Taking a rare pause between graphic descriptions of his purportedly stupendous sex life in the memoir All I Need Is Love, late international film star Klaus Kinski spares a few words for his frequent director, Werner Herzog. He describes their first meeting, prior to shooting Aguirre, the Wrath of God, the 1972 Amazonian adventure that would prove a global triumph for them. Here are his recalled initial impressions of the man with whom he would make four more films over the next fifteen years: “His speech is clumsy, with a toad-like indolence, long-winded, pedantic, choppy….It takes forever and a day [for him] to push out a clump of hardened brain snot….So I’d have to smash him in the kisser.”

Later, during actual production, Kinski further proclaims, “The script is illiterate and primitive….Although I constantly try to keep out of his way, Herzog sticks to me like a shithouse fly. The mere thought of his existence here in the wilderness turns my stomach….He should be thrown alive to the crocodiles! An anaconda should strangle him slowly! No panther claws should rip open his throat—that would be much too good for him!”

Think that’s harsh? Kinski is just getting started. Fully wound up, he later calls the director “a miserable, hateful, malevolent, avaricious, money-hungry, nasty, treacherous, cowardly creep.”

In Herzog’s own 1999 documentary My Best Fiend, about his relationship with the performer who’d died eight years earlier, the director shrugs off this published abuse, calling Kinski’s autobiography “highly fictitious.” He even admits “I helped him to invent particularly vile expletives,” since Kinski thought no one would buy the book if their collaboration was painted as harmonious.

Not that it could be described as such anyway, at least much of the time. The sole film Herzog has made so far that focuses on an aspect of his own career, My Best Fiend is a portrait of a madman who also happened to be one of the world’s most riveting screen presences. For a filmmaker as attracted to “difficult” stories, production challenges and personalities as the German director, Kinski constituted a fatal attraction, sometimes almost literally so. “Together we were like two critical masses…that become dangerously explosive” on contact,” he muses. “Every gray hair on my head I call ‘Kinski.’”

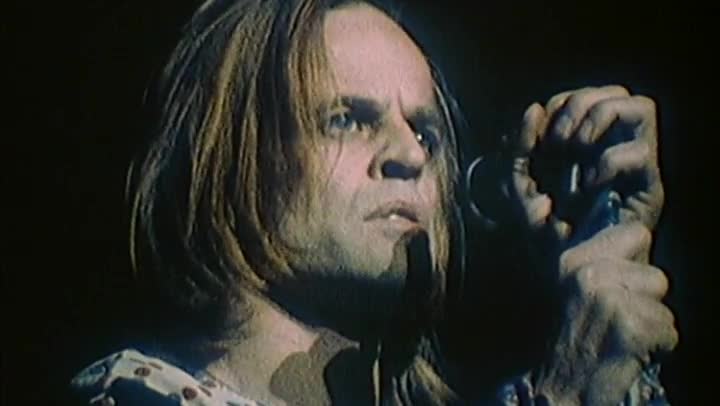

Gone almost a quarter century now (he died of a heart attack in 1991 at age sixty-five), Kinski is more than ever a cult figure today for the extraordinary intensity he often brought to even the most trivial movies. (On the other hand, he could occasionally deliver a bored walk-through performance under the least likely circumstances—for instance in what you might think a tailor-made role, as Jess Franco’s 1976 Jack the Ripper.) While the Herzog films he appeared in remain his most celebrated vehicles, perversely it was the actor’s willingness to appear in any well-paying trash that now endears him to less arthouse-inclined fanboy types: For decades he was a staple in export-ready European genre films, including numerous spaghetti westerns, horror flicks and lurid thrillers.

More striking than conventionally handsome with his shock of white-blond hair and deep-set eyes (almost invariably glaring), Kinski came by his intensity naturally. He was raised in frequently desperate poverty, drafted into the Nazi troops in 1943 at age seventeen and ended the war with a long stint in an English POW camp. Upon returning to a ruined Germany, he discovered both parents had died in his absence. Set on an acting career, he worked on stage and made his film debut in 1948. But already his professional aspirations and stormy personality were at odds. At one point he was diagnosed as schizophrenic; twice he attempted suicide. In a daft coincidence during this period, he briefly shared an apartment with thirteen-year-old Werner Herzog and family, along with numerous other boarders, Kinski alarming everyone by locking himself for two days in the bathroom (which he destroyed before police pulled him out).

