Blind spots: we’ve all got them. How readily we admit to never having seen a particular director’s work—or any films from a specific movement or historical period—might depend on our company, of course. But cinephilic virginity can be a source of others’ envy as much as it is one’s self-imposed embarrassment. If discovering great cinema is the aim of our game, then the more virginal the better—for a field reduced to mud by others can still be ripe untouched terrain for someone keen to get in on the fun.

I’ve felt late to the party twice recently. The first was to Bertrand Tavernier, the French filmmaker to whom Lecce’s Festival del Cinema Europeo dedicated a small retrospective in March this year. Tavernier is far from a slept-on gem at this stage in his forty-year feature-making career (he made two shorter films in the early 1960s before a full-length debut in 1974), and so I was keen to take the southern Italian festival’s tribute as an opportunity to do some catching up—especially with the director present.

In the end, though, I was thwarted by language. No Francophone, and unable to read Italian, my first entry into Tavernier’s oeuvre had to wait: no English subtitles. Compounding matters, a month later I missed two chances at Crossing Europe Film Festival (in Linz, Austria) to catch his latest film, Quai d’Orsay (2013)—owing to too tight a viewing schedule. My eventual and belated delve into Tavernier came in the form of a one-two punch here on Fandor, which hosts two of his films: Let Joy Reign Supreme (1975) and Life and Nothing But (1989). The former title was only Tavernier’s second feature, following The Watchmaker of St. Paul (1974), and saw the director working once again with that film’s two principal leads, Philippe Noiret and Jean Rochefort.

In the film, which is set in 1719 France, Noiret plays Philippe II, Duke of Orléans—the real-life regent for pre-teen heir Louis VI between 1715 and 1723. Rochefort plays Guillaume Dubois, a wily and ambitious priest who in the film hopes to become an archbishop (he later became a cardinal), and who plays an instrumental role in handling a small anti-tax uprising in Brittany. In Life and Nothing But, Noiret—who had appeared in three more of Tavernier’s eight features since Let Joy Reign Supreme—plays Dellaplane, a French Major tasked in 1920 with investigating the identities of unknown dead soldiers who falls for Irène de Courtil (Sabine Azéma), a woman searching for her missing husband on the torn-up pastures of World War I.

Though their stories take place two centuries apart, and though their own productions were separated by 14 years, both of these impressive films have common characteristics. Each is a period piece whose costume and set design seem to serve character and plot rather than vice versa, and whose directorial style tends to rather than competes with content. Similarly, each film boasts narrative concision and storytelling conviction—funny observations to make, perhaps, of films running for 114 minutes (Supreme) and 130 (Life), but the sophistication and breadth of each script (interweaving class conflicts and social crises with emotional tumult and psychological flux) is remarkable.

There seems to be something punchy rather than beautiful about Tavernier’s period films. Both movies go about their status of “prestige picture” unassumingly rather than snootily. Both have a solid and precise mise-en-scène as opposed to a cluttered or showy one. And both are functionally rather than self-consciously cinematic. Unsentimental in feel and yet deeply human, their narratives’ ironies stem from patient build-ups and the complexities of history itself rather than any forced storytelling or directorial sleights-of-hand.

All of which might be to say that Tavernier—who came through the Cahier du cinéma ranks as a film critic, but who only matured into directing after Godard, at least, had burned himself out and shifted away from making films for other people—is an intellectual in the truest, most complimentary sense of the term. Here is a filmmaker, it seems, who looks outward in order to reveal reality’s deeper currents, rather than one who looks inward in order to retreat from them with quips, gags and pretension.

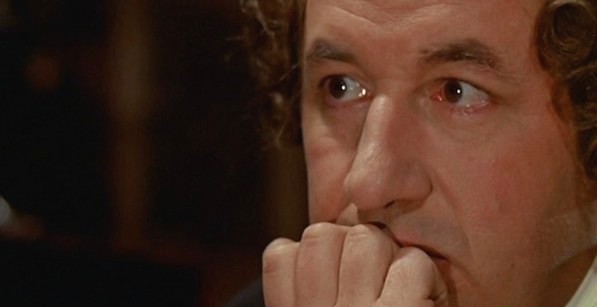

In watching both Let Joy Reign Supreme and Life and Nothing But, I’ve come to realize I’ve been sleeping on not one great artist, but two. I had previously remembered Philippe Noiret only from Cinema Paradiso (1989), in which he plays gentle cinema projectionist Alfredo in that film’s postwar segments (I don’t remember him in Hitchcock’s Topaz, and don’t remember much at all of Agnès Varda’s 1956 drama La Pointe Courte). There’s something similarly avuncular to both of the characters Noiret plays in Joy and Life—a quality that seems to be an extension of the late actor’s own general likability. Already into his forties by the time he came to work with Tavernier, the actor delivers lines with a nasally curtness and a piercing look, though any possible frostiness caused by this combination is offset by the slight surplus of skin beneath his chin and a like-it-or-lump-it brand of warmth.

Noiret is like that unmarried (or perhaps widowed) uncle, against whom young mischievous nephews team and pester into performing some card tricks—all the while secretly intrigued by his outward lack of affection because they sense, through every other adult relative’s behavior toward him, that he’s the one the family loves most. The Duke of Orléans and Major Dellaplane must both assume mantles that an unkind history thrusts upon them: one is regent for a young monarch at a time of absurdly pointed social contradictions, the other spends his days searching records of the first world war’s undocumented dead. Both characters are flawed, unremarkable heroes who try to make the most of difficult predicaments—and do so in vain.

Though he’s not noted as an especially versatile performer, Noiret, like the late James Gandolfini or a less chameleonic Toni Servillo, was one of those actors who brought his own palpable charms to each role. This isn’t to claim he wasn’t stretched: indeed, for actors of this ilk, the job itself is a challenge to be risen to—and Noiret did this with a seemingly dependable and indefatigable professionalism, notching up more than 100 appearances by the time he died, aged 76, of cancer in 2006. His was an undemonstrative kind of intelligence: hard-working, committed, loyal.

Romantic, in a word—and in these traits and others, one can see why he was the perfect foil for Tavernier. Look no further than that gesture forty-two minutes into Life and Nothing But, when the director gently but directly tracks in on his actor’s face, as his character parts company with a woman who’s gradually stealing his heart: as Dellaplane, Noiret looks away and back again with all the heartache of a prolonged and dormant boyhood.