Shin Godzilla, the first new Japanese Godzilla film in twelve years, stomped into the record books as Japan’s top moneymaking live-action film of 2016, and the highest grossing Godzilla film ever, but it practically snuck into American theaters last week, staking out one or two showings a day in urban multiplexes with practically no advertising and no advance screenings. American audiences sought it out and sold out showings nonetheless, inspiring stateside distributor Funimation to expand its release to more screens and showtimes.

What makes this all the more surprising is that it’s counter to everything we associate with a classic Godzilla movie. And I don’t mean the inevitable shift from suitmation (the man in a suit stomping through elaborate miniature cityscapes) to motion capture and CGI. The third Japanese reboot of the series opens with an echo of the original 1954 Godzilla, on the mystery of an abandoned boat in open water, but otherwise it wipes the slate clean and treats this as the first ever encounter with a giant creature on a tear through Tokyo. Not what you expect from a film whose title translates roughly to New Godzilla—according to the film’s executive producer Akihiro Yamauchi, “Shin” can stand for “new,” “true,” and “god”—and alternately has been called Godzilla Resurgence by Toho. As far as this film is concerned, it isn’t a return. This is first contact.

But that’s not what makes it so unusual. The spectacle is there, with Godzilla evolving from a massive wormlike sea creature crawling through Tokyo to the more dinosaur-like lizard king in the first act, sprouting legs and arms and spiny dorsal fins that, eventually, shoot laser beams powered by its atomic-fusion heart. But this film is more invested in how the government responds to the crisis. More to the point, it is about how government actually works.

It is, to put it simply, unlike any other Godzilla film made before. This is to say, it is a film that reflects the culture of its time, just as the original 1954 Godzilla reflected its own culture. Born in the wake of Hiroshima and America’s nuclear tests in the Pacific, Godzilla entered the international scene as an avenging devil rising from the radioactive ashes of the atomic age. It was a metaphor that Japanese audiences understood all too well. But there was also another, more immediate inspiration: the Bikini Atoll atomic tests, and the Japanese fishing boat Daigo Fukuryu Maru, which drifted into contaminated waters in early 1954. The crew was exposed to nuclear fallout and suffered severe burns and radiation sickness. The opening scenes of Godzilla evoke the event directly. For American audiences, it’s an eerie prologue, but for Japanese audiences, it played upon very real fears and set the tone for a dark nuclear parable in a solemn key. Director Ishiro Honda (a former assistant to Akira Kurosawa) renders Tokyo in the manner of a neorealist film rather than a splashy spectacle, and Godzilla’s devastating rampage and radioactive breath leave behind thousands of casualties and a city aflame, recalling nothing less than the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Victory comes at a terrible cost, by way of a weapon so horrible it kills everything within its reach. You can’t miss the nuclear parable, though the Americanized version that played stateside tried hard to play it down.

While Godzilla was born as a devastating force majeure, his transformation began early on. The films went color and emphasized the spectacle over the darkness; soon enough the rampaging monster was Tokyo’s savior, defender of Earth from alien invaders and robot doppelgangers, and superstar player in mad monster parties and giant-creature turf wars. Perhaps it better expressed the shift from Japan’s post-war struggle of rebuilding and redefining itself to the prosperity of the sixties, which saw a booming economic growth and the beginning of Japan as an electronics and technology powerhouse.

Or maybe it was the inevitable evolution of a popular series embraced by kids and merchandized into a cottage industry. Regardless, the first wave of Godzilla films, called the Showa series, ended with The Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975), a film featuring a giant mechanical Robotzilla, alien invaders who look like refugees from a low-budget Planet of the Apes knock-off, mad scientists, and spies. Apparently embarrassed over his slide from modern atomic Golem with mythic dimensions to star of campy monster-mash fantasies, Godzilla took a temporary retirement and waded back into the sea for a ten-year hibernation.