Nonetheless, this “terrifying” man’s abundant talent was so evident whenever someone dared tap it that he inevitably began achieving some fame. He won raves for various solo shows, including an unlikely cross-dressing turn as the heroine of Jean Cocteau’s one-act The Human Voice. Eventually he scored significant parts in some prestigious, hugely popular films including David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago and Sergio Leone’s For a Few Dollars More. Yet he also accepted dozens of assignments in cheapo exploitation flicks, bragging later “I don’t ask about the titles or directors. All that’s important is getting money.” Among them were the likes of The Pleasure Girls, If You Meet Sartana Pray for Her Death, Pray for Your Death, Lover of the Monster and How Did a Nice Girl Like You Get into This Business?

Thus by the time Herzog came along with an ambitious idea for his fourth narrative feature, Kinski was notorious—as both a genius and a cash-grubbing joke. His “Jesus Christ Savior” tour performing radically revised New Testament texts got him heckled by hippie college kids as a fallen anti-establishment hero who’d completely sold out. My Best Fiend opens with a long excerpt from the filmed record of one such onstage meltdown. When not “in character” as a wild-eyed Messiah, he calls the audience “scum” and physically batters anyone who gets too near. It’s a grotesque spectacle that, like a train wreck, you can’t turn away from.

That highly publicized debacle—not to mention the star’s already infamous womanizing and off-stage temper—might have warned off any other young director. But instead it only heightened Herzog’s sense that this divine lunatic had to play his Aguirre, a 16th-century Spanish conquistador who goes mad on a doomed quest to find a mythical “city of gold” in Peru. Shooting this under-budgeted period epic on remote locations with a large cast and multinational crew, Herzog had difficulties enough. But worst of them all was Kinski, who in Fiend’s process behind-the-scenes footage we see throwing various tantrums. “You have to beg me! David Lean and Brecht did!” he screams when given some simple instruction. During another tirade, he hits an extra so hard with a sword that the unfortunate local (who decades later recalls the actor as “diabolical”) got a permanent head scar despite wearing a protective metal helmet.

Yet his performance remains the mesmerizing centerpiece of a great film. Their reputations greatly enhanced upon its release, Herzog and Kinski’s ongoing collaboration would loom so large in both their careers you might easily forget they only made five films together: The others being Nosferatu the Vampyre, Woyzeck (both 1979), Fitzcarraldo (1982) and Cobra Verde (1987). All presented major challenges, but Fitzcarraldo was famously bedeviled. Returning to Peru, Herzog now dramatized the story of a real-life 19th-century entrepreneur who’d had an entire steamship transported over a mountain. The director insisted on his recreation being just as logistically near-impossible. Then there was the human tsunami of Kinski, whose rage at the production’s “pig food” and other alleged discomforts were again captured for posterity, this time via documentarian Les Blank’s classic making-of memento Burden of Dreams. At one point Kinski was so out of control he purportedly shot blindly into a tent crammed with forty-five extras, blasting one man’s finger to smithereens.

“It’s always very difficult to explain that he had a great human warmth, which abruptly could turn into rage of unimaginable proportions,” Herzog explains in My Best Fiend. “[We] complemented each other in a strange way. I think he needed me as much as I needed him.”

Despite his reputation for violence and irrationality, Kinski wasn’t a nutcase 24/7. It’s startling in Fiend when we see actor and director greet one another with great affection at the Telluride Film Festival in the 1980s, practically finishing each other’s sentences like an old married couple as they discuss their ongoing collaboration. Kinski looks relaxed, even radiant in Herzog’s company. Yet this episode, the latter tells us, came not long after he’d been made so furious by the star that he’d actually considered firebombing Kinski’s house. (During Fitzcarraldo, tribal extras had offered to kill the ever-ranting thespian, thinking that would be a great help to the steady-nerved Herzog.)

We also hear fond reminiscences from co-stars Eva Mattes (Woyzeck) and Claudia Cardinale (Fitzcarraldo), which are all the more striking because as Herzog notes, very few women ever had anything good to say about the often crude, abusive Kinski. (In his memoir, he paints himself as constantly busy satisfying the needs of besotted nymphomaniacs, using language baser than you’d find on a YouTube comment thread. His two daughters, including famous actress Nastassja Kinski, subsequently claimed physical abuse from a father they grew estranged from long before his death.)

If Klaus Kinski were himself the subject of fiction, he would defy credibility—on- and by all reports off-screen, he was larger-than-life. The fiendishly entertaining My Best Fiend may will make you glad you never had to risk his unpredictable wrath in the flesh. But as Herzog himself knows better than anyone, it’s a blessing he’ll always be available on celluloid, where his brilliance and frequent belligerence still burn like a supernova.