We live in a culture with unprecedented access to movies—through DVD and Blu-ray, streaming subscription services, and SVOD. And it’s not just new and recent films and TV programming; classic Hollywood films, international movies, documentaries, experimental film, and even hundreds of silents, many of them in restored and remastered editions, are available through physical purchase or streaming rental. The inevitable trade-off is the loss of a lively repertory culture of theatrical film revivals.

The good news is that revivals and restorations can still be big-screen events—just look at the attention that Dekalog and Chimes at Midnight and One-Eyed Jacks received when they returned to the big screen—and dedicated home-video distributors continue to make these newly restored editions accessible on disc and various streaming services for anyone out of reach of a cinematheque or a dedicated film festival.

Now here’s my list of the archival events of 2016—the debuts and rediscoveries of classic films and cinema landmarks, the restorations of great films, and the revivals of previously unavailable or inaccessible movies. I confess to my biases up front: This selection focuses on restorations available to American audiences in 2016 regardless of where they live (thus King of Jazz, which only played a few cities, is not in contention), favors films previously inaccessible to audiences, and reflects my own subjective historical and aesthetic inclinations. Your mileage may vary. If you bristle at the idea of the “best,” think of this of a survey of the breadth of restorations and rediscoveries that film lovers now have a chance to see, regardless of where they live, as long as they have a web connection and a Blu-ray player.

1. Chimes at Midnight (Janus Films theatrical, Criterion Blu-ray and DVD)

The film that Orson Welles proclaimed his favorite (“If I wanted to get into Heaven on the basis of one movie, that’s the one I would offer up”) suffered a fitful American release 1965, decades of legal limbo that effectively kept it off screens and home video, and a legacy of battle-scarred prints with murky soundtracks for those few special event screenings. After years of negotiating the tangled rights and gathering materials, the film was restored in 2015 and, on New Year’s Day 2016, given its first official American theatrical showings since the 1960s. It is magnificent and nothing short of a revelation. Chimes at Midnight is one of Welles’ unqualified masterpieces, his greatest film according to many critics, and a personal project that took decades to finally bring to the screen, and for many Americans, this was the first opportunity to see it. The restoration produced by Spain’s Filmoteca Española was created from the original negative, and the American release has given additional digital restoration. For those not fortunate enough to have a theatrical screening handy, Criterion gave the restoration a worthy special edition on Blu-ray and DVD.

