[Editor’s note: This feature marks the seventh piece in an Orson Welles series celebrating the 100th anniversary of the filmmaker’s birth. See previously published pieces: “Orson Welles: The Enigmatic Independent, “The Orson Welles Bookshelf,” “Rosenbaum on Welles at 100” and “Schooled by Orson Welles: Roberto Perpignani,” “Orson Welles Goes Around the World” and others in the Keyframe archives. Meanwhile Wes Anderson and Noah Baumbach campaign for the completion of a Gary Graver-Orson Welles creation, The Other Side of the Wind.]

Gary Graver, the man who committed himself to serving as Orson Welles‘ cinematographer for the last fifteen years of his life, learned his trade on the battlefield—literally—as a cameraman in Vietnam. When his tour of duty was over, he took his skills to Los Angeles and landed work shooting a film for notorious cult director Al Adamson called Satan’s Sadists (1969), the first of over 200 productions. He shot cheap drive-in films for Roger Corman, Jim Wynorski, Fred Olen Ray and Adamson, second unit work on Enter the Dragon and Raiders of the Lost Ark, and directed horror films, documentaries, family comedies and even adult movies. And he was Welles’ cameraman on everything Welles made between 1970 until 1985, from F For Fake and Filming Othello to TV projects and pilots, commercials and unfinished films such as The Other Side of the Wind and The Dreamers.

I had the great pleasure of interviewing Gary Graver on two separate occasions. In 1998, while in Seattle to present some of his personal prints in a festival of Orson Welles films and fragments, he spent a couple of hours answering my questions about working with Welles. Five years later, in 2003, he returned for screening of Orson Welles’ F For Fake (1973) and I had the honor of conducting an onstage conversation and moderating an audience Q&A. He died three years later in 2006, after a long battle with cancer, but not before shooting another dozen or so pictures.

Here are a few of the great stories and experiences that Graver shared in those brief hours, including details on The Other Side of the Wind, which may finally be completed and released this year, more than forty years after it was begun.

Sean Axmaker: Tell me about how you met Orson Welles and began working with him.

Gary Graver: I had heard that Orson Welles was in town. Well, first of all I thought ‘I’m going to be a filmmaker.’ I was making my own pictures and then I started working as a cinematographer for the famous Al Adamson and I made a few pictures for him. But I thought as long as I’m going to make films, why not make films with Orson Welles? How am I going to meet him? Well he just happened to be in town and I called him on the telephone from Schwab’s Drug Store, the famous drug store in Hollywood. They put me right through to him at the Beverly Hills Hotel and he answered the phone. He said ‘Hello?’ I said ‘Mr. Welles?’ He said (gruffly) ‘Yes.’ I said ‘My name is Gary Graver, I’m an American cameraman,’ and introduced myself, and said ‘I’d like to work with you.’ And he said ‘Well I’m real busy right now. I’m leaving for New York. Give me your phone number.’ I gave him my number and *click*.

I drove home. As I was pulling into the driveway the phone was ringing. I ran in and I say ‘Hello,’ and he says ‘Gary, this is Orson Welles. Get over to the Beverly Hills Hotel right away.’ So I raced over there and went up to the bungalow very nervous and there he was. He said, ‘Sit down, have a cup of coffee,’ and we talked and I was very nervous. We were talking for about ten or fifteen minutes when all of a sudden he grabbed me by the back of the shirt and threw me down on the floor of his hotel room and pushed himself down on top of me. I had this heavy guy on top of me and I thought ‘Oh no, what the hell have I got myself in for now? What’s going on?’ He said ‘Sh! Quiet.’ I started to talk and he said ‘Quiet! Quiet!’ Finally time passed, a few minutes, and he said ‘Okay, get up.’ We sat up, I said ‘What was that all about?’ He said ‘The actress Ruth Gordon was out front of my window. If she saw me in here she’d want to come in here and talk and talk. I want to talk to you, so we just waited until she passed by.’ He said only one other cameraman in his whole career ever called him up and that was Gregg Toland, who said, ‘I’d like to shoot your movie, Citizen Kane,’ so he said it must be good luck.

So that was my introduction to Orson. He said that he had a project that he wanted to do and that he was going to New York to make a film called A Safe Place directed by Henry Jaglom. Orson left for New York and he called me a couple of times and when he came back he had me do a series of tests at the Beverly Hills Hotel to make sure I was a cameraman. We hit off just like that because I knew, watching his personality on the screen and the way he made pictures, I knew that if I met him we’d be friends. And we were. So shortly after his return from New York we started shooting The Other Side of the Wind with myself and Joe McBride and Peter Bogdanovich.