The second wave, the Heisei series, launched in 1984 (the thirtieth anniversary of the original film) with The Return of Godzilla, as much a direct sequel to Godzilla as a revisionist remake. It swept away the past thirty years of campy sequels and returned the Big G to the awe and solemn grandeur of the mighty first feature (to stand out against the skyscrapers of the modern Tokyo skyline, he was supersized to a towering 260 feet tall), resituated the disaster in a more global context, and put the modern atomic age front and center. Here Godzilla destroys a Soviet nuclear submarine in the Pacific, and, five years after the Three Mile Island accident, attacks a Japanese nuclear power plant. The Japanese Prime Minister stands up to demands by the U.S. and the Soviet Union to use nuclear weapons on the creature. Cold War tensions also cast a chill over the film: The Soviets pre-emptively launch a missile at Japan, and the U.S., now the latter’s ally, intervenes to save it from another atomic strike. Though not a big hit in Japan, Return was successful enough to launch a new series which, again, transformed Godzilla from angry atomic demon to self-appointed monster cop protecting the island nation from a roll call of old adversaries revived for rematches—concluding at last with the knockdown, drag-out fortieth-anniversary match Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995).

The third wave, the Millennium series, can be seen at least in part a response to Roland Emmerich’s misguided attempt to bring the Big G stateside with a CGI makeover in the 1998 Godzilla, a film more indebted to Jurassic Park than to the Japanese franchise. Godzilla 2000 (1999) once again swept away a generation of sequels to pose the first return of the lizard king since the original 1954 Godzilla. But this is no atomic fable or modern metaphor; this is pure matinee kaiju smackdown, with Japan’s favorite atomic lizard now recognized as something between a force of nature and a national spirit protector, and an alien invader set on mining Godzilla’s preternatural regenerative abilities. The series continued in the same mode, embracing the spectacle and the escapism all the way through to the fiftieth-anniversary film Godzilla: Final Wars (2004)—the twenty-ninth film in the franchise, the final film in the Millennium cycle, and the last Japanese Godzilla film for over a decade. It was also the first Godzilla film in decades to embrace that early “history,” bringing back all the old monsters for one last fight, and for good measure tossing in an alien invasion force, a team of Power Ranger-like mutants, and a hilarious parody of Emmerich’s CGI lizard. This was Godzilla as a pure pop culture icon.