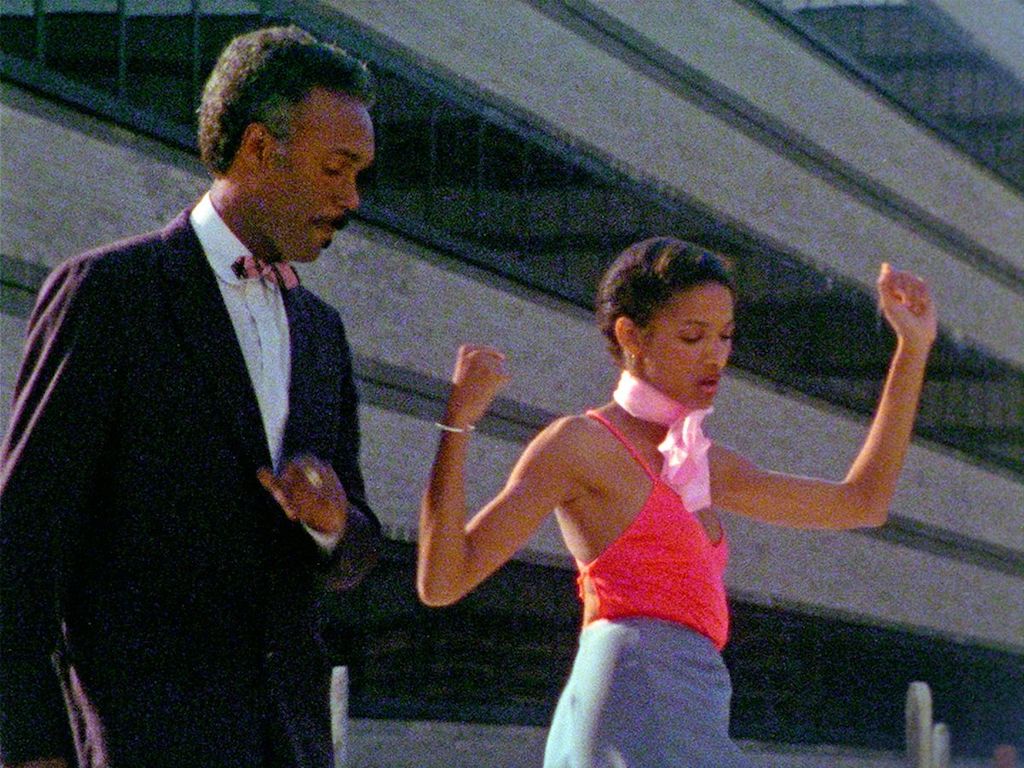

2. PIONEERS OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA (Kino Lorber, Blu-ray, and DVD)

The legacy of African-American filmmaking—specifically films made by and for African-American audiences before Hollywood began integrating its casts—is largely unknown to even passionate film buffs, partly because the films were rarely seen by white audiences in their day, and partly because so few of the films had been preserved with the same dedication given to the maverick films of Hollywood. Pioneers of African-American Cinema is the first comprehensive effort devoted to collecting and preserving feature films and shorts produced between 1915 and 1946 for black audiences, most of them made by African-American filmmakers. Many of the films have been previously available in poor editions, but many others are available for the first time—the slapstick shorts Two Knights of Vaudeville (1918) and Mercy, the Mummy Mumbled (1918); aviation melodrama The Flying Ace (1926); Zora Neale Hurston’s landmark ethnographic films Zora Neale Hurston Fieldwork Footage (1928) and Commandment Keeper Church, Beaufort South Carolina, May 1940 (1940); and James and Eloyce Gist’s amateur evangelical films Hellbound Train (1930) and Verdict: Not Guilty (1933). While these films have undergone no extensive restoration, they have been professionally mastered from the best existing materials, which means that damage and wear are visible but there is clarity to the image (many of the films look quite crisp) and the soundtrack. This is a true work of cinematic curation and preservation.

3. Losing Ground (Milestone, Blu-ray, and DVD)

The independently-made feature by American playwright and filmmaker Kathleen Collins was produced in 1982, making it one of the first features directed by an African-American woman. That alone makes it worthy of attention, but Collins proves to be an intelligent, insightful, and nuanced filmmaker. It’s a film of conversation and argument, of relationships and self-knowledge, and its sexual politics are as sophisticated as its personal odysseys. The film never received any real distribution or a theatrical run, and remained unknown outside of scholarly circles for decades—it might have stayed that way if not for the efforts of Milestone Films. Losing Ground received a few special theatrical showings in 2015, but for the most part, the special-edition disc, released in 2015 with additional films by Collins and an illuminating collection of interviews, in the form in which most of us were finally introduced to the film. It never received the recognition it deserved in Collins’ lifetime. All the better to celebrate its revival and rediscovery.

4. Private Property (Cinelicious, theatrical, and Blu-ray+DVD)

Long considered lost until it was restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive and rereleased in 2016, Private Property isn’t a lost masterpiece, but it is a terrific little independently-produced thriller—both a handsome production and a visually evocative world, taut with palpable tension. The directorial debut by Leslie Stevens, a playwright, screenwriter, and protégé of Orson Welles, this 1960 American indie is a neat little sexually charged psychological thriller starring Corey Allen and Warren Oates as drifters with a sociopathic streak crashing the sunny California culture of affluence and trophy wives. The simmering resentments of class and money, and the confusion of sex, desire, and PowerPoint this film forward to the socio-political concerns of late-sixties and early-seventies cinema.