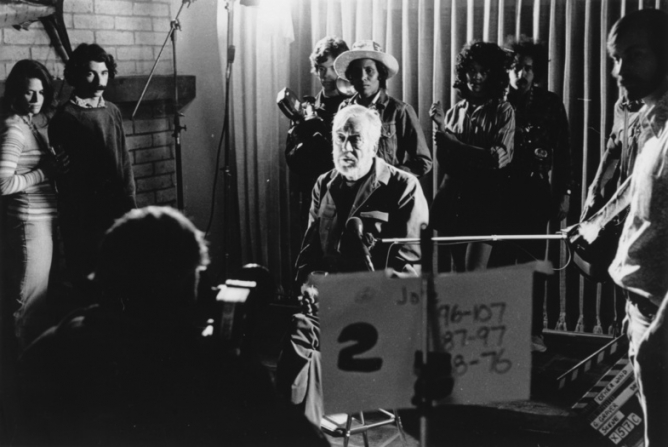

We started shooting in rented houses. We rented big mansions and shot in there and then we started shooting on locations, we started building sets, shooting on the back lot of MGM. We worked for four months, seven days a week. I wasn’t ready for that. Seven days… the only reason I could get a day off was if I said I didn’t feel good or something, and then he didn’t want you around if you were sick or anything. But I couldn’t keep my crew together for seven days, so we interchanged people all the time. We shot over a period of four years, off and on. Not constantly because I did a lot of other pictures within that time, and so did Orson, but in those main years of the early seventies we did The Other Side of the Wind.

Axmaker: The cast was mostly friends and acquaintances of Welles. Did they basically volunteer for it?

Graver: Anyone would act in a picture with Orson. He wanted John Huston for the lead. He saw people a lot on television that he liked. He liked Rich Little, an impressionist who’d never made a movie, and he cast him as one of the leads, but when he took he was replaced by Peter Bogdanovich. Most of the cast were Orson’s cronies and friends: Mercedes McCambridge, Paul Stewart, Norman Foster. And then we cast some people I knew, actors I’d worked with in some of the younger parts, and then Orson elicited the cameo bits of Dennis Hopper and Curtis Harrington and Paul Mazursky and Henry Jaglom and various other people to play the new directors. Do you know the book Raging Bulls and Easy Riders [by Peter Byskind]? That’s what this scene is, that’s what this movie is about. The changing of the guard, the old director Huston finishing up his Hollywood tenure and the new directors coming up and a kind of a wild and crazy time of the hippie era and the changing scene in film. It was a Screen Actors Guild picture, everyone got paid, though I believe everyone probably worked for scale like they do for Woody Allen. That’s how it was put together.

Axmaker: It was during this time that F For Fake came his way.

Graver: Yes, we were going to do something on The Other Side of the Wind and all of a sudden, this F For Fake thing came up. Orson had seen and had met François Reichenbach, a French documentary cameraman, filmmaker and director, he had a lot of footage on Clifford Irving and Elmyr de Hory. Irving had done a book called Fake! about de Hory, a fake painter who had faked Picassos, Matisses, etc… Reichenbach had a lot of footage, it was not really edited, not finished or anything, and Orson got involved in it and got me involved. The documentary stuff was shot in 16mm and then we got the 35mm equipment and started shooting F For Fake [when it was revealed that] Clifford Irving was a fraud. Irving had written a book about Howard Hughes and said that he had met Howard Hughes in the pyramids in Mexico, which was a lie, a fake. So then our story became about that and as the newspaper headlines were coming out every day our movie was being made. And then Orson tagged the story of Picasso on the ending, which was another fake.

F For Fake was started in ’72 and you’re looking at the crew right here. Me. There was no crew. Orson found out that I could set the lights, run the camera, I had this Nagra sound machine there, I got cue cards up here, I built the sets, everything. And when I was in F For Fake, Orson would run the camera. I played a newscaster. High pitched voice like a Hollywood Jimmy Fiddler-type guy. F For Fake was finished, completed, and in theaters within a year. I toured with it in America in the major cities, and it played art houses for about a week or two everywhere and disappeared. So it was not like an unfinished work that dwindled on, it was done rather quickly.

Axmaker: All this time, you were essentially on call for Orson?

