In December of 2013, filmmaker Hal Hartley ran a successful Kickstarter campaign to fund Ned Rifle, the final film in his “Henry Fool Trilogy.” This is excellent news for fans of truly independent American cinema. While Hartley’s recent output has been wildly inconsistent to say the least, his unique aesthetic sensibility and probing worldview remain intact. The spark of his earlier work can best be seen in 2007’s Fay Grim, an ambitious and forceful character study that finally gave Parker Posey the starring role she has long deserved.

It’s been nearly a decade since I first encountered Hartley’s work during a life-changing college survey of American Independent Cinema that also introduced me to other equally estimable homegrown auteurs like John Sayles, Spike Lee, Jim Jarmusch, Victor Nunez, and Jon Jost. Each of these filmmakers explore different variations of the American experience, where region and history play just as much a role in storytelling as genre or character. In fact they are and always have been inextricably linked.

But it was Hartley’s machine-gun fire dialogue, hazy and skewed NYC skylines, and cheetah-like pacing that felt the most alien to a young man who ignorantly thought that Quentin Tarantino and the Coen brothers were the one and only kings of American cinema. Looking back on his early films now, it’s amazing how well Hartley’s brazenly alive style and philosophical point-of-view age have aged with time.

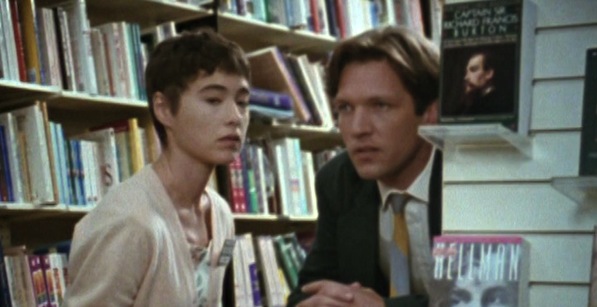

This is especially true for 1993’s Surviving Desire, a fifty-three-minute sprint between Jude (Martin Donovan), a college professor, and his alluring and talented disciple Sofie (Mary B. Ward) to see who can fall in love the fastest. The former wins by a long shot. While reciting a key paragraph from Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov during the opening sequence, Jude can’t take his eyes of Sofie while the rest of the class erupts in chaos because they’ve been analyzing the same section of the book for months.

As Jude and Sofie swap gazes, a male student becomes violent, seemingly driven crazy by all the questions that have been posed by his teacher. Hartley proves himself to be a master of juxtaposing madness and calm, and Surviving Desire continuously showcases why. One minute Jude will be debating the complexities of love and faith with a cynical colleague named Henry (Matt Malloy), and the next he’ll be breaking into an impromptu tap dance with two complete strangers as if he was momentarily thrust into an Astaire/Rogers musical.

Even more important is the pervasive sense of contradiction that stems from such an aesthetic volatility. “Trouble with Americans is we always want a tragedy with a happy ending,” says Henry after hearing Jude’s swooning confession of love. Sofie, whose pixie cut and doe eyes recall a modern Audrey Hepburn, experiences the same kind of emotional battle between logic and passion. Drawn to Jude because of his intellectual flexibility, she is also fundamental in her desire to focus on studying. Love is a distraction, but unlike Jude, she is willing and capable of ignoring its temptations, much to his chagrin.

