[Editor’s note: As one film season (year-end lists) comes to a close, another begins (Oscar-predicting). This is the first in a series of articles that takes a closer look at the art of potential contenders. Nominations voting ends January 8 and the Academy announces nominees January 15.]

One of Inherent Vice’s most satisfying scenes is one of its simplest and most quietly absurd. The ever-wayward P.I. Doc Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix) and his attorney-in-spirit, if not quite in practicality, Sauncho Smilax, Esq. (Benicio del Toro), are sitting at a police desk opposite of its owner, Det. “Bigfoot” Bjornsen (Josh Brolin). And that, apart from the fabulously loopy dialogue that suggests hard-boiled banter run through the cumulative filters of Preston Sturges and Dr. Seuss, is the extent of the set-up. It’s the two-shot of Phoenix and del Toro at their simultaneously most self-amused and bedraggled that sells the scene. It feels right. So right, in fact, that you search your mind to recall the last film that paired the stars, only to surprise yourself by coming up empty.

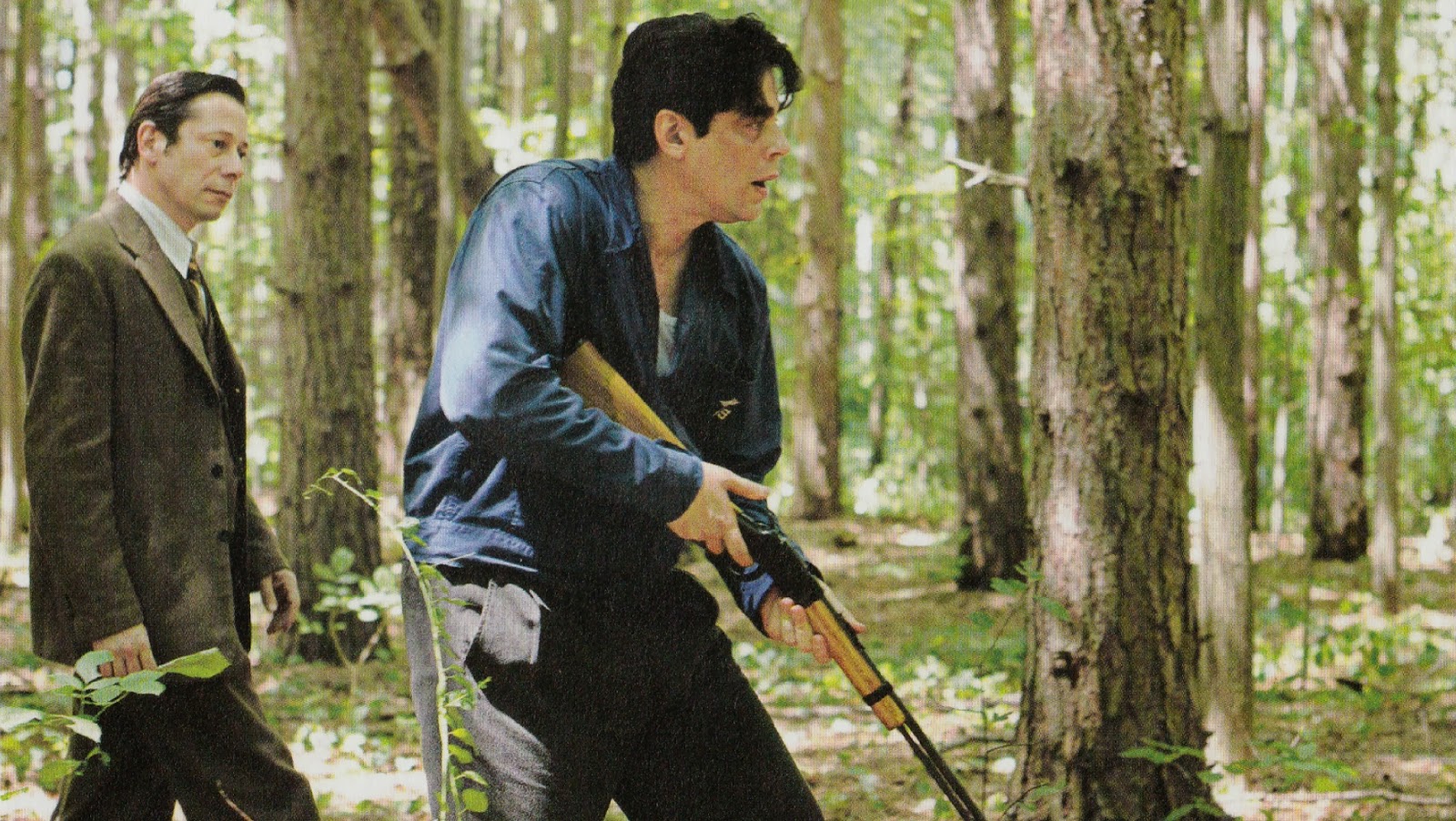

This is Phoenix and del Toro’s first scene together, though déjà vu is triggered by the wealth of other associations that float in and out of their exchange with Brolin. Phoenix has played the wily but emotionally inept outcast corned into a tough situation too many times to count, and del Toro’s role suggests an intuitive fusion of the gonzo comedy he played in The Usual Suspects and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas with the world-weariness he mined in Traffic. There’s also the actors’ chemistry with one another, which is rich and immediately connotative of a shared past. This last association is intensified by the year Phoenix and del Toro have just had creatively, both together, in their handful of Inherent Vice duets, and respectively apart, with Inherent Vice (which is predominantly a duet between Phoenix and director Paul Thomas Anderson) and The Immigrant for Phoenix, and with Jimmy P: Psychotherapy of a Plains Indian and Escobar: Paradise Lost for del Toro.

Seeing all of these films close together reveals how uniquely simpatico Phoenix and del Toro are as screen presences. “Self-amused and bedraggled” is the first step to describing the place where their talents intersect. They both often exude a sense of depression that’s understatedly infused with wryness. Whenever either actor allows one of their characters to smile, that smile is certain to somehow feel both cheap and hard-won at once. Their smiles are ironic, undermined with the tension in their eyes, or, more specifically, understood as physical attempts at irony that are compromised by the characters’ evident exasperation, alienation, sadness and hopelessness. Both actors are inherently funny men, and that’s pivotal to their ability to plumb excessive detachment without losing the audience. They use their humor to contain their obsessiveness within an examination of everyday theater as a necessity for getting by in life’s casual encounters.

