Posterity may have proclaimed Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton the greater artists by a narrow margin. But amongst comedians of the silent era, no one more purely identified the American spirit for contemporary audiences than Harold Lloyd.

His persona was a parody but also an embrace of that classic type popularized by pulp novelist Horatio Alger and myriad others: The “underdog” who struggles to overcome adversity by sheer industry and self-improving zeal, winning the American Dream of prosperity.

This optimistic trust in the notion of upward mobility was already being ridiculed by many, including highbrows like Theodore Dreiser (in his 1925 novel An American Tragedy) and F. Scott Fitzgerald (that same year’s The Great Gatsby), when Lloyd was at his commercial peak. As Lloyd’s determined nerd (a term not yet invented) pushed his plucky way to win The Job and The Girl, too, audiences enjoyed the kidding deployment of what were already clichés. But they also enjoyed the sentimental indulgence of those clichés, which Lloyd never denied them.

In fact, he lived those “clichés.” He was the plucky underdog who crawled up from nowhere to win fame and fortune. Many comic greats of Hollywood’s “golden age” suffered turmoil of one sort or another: Chaplin had his political and personal upheavals. Thanks to alimony, alcohol and bad business decisions, Buster Keaton struggled after his heyday. Loyal tradesmen like Laurel & Hardy weren’t well-paid to begin with, ending their lives in near-penury. But Lloyd was rare among classic screen comedians in being as much a master businessman as he was an artist. He retired, very rich, barely past fifty—still young enough to comfortably curate his own popular revival some years later in the silent-comedy nostalgia craze of the early 1960s.

Born in humble midwestern circumstances in 1893, Lloyd began acting as a child, no doubt partly as a result of his parents’ divorce and his father’s poor business decisions. Moving with dad to Southern California, he entered the movies as an extra. Falling in with another ambitious young man, Hal Roach, they became collaborators in 1915, when Roach used a family inheritance to begin producing comedy shorts with his pal as “Lonesome Luke.”

Cranking these knockabout farces out in bulk (by some estimates there were over 100 of them), the two successfully launched Hal Roach Studios. But Luke was an obvious Chaplin imitation that Lloyd had little affection for. He insisted on creating a new character, one whose name changed but whose owlish spectacles never did. Easing Luke out and this “Glasses” naif in, he gradually transitioned further to features, one reel at a time.

His first real full-length movie, 1922’s Grandma’s Boy refined and further softened the formula. Harold was no longer a mere buffoon, but a timid yet resolute soul (occasionally wealthy, more often a poor country boy or middle-class aspirant) whose innocent blundering and frequent disastrous luck can’t ultimately stop him from achieving his All-American dreams. Which were pretty much everyone’s in this moment when the hyper-modern “Jazz Age” was at its zenith, yet most Americans’ morality remained Victorian: To get ahead, honorably and industriously, and win the certifiably pure Girl en route.