5. BELLADONNA OF SADNESS (Cinelicious, theatrical and Blu-ray)

This lost 1973 classic of Japanese animation is indeed an erotic drama, but perhaps not what you might think. Set in an unnamed kingdom in an abstracted medieval Europe, it’s a part subversive folk tale, part rock-ballad musical, and part experimental filmmaking. Whatever you want to call it, it’s nothing like the manga serials or sexually explicit anime horrors that come to mind in the intersection of Japan, animation, and erotica. This has more in common with animated outliers like Fantastic Planet (France, 1973) and the Czech New Wave masterpiece Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970). From abstract sexual imagery to strobing Peter Max pop-art designs to delicate watercolors and Euro-style sketches, Belladonna of Sadness—restored to its full length and to its visual vibrancy and intensity by Cinelicious—is a unique artifact from a time when animated features could aspire to fine art and experimentation for adult audiences.

“A fantasia by Marcel L’Herbier,” reads the opening credit of this 1924 French melodrama, and indeed it is a wonder of cinematic modernism and visual innovation. The story is conventional stuff with all sorts of flamboyant schmaltz, but the production is a delight, with expressionist design by future filmmakers Alberto Cavalcanti and Claude Autant-Lara, and a magnificent science-fiction laboratory designed and constructed by Fernand Léger (who also created the opening credits), brought to life with cinematic brio and dazzling visual intensity by L’Herbier. Restored by Lobster Films from the original nitrate negative and released stateside by Flicker Alley, the angels of silent-film rarities, this one now is streaming on Fandor.

7. A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY (Criterion, Blu-ray, and DVD)

The fourth feature and first masterpiece by Taiwanese filmmaker Edward Yang (Yi-Yi) is a sprawling, personal drama about the generation of kids born to the refugees who fled Communist China to Taiwan—specifically, an angry, alienated teenager (Cheng Chan) unsure of his place and searching for an identity in a culture that isn’t strictly Chinese. Unlike fellow Taiwanese filmmakers, Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Tsai Ming-Liang, Yang’s early films were rarely seen in the U.S. outside of film festival showings, and this 1991 feature wasn’t released in the U.S. until 2011. Criterion presents the 4K digital restoration by the Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project for its American home-video debut.

8. ONE-EYED JACKS (Criterion, Blu-ray, DVD)

The only film directed by Marlon Brando was troubled from its origins. The production went disastrously over schedule and over budget due to the perfectionist tendencies of its director; the rough cut was yanked from Brando’s hands and cut down by the studio; the 1961 release was a financial flop, and the film was allowed to fall into the public domain, essentially orphaned and abandoned. This year it was rescued from PD purgatory with a restoration by Universal Pictures and the Film Foundation from the original 35mm VistaVision negative, and the stunning new presentation reveals a vital western with vivid primal imagery, themes of friendship and betrayal out of Peckinpah (whose original screenplay was rewritten), and jagged drama honed with Method exercises and improvisation. It premiered at Cannes 2016 and arrived on disc from Criterion after select theatrical screenings in the U.S.

The Murnau Foundation continues its fine work restoring the silent-film legacy of Germany’s master filmmakers with this restoration of Fritz Lang‘s first masterpiece. Technique, sensibility, cinematic vision, and story all come together in this epic drama of love, death, myth, and sacrifice, a mix of supernatural drama and parable produced in the shadow of World War I. The fantastical sets and groundbreaking special effects still inspire awe in their delicacy and grandeur, but Lang’s baroque designs and spectacular magic are put to a story of somber poetry rather than spectacle. It premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival, and the restoration was brought to theaters and released on disc in the U.S. by Kino Lorber.

Two years before the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the right to vote, Mothers of Men imagined a future of national suffrage and political equality through the story of a passionate lawyer (Dorothy Davenport) who is elected Governor as the Women’s Party candidate and faces chauvinistic attacks by the press and shady business interests. Who would have thought that this 1917 mix of social commentary and shameless melodrama would resonate so much today? As filmmaking, it’s clumsy and overstuffed with explanatory intertitles, but still, this is a remarkable example of socially conscious cinema with a progressive message. Restored by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival and premiered there this year, it’s not on disc yet, but Fandor is streaming the restoration.