In Inherent Vice, del Toro, the funnier of the two, challenges Phoenix in a fashion that’s only rivaled in the film by Martin Short. In that scene in the police station, del Toro lands a striking effect that’s true to the spirit of author Thomas Pynchon while feeling pointedly arbitrarily improvised, which is, partially, what the spirit of what Pynchon is probably about to begin with. Threatened, Doc reminds Sauncho that he’s Sauncho’s client, to which the attorney responds with “Clients pay me for work, Doc. Clients pay me for work, Doc.” It’s the lack of a beat, to punctuate the unexpectedly stylized repetition, that scores the laugh, coupled with a flash of exasperation that registers in del Toro’s eyes, signaling that this is an old routine between Sauncho and Doc. It’s a classic moment, and a key moment, early in the film, that signals to the audience that anything is capable of happening in this particular picture.

Phoenix’s performances, both in Inherent Vice and The Immigrant, are trickier, as both continually require the actor to be upstaged quite deliberately by one or more co-stars. In the above police station scene, Doc weathers the flamboyantly amusing gestures of both Sauncho and “Bigfoot” in a manner similar to the way he weathers all the actions of all the other characters, almost all of which are played by walk-on guest stars: with a blinkered, delayed reaction that conveys both intense self-absorption and befuddled longing. Doc’s a stoner, but Phoenix doesn’t go in for the usual lovable stoner clichés: he renders Doc authentically, rather than fleetingly, inaccessible.

Seeing the film for the first time, I thought that Anderson allowed Phoenix to play too comfortably into his specialty of the lead who is a world upon himself, unreachable by others, blocked, in the case of this character, by a haze of bong smoke. But Phoenix allows you to see the weight of Doc’s loneliness and disenchantment, which is synonymous with the great American disenchantment that fuels the entire film. Doc seems overfed and underfed at once, puffed out, with big hairy cheeks reminiscent of John Belushi, yet reduced, often hidden by all of his defensive props (jacket, hat, glasses, mutton chops and so on). Phoenix spends much of the film curled up or bent over—he spent much of Anderson’s The Master contorted in a similar manner—suggesting a desire to escape within the confines of a setting that’s somewhat reminiscent of the character physicality plumbed by Joanna Hogg’s Exhibition. [Editor’s note: Exhibition is not available for Fandor viewing until Friday, January 9.]

All of this informs how Phoenix will allow Doc to respond to Sauncho or “Bigfoot.” In regard to Sauncho, Doc lets him score the punchline, displaying a look of knowing oblivion, which will occasionally be interrupted by flashes of surprisingly direct and fleet intelligence. (This intelligence is generally on greater display opposite of “Bigfoot”.) Phoenix is revealing to us, step by step, why so many people enlist Doc as their private detective despite his apparent lack of control over anything that happens to him: he’s a warm and passive case worker, who can read people when he deigns to. Phoenix, Anderson, and Pynchon all understand that, in most films, the private eye is really a counselor or a therapist with a few melodramatic tropes tacked on for fashion.

