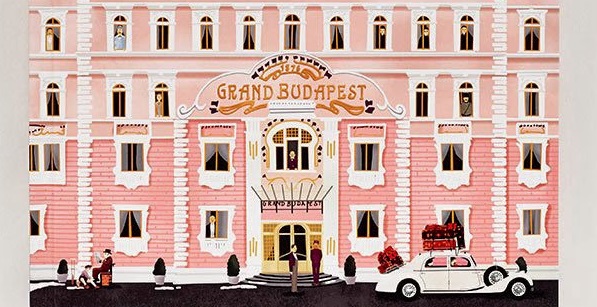

A big winner in the fine-points-of-film categories of the 2015 Oscars, The Grand Budapest Hotel is certainly worth a second, third or fourth look, and The Wes Anderson Collection: The Grand Budapest Hotel offers that and more. Published by Abrams, this is the much-anticipated follow-up to The Wes Anderson Collection, an immaculately designed, thoughtfully written compendium of all things Wes Anderson penned by RogerEbert.com editor-in-chief and New York Magazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz. Although this book is smaller in scope, Seitz and company’s latest is another gem, lovingly adorned with long-form interviews with Anderson and the cast and sumptuous stills from behind the scenes of the film. I got to speak with Matt about the passion project this past month.

Samuel Fragoso: You’ve watched The Grand Budapest probably more than most. What are some things you’ve discovered upon repeated viewings?

Matt Zoller Seitz: Well every time I see it I discover something new. That’s especially frustrating now that the book is actually out. Just last night I watched the movie again, they had a screening at the Nitehawk Cinema in Brooklyn, and there were a couple of different points where I turned to my editor and said, ‘I’m so mad at myself for not putting that in the book.’ One of them was the number of shots of an actual train in the movie. I make a big deal of how he fakes a train with sets and dollies. There were three shots of actual trains in the movie.

Fragoso: You probably could’ve turned into an essay.

Seitz: Probably so. But that’s the sort of anal-retentive thing I would’ve like to put in the book. It’s what Wes Anderson fans would like to know.

Fragoso: When did you first meet Wes Anderson?

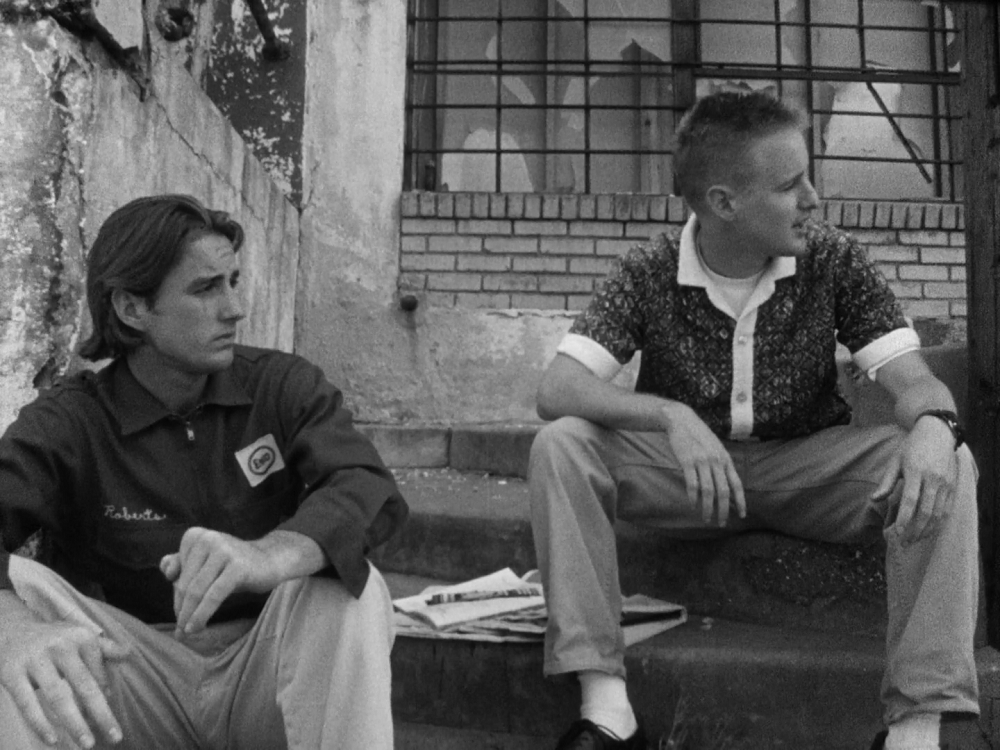

Seitz: I met him after he had made Bottle Rocket, the short film. Which is black and white, maybe twelve minutes long. It was on a program of short films that played at the USA Film Festival in Dallas. I was one of these crazy, completist type people who wanted to review every single thing that was in the festival, plowing my way through stacks and stacks of cassettes. I was really quite taken with Bottle Rocket and soon after, I discovered that the filmmakers were based in Dallas. Wes is from Houston, but Owen and Luke Wilson are long time Dallas people. So I thought, ‘Oh I should do a little piece on them because they’re talented and they’re going places.’ Not too long after that they received money from Columbia to turn it into a feature film and I ended up doing a cover story for The Dallas Observer where I followed the making of that film from start to finish.

Fragoso: How much has your relationships with Wes changed since writing that story twenty years ago?

Seitz: Well, I think it has stayed basically the same. It was always an intellectually based association. When I talk to him we’re usually talking about film and music and plays. It’s not a, ‘Hey how’s the wife?’ situation. He’s a guy who travels a lot. He doesn’t live in one place for more than three-to-six months if he can help it. And he wants to see as much of the world as he possibly can and actually live there. He’s on a grand adventure.