Special Mention: RAISING CAIN: DIRECTOR’S CUT (Shout! Factory, Blu-ray)

Along with the Blu-ray debut of one of Brian De Palma‘s most polarizing films, Scream Factory’s Raising Cain: Collector’s Edition includes Peet Gelderblom’s “fan” recut that reorders the film to De Palma’s original plan as best he could using only footage from the release version. De Palma was so pleased with the exercise that he insisted it is included as a “Director’s Cut” supplement, and Gelderblom got the chance to remaster his cut with restored materials. This vision of Raising Cain parodies, embraces, celebrates, and experiments with psychodrama, and plays on De Palma’s thematic obsessions and stylistic trademarks (and our expectations of them) to create a film that may indeed have been a little too far ahead of its time. Now it looks cheeky and clever and self-aware—the ultimate De Palma puzzle box. Hard to call it a “rediscovery,” but it is indeed a restoration, if only of a glimpse of a vision that was never realized in its time.

Honorable mentions:

The Chase (Kino Classics, Blu-ray, DVD): This 1946 film noir has been around for decades on inferior (and some downright miserable) VHS and DVD editions, but this release presents the marvelous restoration that the Film Foundation funded in 2012.

La Chienne (Criterion, Blu-ray, DVD): The second sound film by Jean Renoir and arguably his first masterpiece shows Renoir already using sound both subtly and creatively back in 1931. The American disc debut is mastered from a new 4K digital restoration and also includes a new restoration of Renoir’s debut sound film On purge bébé (1931).

The Daughter of Dawn (Milestone, Blu-ray, DVD): This fictional 1920 drama of tribal life, featuring a cast made up entirely of Native Americans, was thought lost for almost a hundred years. Milestone gives the film (which is now on the National Film Registry) its home-video debut in a special edition.

The Dekalog (Criterion, Blu-ray, DVD): It’s been on disc and on American screens before, but the new 4K digital restoration of Kieslowski‘s ten-part intimate epic, mastered from the original 35mm camera negatives, is astounding.

The Immortal Story (Criterion, Blu-ray, DVD): Orson Welles’ first color film and his final completed fictional feature (barely qualifying as a feature at fifty-eight minutes) is a small jewel of a film, dreamlike and ephemeral and gorgeous. It was conspicuously absent from home video in the U.S. until Criterion’s disc release, via a new 4K master from the original 35mm camera negative.

Paris Belongs to Us (Criterion, Blu-ray, DVD): Jacques Rivette‘s 1961 debut feature made its long-awaited U.S. home-video debut in a Criterion edition, a new 2K digital restoration mastered from the original camera negative.

A Touch of Zen (Criterion, Blu-ray, DVD): King Hu’s chivalrous romantic adventure of grand sword battles fought with the grace of ballet is a masterpiece of Hong Kong cinema. Criterion presents the new 4K restoration by the Taiwan Film Institute and L’Immagine Ritrovata.

Try and Get Me! (Olive, Blu-ray, DVD): One of the great lynch-mob movies ever made, and one of the most caustic social commentaries of anxiety and fear, this 1950 film noir was restored by the Film Noir Foundation and given its American disc debut by Olive Films.

Wim Wenders: The Road Trilogy (Alice in the Cities/Wrong Move/Kings of the Road) (Criterion, Blu-ray, DVD): Wenders continues the restoration of his film library with these three defining early features, and Criterion gives them a terrific box-set edition with two early Wenders shorts and other supplements.

Woman on the Run (Flicker Alley, Blu-ray+DVD): The Film Noir Foundation restoration premiered at the 2015 Noir City festival and came to disc in 2016, finally displacing decades of dreadful home-video editions. Flicker Alley also released FNF’s 2014 restoration of Too Late for Tears. Both are terrific special editions.