Del Toro is also an artist occupied with self-absorption and loneliness, but he often achieves his effects in a manner that almost directly opposes Phoenix’s methods. The last word that could be applied to del Toro is “recessive,” and he never cedes a metaphorical tennis match to another actor in a scene with him. He’s an overpoweringly physical and charismatic performer. Del Toro’s two great instruments are his voice and his weight, both of which fluctuate to degrees that cinematically translate to commanding heaviness. That brief staccato flutter in the repetition of the “clients pay me” line is reminiscent of del Toro’s wonderful flamboyant grandstanding in The Usual Suspects, though he can also slow his vocal deliveries down so much as to nearly appear to chew on each and every word he speaks.

This is the strategy that memorably characterizes his terrific performances in Savages and particularly Jimmy P, the latter representing a case of effective over-under-acting. Co-star Mathieu Amalric gets to perform the inspirationally hyperkinetic comedy, but del Toro owns the movie, informing his voice with a subtle Native American inflection that emphasizes hesitation with English as a borrowed language. The actor celebrates the tactility of syllables as poetic stopping points; the way he says the word “Blackfoot,” hitting both sounds with hard solitary vulnerability, is worth the price of admission itself.

Come to think of it, Phoenix tries a similar vocal effect in The Immigrant, fashioning his most explicit acknowledgement of role-play as a quest for emotional governance. Marion Cotillard’s Ewa occupies the film’s center ring, but Phoenix’s Bruno gradually comes to command our, and Ewa’s, sympathy as he evolves from a sleaze to a stymied arrested development case not all that dissimilar from the character Phoenix played for director James Gray in Two Lovers. It would be easy to take Phoenix’s performance as Bruno as awkward and self-conscious, especially in the climactic scene, which calls for him to almost directly ape Brando’s tilted facial mannerisms from On the Waterfront, but that dismissal is ultimately short-sighted.

Phoenix isn’t a bad actor but a great actor playing a bad one, a low-level criminal on the off-off-off-off Broadway theatrical fringes who’s stirred, by his longing for Ewa, to attempt romantic gestures that aren’t among his repertoire. Phoenix makes consistent subtle comedy of Bruno’s disingenuous attempts at chivalry, such as the halting vocal fashion he adopts for negotiating payment for Ewa’s sexual services to his johns, only to suddenly flip that comedy into a tragic acknowledgement of feeling that’s so immense it dwarfs the human ability to communicate it. The climactic scene, before Ewa is to finally leave New York City with her sister, calls for Phoenix to do much of his usual bending and contorting, but with bold facial twists and purposefully contrived line deliveries (most memorably when Bruno likens his heart to poison) that signal intense self-loathing and emotional constipation. The poignancy of the scene is defined by its purposeful blurring of the lines: Phoenix lets his work show, puts quotation marks on it and breaks your heart anyway, by acknowledging the protective limitations of said quote marks.

Phoenix and del Toro both play, in scene after scene, in movie after movie, with the elastic possibilities of melodrama. They are both performers who like to go real big and heavy, and they’re both talented and cagey enough to recognize the little fillips of playful self-reflexivity that allow one to go much farther into the cosmos of bold, symbolic acting without losing the audience’s trust in their characters’ ultimate humanity. (That might be the single most influential tenant of Brando’s legacy.) Bruno’s final scene wouldn’t work without the coy Dickensian bits of comedy that precede it and prepare for it. Jimmy Picard might be a stereotypically “stoic” Native American if del Toro didn’t allow his intelligence and his desire to connect to show in his speech patterns. Escobar: Paradise Lost, an otherwise pitiful movie, wouldn’t be anything without that great black comedy scene where del Toro wears his contemptuous mortal flippancy with hilarious obviousness while casually drafting an order for a hit while ostensibly interviewing his niece’s potential suitor.

Both actors have great lined pained faces, and they seem to understand what those faces are best suited for: roles that plumb, time and again, the uncertainties, delusions and hypocrisies that reside underneath the theoretically democratic American Dream. They are drawn to tragic schemers or dreamers who test their abilities to go as simultaneously broad and specific as possible. This history, these obsessions, color the electricity that sparks off of Phoenix and del Toro’s brief Inherent Vice scenes. Del Toro, with his wounded in-the-know energy, was born to compliment Phoenix’s nervous estrangement. Together these energies somehow suggest a curious and tormented hope that can’t quite allow itself to tumble into the ideological void of nihilism.