Fragoso: In what ways do you think his work has evolved since Bottle Rocket?

Seitz: He’s certainly become more confident and more ambitious and more precise. Bottle Rocket has a raggedy charm to it that appeals to a lot of people. His early films are more about taking the real world and making it fanciful. Whereas once he gets to Fantastic Mr. Fox he is really using the real world [aspects] as if they were components in a fantasy or science-fiction movie. In other words, he’s treating reality like it’s raw material, which is a step-up from just adding something to reality or changing it a little bit through how you shoot it. And in fact, the more I think about it the more I would say the most important film in his development is probably the Fantastic Mr. Fox. People forget that because of the order of the films they think of Fantastic Mr. Fox as coming after The Darjeeling Limited. But he started work on the Fantastic Mr. Fox right after Life Aquatic, and it took him longer to finish because it was an animated film.

Fragoso: Do you remember the first time an Anderson film floored you?

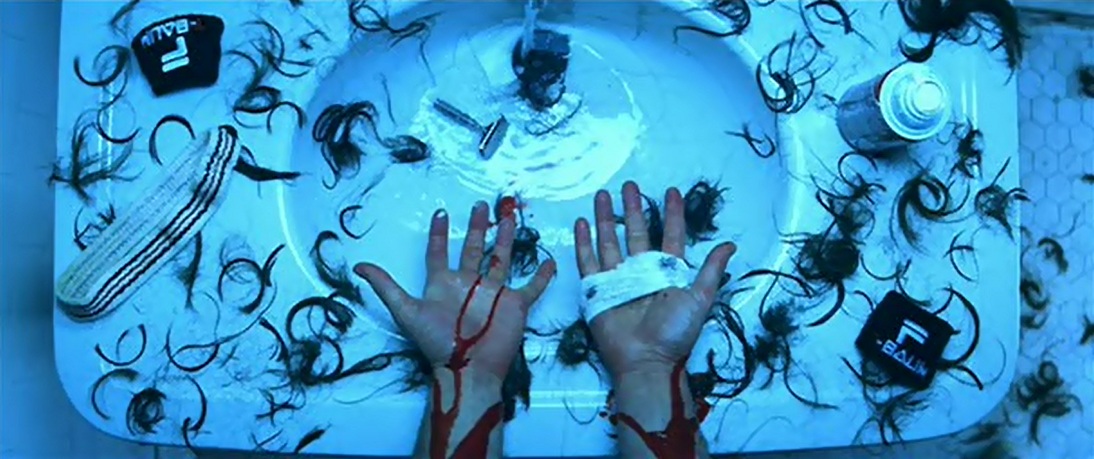

Seitz: The end of Bottle Rocket. The climax where the cops are chasing Dignan through the warehouse and then they beat the crap out of him. And it really looks like the cops are beating the guy up. It doesn’t look like the type of thing you’d see in a lighthearted comedy, strongly influenced by the comic strips of Charles Schulz and the early films of Francois Truffaut. At the very end of that movie, when Dignan walks back in prison and it shifts in slow motion and there’s fear in his eyes—that’s when I knew that there was something to Wes besides whimsicality. There were always glimmers of it, but that made it official. Then he gets to Rushmore and he’s got the hero getting punched out and cutting a man’s brakes and that entire montage where Max and Mr. Bloom are actually trying to kill each other. There’s also just a lot of pain in that movie. And then you get to The Royal Tenenbaums and that’s where he takes off. I love The Beatles so I compare everything to them, but it’s like the moment in The Beatles’ career where they released Sgt. Pepper and everybody went, ‘Holy shit. Something really major is happening here. We’re all going to have to accommodate it otherwise we’re not going to be able to listen to The Beatles anymore.’ And for me, in Wes Anderson’s work, that’s the moment when Richie cuts his wrists.

Fragoso: Is there an amusing anecdote that you have with spending time on set with Wes?

Seitz: One memory from the Bottle Rocket shoot does standout for me. And that is Wes shooting the scene where Anthony is having a conversation with this young woman by the side of a swimming pool. Meanwhile, Bob Mapplethorpe and his brother, Future Man, are fighting in the house. I was there when they shot that scene, and he staged that entire fight so that you see it through the windows of the house. They did it that way, from two or three different angles, but the camera was always seeing the fight through the windows of the house from a great distance. When it was done he said, ‘Alright, I think we got it.’ And I asked, ‘So now are you going to go into the house and shoot the fight?’ And he said, ‘No.’ He was twenty-five years old.

Fragoso: Do you find it difficult separating the man from the art when watching his films?

Seitz: Hmm…I never officially reviewed any movie he’s ever made, where I’m evaluating it for the reader and recommending it or not recommending it. I’ve known him for so long and I don’t think it would be right. I have written critical essays about Anderson’s films, which are in the book, and I’ll publish them at RogerEbert.com where I’ll always say, ‘This is an excerpt from my book.’ And anybody who reads the books knows, these books are by somebody who has an association with Wes that is somewhat different the typical relationship between the critic and the filmmaker. I try to be as careful as I can with that. I think it’s highly unlikely that I’m going to have an allergic negative reaction to anything Wes does as a filmmaker because I have known him for so long and I feel like we have so much in common in terms of our tastes. So when you’re looking at these books you’re not looking at a critical or biographical study by somebody who’s coming at it from a hermetically sealed point of view. This is from somebody who is in there and is compromised in a really basic way.