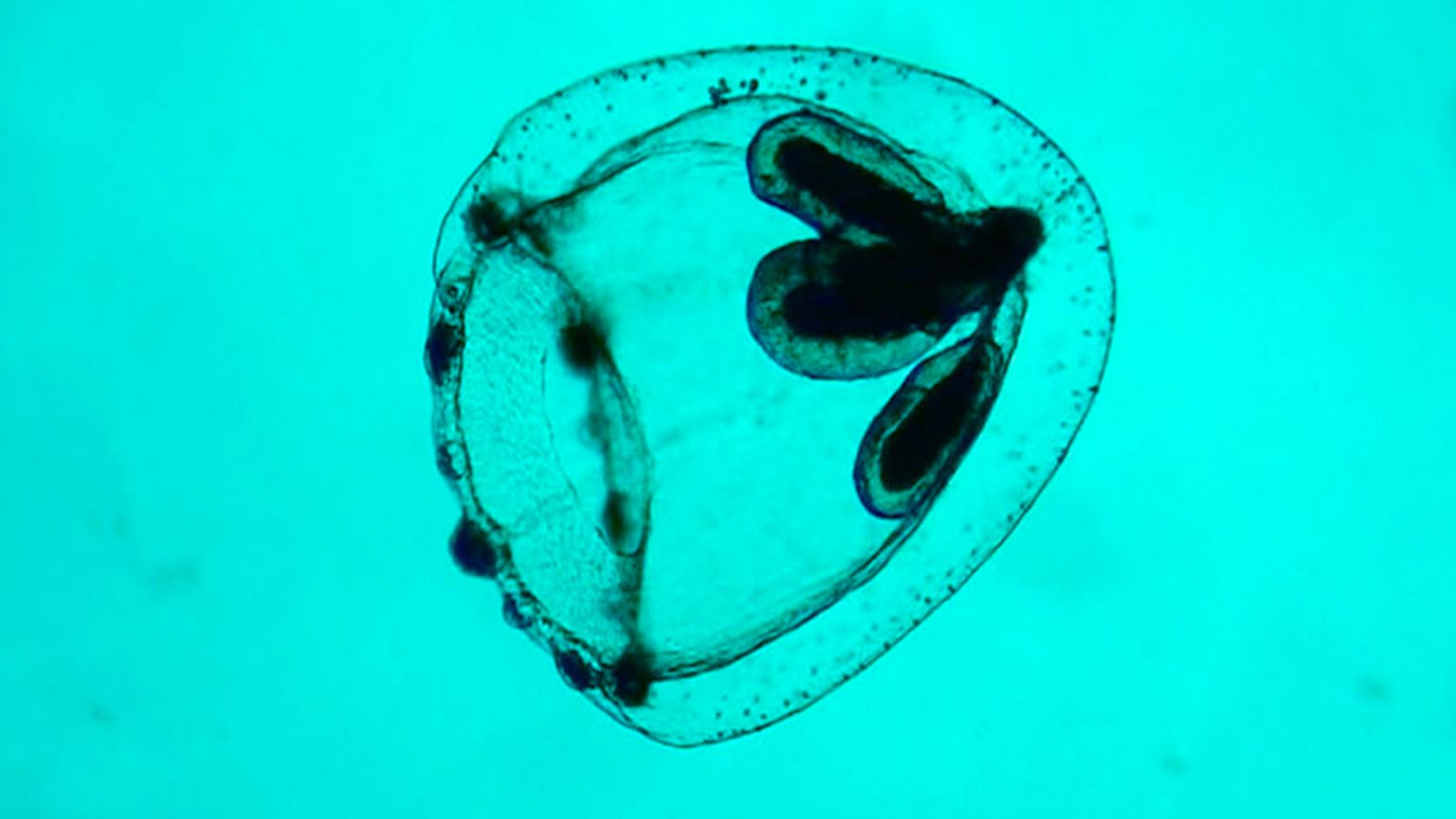

Shin Godzilla, written and co-directed by Hideaki Anno, creator of the Neon Genesis Evangelion anime series, is Toho’s first Godzilla film in twelve years, and there is nothing campy or comic about it. Though born of the atomic age, this Godzilla is the result of radioactive waste dumped illegally in the ocean, where it has seeped out and supercharged the evolution of a prehistoric holdover roused from the ocean floor. His rampage is not a metaphor for the atomic bomb but an evocation of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, swamping Tokyo with a tsunami-like wave as he makes landfall, and leaving a trail of crushed and splintered buildings and bridges. In a nod to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, he poisons his path with a lingering dose of radiation that leaves the area uninhabitable. And it all takes place in the twenty-first century of globalism, where the U.N. claims jurisdiction, and Russia and China demand a nuclear option to stop the threat from spreading to the rest of the world. In this context, Japan’s special relationship with the U.S. comes into play, with the two nations quietly trading information like they’re making a secret spy swap. Not that this is some altruistic gesture, mind you. The U.S. would rather not share the discoveries of Godzilla’s organic fusion with rival powers, so a private deal in their interest.

All of which gives the human side of the drama both an urgency and a special charge. More than half of the film consists of politicians, bureaucrats, and military leaders debating issues of policy and jurisdiction, along with the basic questions: What is this thing? Where did it come from? How can we stop it? This is a crisis unfolding in real-time, and while there is a dose of satire to the bureaucratic tangle and old-school politicians ridiculing theories that fall outside of their limited experience, there’s also an acknowledgment of how and why government works as it does. You’d think that would make for a dull film—and at times it is awfully confusing—but Anno isn’t interested in documentary realism. He creates a geek squad of mavericks, nerds, outcasts, and free-thinking visionaries to research and brainstorm options: Plan B for a government that can’t think outside the box of military aggression. Rapid-fire cutting adds to the urgency, while the stumbling government response to an unforeseen and unfathomable disaster humanizes the ordeal in ways you’d never expect.

This isn’t a story of a couple of rogue visionaries go directly to the prime minister and take the reins of a nation’s military to save the day. It’s about a bureaucratic system learning to communicate and coordinate in the midst of chaos, like a battleship course-correcting as new orders are countermanded every few minutes. It makes for a Godzilla film like we’ve seen before—for better and for worse, but mostly for the world, we live in today.