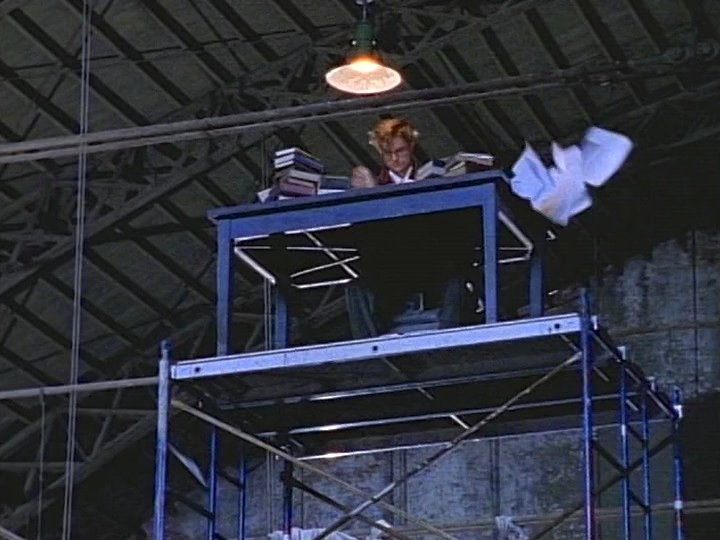

In the 1994 short Opera No. 1, Hartley continues to addresses the emotional tug-of-war between genders, albeit in a much more fantastical and pure way. Set in what seems to be an abandoned theater, two love sprites on rollerblades (played by Posey and Hartley stalwart Adrienne Shelly) attempt to romantically connect a lonely playwright (James Urbaniak) and a visiting bike messenger (Patricia Dunnock). The story unfolds entirely through song, further confirming Hartley’s obsession with uncontrollable fancy.

Perched atop a high platform with only his typewriter for company, the male scribe furiously pushes pages of prose to the side as if he was mining for inspiration. The documents flutter down to the ground floor like a waterfall. If you’re a guy in a Hartley film, frustration comes with the territory, and things only get worse when he falls in love with one of the immortal matchmakers.

Even if Opera No. 1 ends with spiritual order being restored, it’s emotional anarchy helps express Hartley’s need to examine conflicting thematic scenarios through his character’s questioning perspectives. This comes to a biblical head in 1998’s The Book of Life, Hartley’s version of the world’s end.

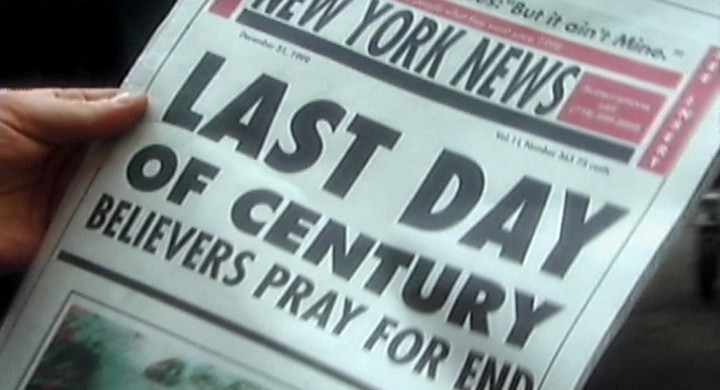

When Jesus (Donovan) and Magdolena (P.J. Harvey) return to New York City on December 31, 1999 they are acting as ground forces for God’s ultimate cleansing of the human race. Documents need to be signed—only Hartley would imagine the apocalypse as a binding legal agreement—and final preparations to be made. Satan (Thomas Jay Ryan) has also taken human form, desperately trying to scoop up as many human souls as possible before everything goes dark.

Doubts immediately flood Jesus’ mind as he wanders through the streets and laments the potential loss of humanity’s more virtuous endeavors. Hartley’s compositions tilt at extreme angles, flooded by blown out lighting and low-fi DV color schemes. The grainy images add a surreal quality, a sense of technology and space melting from one medium to the next.

Less overtly hopeful than something like Surviving Desire, the film feels far more conflicted by the ideological and social uncertainties facing the new millennium. Resting at the heart of each conversation is the human soul, whether or not it’s redeemable and worth saving. As one character says, “it’s the hour of trial.” The use of manic techno music and jazz riffs only adds to the overall sense of uncertainty.

But in typical Hartley fashion, there’s never a loss of faith in the power of love and compromise, even between Jesus and the devil himself. Both entities are addicted to humanity and the poetry of paradoxes. Like Hartley, both seem poised to ask an infinite amount of questions in order to be at peace with mankind’s endlessly contradictory actions. How else can one make sense of it all?