As reflected in my tweet above, I didn’t much take to The Grandmaster when I first saw it at the Berlinale last February. I found it to be a compromised and largely incoherent enterprise that reeked with the slick commercialism of a two-hour perfume ad. The “neo-kung fu” Wong was expected to deliver seemed indistinguishable from the Hollywood action mishmashes of Guy Ritchie, Timur Bekmambetov and Michael Bay: twitchy, over-processed sensationalism in place of substance. Wong literally drowns the fight scenes in rainy atmospherics, with a peculiar slow-mo fetish for puddles and feet.

My Berlinale screening played out like a series of kung-fu showdown clichés that gradually dissolved into a mess of scattered fragments, with lead Tony Leung disappearing for long stretches while others take their turn at kicking ass: like a kung fu three-ring circus shot in HD. Wong seemed hamstrung by commercial demands to showcase his all-star cast at the expense of narrative sense. Two characters in particular are thoroughly underdeveloped to the point of being expendable: a tough guy played by Taiwanese star Chang Chen, and the title character’s Chinese wife, played by Korean actress Song Hye-kyo, who does nothing but sit prettily and attract Korean viewers (conveniently, her character doesn’t like to speak, thus sparing us from some awful overdubbing). Their removal from the film altogether might make for more comprehensible viewing; but the demands of appealing to a pan-Asian audience seem to trump Wong’s artistic integrity.

Those were my impressions back in February, and I figured that would be it between The Grandmaster and me, even as it finally makes its U.S. premiere this month. But of course, with Wong it’s never that simple. For one thing, I might not have actually seen the same Grandmaster that others have seen, or will see. The cut that premiered in Berlin (reportedly intended for European distribution) is not the same one Harvey Weinstein is dropping on the U.S. (whether that means it’s actually an improvement remains to be determined). And neither version is the same as the one that originally premiered in Asia to generally good critical and extremely good commercial response. It is this version of The Grandmaster that critic and Chinese cinema expert Shelly Kraicer saw in offering an invaluable assessment of the film in Cinema Scope, which ultimately convinced me to give the film another try.

Among Kraicer’s many insights, the one I find most valuable is how the film adopts a relationship to Chinese history that’s radically new for Wong, and is critical to appreciating its disruptive story structure. While some of his previous films are set in historical periods, this is the first to make history its explicit subject, in depicting how its characters respond to cataclysmic events (namely, the Japanese invasion of China, World War II and the Communist Revolution that sent millions of exiles from the mainland to Hong Kong), and how their responses not only alter their lives, but the passing on of traditions and histories to the next generation. The Japanese wartime occupation tears through the story fabric of The Grandmaster, preventing its two leads, martial arts masters Ip Man (Tony Leung) and Gong Er (Zhang Ziyi) from deepening a relationship that could potentially have altered not only their lives but the course of martial arts history. The entire second half of the film is told with backward glances at what happened and what might have been, and how one grandmaster survived while another did not, taking an entire family legacy of martial arts secrets with her to the grave.

I came to appreciate this and other virtues of The Grandmaster while watching the Chinese version on DVD, a viewing situation that yielded multiple dividends. Watching the film at home with a Chinese companion permitted us to discuss the film as it played, unpacking the highly aphoristic dialogue laced with multiple meanings that often don’t translate well in English and may not even register in one sitting for Chinese viewers (on my first viewing, much of the exchanges played like a babble of mystical mumbo jumbo). The seemingly haphazard narrative made a lot more sense in light of the theme of history’s bomb-like disruptiveness. To borrow from what someone once said about The Shining, The Grandmaster seems like a film to be watched not only more than once, but forwards and backwards, which watching on video conveniently affords. It will be worth comparing differently the film’s narrative is structured between the versions; at least the Chinese version doesn’t have the utterly stupid European ending that has Tony Leung asking “What’s your style?” directly to the audience as if he were in a TV commercial for hair products.

Perhaps most significantly, I felt less bombarded by sensory visual spectacle watching the film on DVD, which allowed me to notice nuances and variations to how Wong films his fight scenes. There are no less than 14 fights in the Chinese version, about one sixth of the total running time: a healthy dose of action for a director who’s never filmed fights before (his blurry, impressionistic wuxia sequences in Ashes of Time amount to anti-action filmmaking). Curiously, a key showdown between Chang Chen and Tony Leung that was one of my favorite scenes in the European cut is missing in the Chinese. What fascinates me most about the fight scenes is that they don’t adhere to a singular style, but are remarkably varied from one moment to the next, employing whichever technique or techniques are suitable to the dramatic requirements of a given situation.

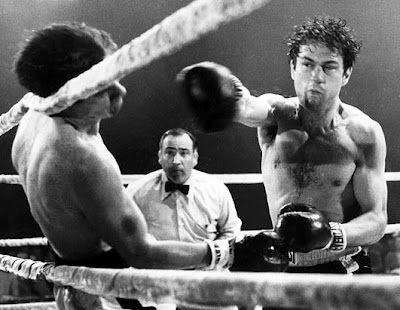

For this reason I disagree with the assertion made by critic Nick Pinkerton, in his lucid, rapturous appreciation of the film for Moving Image Source, that “the action is never less than legible.” The film’s action is no more consistently legible as it is consistent in style. It shifts from Bruce Lee-style exhibition kung fu to blink-and-you-miss-it blur effects, or from Tsui Hark-esque gravity-defying wire work to garishly artificial CGI, and not just between fight scenes but between shots within a single fight. Wong indulges in a martial arts cinema smorgasbord that’s reminiscent of the “every trick in the boxing movie book” Martin Scorsese employed in staging Raging Bull’s matches.

History will judge whether this hyper-hybrid approach is a new kind of martial arts filmmaking or really amounts to “no style” (a label adopted by Ip Man’s most famous disciple, Bruce Lee, when he broke from Ip’s Wing Chun school and started pillaging techniques from all sources to form his own Jeet Kune Do style). Either way, what’s presented in this film should not be judged wholesale, but as a multivalent attempt at representing how an entire lexicon of kung fu film techniques can be synthesized and re-synthesized in endless combinations. One doesn’t have to like or dislike them en masse—I’m personally baffled by the adulation that Kraicer, Pinkerton, and others lavish on the film’s de facto set piece, a climactic duel between rivals Gong Er (Zhang Ziyi) and Ma San (Zhang Jin) that’s CGI’d to within an inch of its life, and feels simply too processed for its kung fu fighting to register as real (the kindest things I can say is that it suggests a Guy Maddin homage to Josef Von Sternberg and King Hu; and the movement of a train in the scene creates a weirdly hypnotic celluloid flicker effect, one that’s all the more bizarre in that the train itself is computer generated, a strange blend of new techniques and old aesthetics). On the other hand, I now appreciate the brilliance of Wong placing this climactic fight long before the film ends; in a conventional action film, this would seem like poor placement, but here it’s intended as a fatal moment of destiny whose consequences ripple through the rest of the film, and pours out into a larger awareness of all the knowledge and art that’s been lost to history.

It’s that lingering sense of all that might have been in The Grandmaster—both in the story it tells and in itself as a film—that defines its lasting significance for me. While I still balk at several aspects (the slicker-than-slick production design; the dubious retaining of Asian stars in extraneous roles), I see them as less successful iterations in a series of attempts by Wong to find new ways to revitalize a well-worn genre. It’s not so much the end result that matters (assuming that there even is an “end,: given the different versions of the film that have and will probably continue to materialize). Instead, I value The Grandmaster as an open-ended arena for critical engagement, one as much defined by the curious viewer as by the vaunted filmmaker.