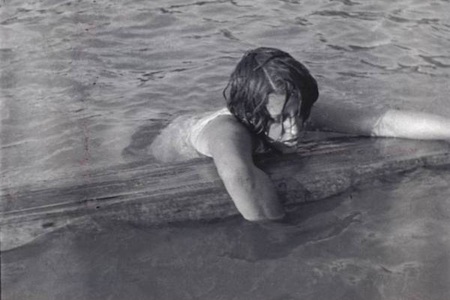

While GOD’s The Grandmaster employed to rather leaden effect all the technical magic Phantom Flex hi-speed cameras and over a hundred credited special effects artists could muster, two of what were for me the most exhilarating films at this year’s HKIFF seemed to rely on little other than their young directors’ determination to be heard. Then 21-year-old Mário Peixoto shot his only film, Limite, over eighty years ago. Long feared lost, but now traveling festivals in a World Cinema Foundation restoration, Limite tells in flashback how its three desperate protagonists came to be drifting aimlessly on a languid Brazilian sea. Back in 1931 the self-promoting Peixoto passed off stills from Limite as extracts from a new Pudovkin work and even claimed Eisenstein had so admired the film he’d penned an essay devoted to it, one Peixoto himself “translated” into Portuguese from a supposed French version of Eisenstein’s original English! But though the abstract performances Peixoto culls from his iconic cast do evoke Potemkin or Deserter, the tone and visual aesthetics of his film are much closer to those of Kirsanoff’s Ménilmontant, narrative causality giving way to dream-like meditations. Sometimes, like the perambulating Satie melodies that accompany the film, Peixoto’s camera digresses, refusing to continue following a central character then circling back to find her in unexpected circumstances. Others, it fixes on an astonishingly beautiful detail—a suicidal woman’s loose curls trembling in a gusting wind, rays of sunlight scattered across the shimmering sea. The Soviet master may not have written that essay, but its author was certainly right: “Language cannot adequately capture the experience of Limite. It was made to be felt.”

In 1995 thirty-something bad-boy-poet-filmmaker Sono Sion enlisted members of the Tokyo GaGaGa performance collective he’d formed two years earlier to shoot Bad Film, an ambitious tale of gang warfare set against the backdrop of the then-imminent reintegration of Hong Kong into China. The Baihubang, a band of recent Chinese immigrants, duke, bat, and eventually shoot it out with the ultra-nationalist Japanese Kamikazes for control of Koenji, an underground culture district just west of Shinjuku. Sono himself plays Shiro, the at-first closeted Kamikaze lieutenant who leads a group of turncoat Japanese gays and lesbians that forms an alliance with the Baihubang to establish an alternative, cut-rate, “freedom-based” black market. Shot without permits over the course of a year, Sono, his cast of (literally) thousands, and a team of camera operators commandeered commuter trains, busy intersections, and entire shopping districts where they “performed” elaborate brawls and incited political mayhem. Guerilla-filmmaking on a massive scale.

Last year Sono cut Bad Film from 150 hours of the footage he captured 17 years ago on now obsolete Hi-8 video cameras. The image quality is way more rough-and-tumble than audiences who don’t spend a lot of time on YouTube are used to, but the aesthetic is pure Sono. Maggie, who speaks no Japanese, solicits donations in metropolitan rail stations for a “Destroy the Earth Fund.” The Kamikaze’s Boss, though “fags,” “niggers,” “chinks,” and liberal-minded Japanese disgust him, carts around a severed pig head, which he refers to as his girlfriend and with which he occasionally makes out. The renegade yakuza gays romp around a public park with pre-pubescent boys playing slow-motion cops and robbers. Anarchic. Outrageous. Thrilling. Bad Film is the precursor to some of Sono’s most daring and poetic (i.e. best) works, Noriko’s Dinner Table and the little seen Yume no naka e [Into a Dream].

Another HKIFF standout, Leesong Hee-il’s White Night tracks a stone-faced Korean flight attendant who, in Seoul for a twelve-hour layover, leads his online hookup, a naïve young motorbike courier, on a quest for revenge against the gay-basher who’d left a previous boyfriend with a permanent limp. A re-imagining of a Dostoyevsky’s short story previously adapted by both Visconti and Bresson but compressed into a single evening’s time-frame, Leesong’s film successfully crossbreeds Viscontian melodrama—the steward’s ultimate indifference to but apparent desire to manipulate the courier both repels and attracts the latter—and Bressonian visual rigor. The seventy-five-minute feature played with two new Leesong shorts: Suddenly, Last Summer, in which a twelfth grader attempts to blackmail his teacher into starting an affair; and Going South, in which an army recruit on leave attempts to blackmail his former squad leader into continuing an affair. Each suggests Leesong is a filmmaker.

The shorts in Beautiful 2013, the fourth HKIFF-commissioned anthology in as many years, after Quattro Hong Kong, Quattro Hong Kong 2, and Beautiful 2012, were not nearly so successful. Most disappointing, no doubt because of high expectations, Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Beautiful New Bay Area Project features an extended, poorly choreographed, generically shot martial arts sequence in which a female dockworker (and possible alien being) kicks some corporate asshole ass. Worse, Wu Nien-jin’s A New Year, the Same Day, about a grumpy Taiwanese father who summons his wife and children to a protracted whining session, is poorly edited and performed, neither remotely funny nor cinematic. Even worse—hard to believe, I know—Mabel Cheung’s Indigo treats tropes so tired that only the most brilliant of filmmakers could’ve pulled them off. Not only do we get the cliché of the single mom forced to work (this time as a ballroom dance instructor) on Christmas Eve while her teenage daughter pouts for lack of attention but Cheung shovels on the saccharine in the form of a second, special needs [!] child who goes missing in the dense central Hong Kong traffic. Finally, Mainland cinematographer Lu Yue’s 1 Dimension, in which a court official challenges the crown prince with thorny philosophical questions re: the ontology of good and evil, consists, except for a single naturalistic shot in which the filmmakers discuss possible interpretations of the action, of stark, flattened silhouettes à la ancient shadow puppetry. Intentionally enigmatic, the pretentiously titled short, though probably the best of the bunch here, feels like one of those intellectual puzzles any solution to which is bound to be unsatisfying. Nothing nearly as hauntingly beautiful as 2012’s entries from Gu Changwei (“Long Tou”) and Tsai Ming-liang (“Walker”). Still, I can’t wait for next year’s HKIFF and a Beautiful 2014.