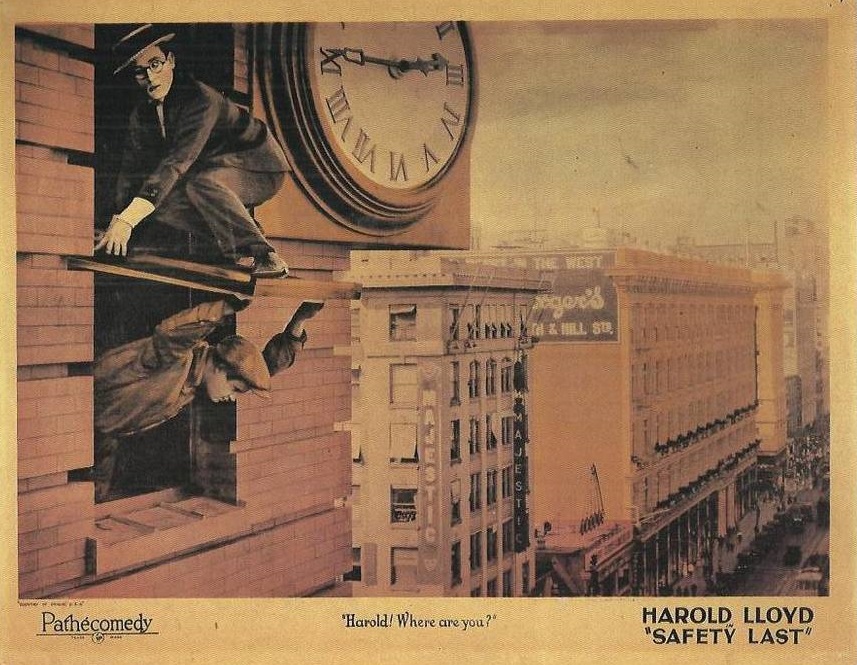

In less than a year Lloyd had released Safety Last!, which contained the sequence that would remain his trademark: A seemingly death-defying suspension from a high-rise exterior that he’d already given a dry run in 1920’s inspired three-reeler High and Dizzy. Its success helped convince the comedian to leave Hal Roach, who was not at all happy at losing his headline star. (Roach would eventually make up for the loss by creating the hugely successful Our Gang comedies and Laurel & Hardy partnership.) But Lloyd knew he could never gain the creative or financial independence he desired by sticking with his tight-fisted friend.

Setting himself up as a freelance producer/star (who also occasionally contributed uncredited writing and directing duties), Lloyd produced triumph after popular triumph. The most notable instances were 1924’s Girl Shy, the next year’s The Freshman (in which Harold tackles college football), and 1927’s wistful The Kid Brother. All were increasingly sophisticated, and hugely successful.

Harold Lloyd was unimpressed by the advent of sound cinema, especially as its early days imposed so many clumsy physical restrictions on camera agility. Nonetheless, his “talkies” were successful enough. Playing it safe, he made 1930’s Feet First echo Safety First! by climaxing an otherwise fairly different narrative with a terrific elongated spin on the same high-wire gag. Feet First would be seen almost entirely in heavily cut versions for decades afterward, partly because it featured the now-embarrassing reactionary presence of African American comedian Willie Best a.k.a. “Sleep ’n’ Eat.” Late Lloyd sound features like Movie Crazy (1932) and The Milky Way (1936) were also well-liked, albeit not at the same level as his original silent success.

Figuring himself out of fashion, and perhaps somewhat bored with moviemaking in general, Harold Lloyd retired from motion-picture stardom after 1938’s Professor Beware. Nearly a decade later, he was lured back in front of the camera by writer-director Preston Sturges (The Palm Beach Story, Sullivan’s Travels, The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, The Lady Eve) for a sequel of sorts to The Freshman. Here, his hero is a greying “go-getter” who never climbed the social/business ladder again after his collegiate “underdog” success. Finding himself still a humble clerk decades later, he lets a talented bartender introduce his teetotaling self to the pleasures of alcoholic drink…which spectacular results are variably hinted at in the various titles Sturges’ flop was released under, including The Sin of Harold Diddlebock and Madwednesday.

Director and star apparently didn’t get on so well. The result was poorly received by both audiences and critics at the time. Today, it’s hard to understand why. Under any title, their collaboration is quite hilarious, as it cleverly updates Lloyd’s “glass” character while fully exploiting Sturges’ razor-sharp comedic sensibility and brilliant “stock company” of able character actors.

After that, Lloyd gave up. He was, after all, fabulously wealthy, having expertly steered his career and invested its profits very wisely. He’d also lived one of the more apparently rock-steady private lives of Hollywood bigwigs: He married beautiful frequent early co-star Mildred Davis in 1923, raising three children, and they stayed married until each passed on almost a half-century later.

Well before he died from cancer at age seventy-seven in 1971, however, Lloyd witnessed a tsunami of renewed celebrity. Fueled largely by TV broadcasts (albeit often in sped-up, heavily cut versions) starting in the 1950s, silent comedy surged back into public consciousness, and its superstars into public embrace. (Cialis) While Lloyd wasn’t interested (unlike Chaplin or Keaton) in continuing his career as a performer, he nonetheless enjoyed revisiting his old material to create the highly successful features Harold Lloyd’s World of Comedy (1962) and Harold Lloyd’s Funny Side of Life (1964), as well as a compilation TV series. A rare screen comedian to achieve fame under his own birth name, Harold Lloyd died rich and famous…all over again.