Graver: Yes. Luckily I had a good income. I didn’t charge Orson any money, so I worked the first year really for free, except if he got a job. The situation was, if he got a job doing some narration or talking head, I had to be the cameraman and I got paid for that. We had an agreement between us that, if I got a job, I’d come to him and say, ‘Orson, I’ve got a job doing this or that or some Corman movie.’ And then says, ‘Well, yeah, I don’t need you right now, go ahead and do it.’ I went from Al Adamson to Orson Welles, quickly. Al would ask me to shoot something and I’d say, ‘Orson, I’ve got a chance to work with Al Adamsom,’ and he’d say, ‘Who?’ But sometimes I had a chance to do a picture and he’d say, ‘No, we’ve got to work Gary. You can’t do it.’

I counted them, we did about 15 projects together. We did a magic show, we did the features Filming Othello, which is finished for German television to accompany Othello, and Filming The Trial, which no one’s ever seen, but they put it together in Germany recently [it has since screened at the Munich Film Museum]. Everything that Orson made in that period, he left to his girlfriend/companion, Oja Kodar, and co-writer, co-director, and everything else, the love of his life. So she got all the stuff that we did and I saved everything that I could that she didn’t have.

Orson was always doing four or five things at the same time. During the shooting of F for Fake, I came to the studio and Orson had a whole bunch of pots and pans and food out and I said, ‘What’s that?’ and he says, ‘The Food Show! The Cooking Show!’ like I was supposed to know I’m doing a cooking show. He never mentioned it before. He wanted to host a cooking show.

We did a series called Orson Welles’ Great Mysteries for English television in London. We shot that on the F for Fake set. Every week we shot. He did the introductions, the middle and the end and then we’d send the footage off the London to put in the TV series. Orson had a great time and a great reputation in the theatre, he was a huge success on the radio, of course, with War of the Worlds, and then he went to Hollywood and made Citizen Kane, but he could never conquer TV. He never got his own TV show. He came close when he made a pilot for Desilu [The Fountain of Youth in 1958], but no one bought it. Orson wanted to be the host of a talk show and the advice given him by his friends in Hollywood was that the three most popular guests at that time were Burt Reynolds, Angie Dickinson and the Muppets, so that’s what the show is. But it’s more than just a talk show, it’s got magic in it, it’s got film and video and stills, it’s a mixed thing. It’s 90 minutes long and it’s finished, but it was unsold.

Axmaker: What can you tell me about The Dreamers?

Graver: We shot The Dreamers at Orson’s house, which was a mini-Gone With the Wind place with big columns and a beautiful back yard. It was a mini-estate that he had. We’d just shoot for a few days and then nothing would go on for a long time because he’s written the script with Oja and they had the option, and every time the option would come up we’d have to shoot some more. It was intended as a twenty-minute promo reel to raise money. It was never intended to be finished. We knew we never had the money for that.

For The Dreamers, he wanted to keep building onto the house. We built a runway, we built another room, and he had to get lights. He said, ‘I need a light in the tree, I need some lights over there, I need some lights by the piano.’ I said, ‘Orson, this is going to be… I need another generator, I need more money, I need more crew, I need more people, I need more equipment, I need this and this and this.’ I warned him. Then we had our big night of shooting with all the generators, the lights and the crew and I gave him the bill. It was like $3,000 and he bellowed at me, ‘What in the world are you doing to me?! Gregg Toland would never have let me use this many lights!’ He said, ‘We did Citizen Kane, sometimes Gregg used one light.’ Well, I wasn’t going to tell him he couldn’t have his lights.

Axmaker: What kind of direction did he give you when you first started working with him? When you were setting up the camera, doing the lights, what kind of involvement did he have?

Graver: When he did Citizen Kane, Gregg Toland, the cinematographer, said in an interview that Orson was setting all the lights himself and telling people where to put the lights. Finally, someone told him, ‘You know, that’s the cameraman’s job.’ And Orson said, ‘Oh, really? Oh.’ And he stopped. But he knew exactly what he wanted, so when I started working with him, and I didn’t know his techniques, he would say, ‘Put a light up there, put a red gel on it’ or ‘Let’s put a 2k over there, some different lights, and get something down here.’ I let him do that. He did the lighting. He knew exactly what lens he wanted and where to put the camera and everything. So I was really, basically, the technician and I had to make sure the exposure was right and the light was right and it looked good so it was covered. But he knew what he wanted to do and as we got working more and more, I bought him this big chair we called the throne. And he’d take this chair out and he’d put it somewhere like this and he’d sit there. ‘Maybe the camera here. Give me a 40mm lens,’ or something like that. If I wanted to make a shot that I thought we should have, if Orson went to the bathroom, I’d come in and move the chair around somewhere. He came back and sat down and I got to make some shots that I wanted. And after a while he really trusted me, you know, and he would draw sketches and have me go out and shoot things. I’d bring them back and usually they were fine.

I was able to bring to him a style that was low overhead. I didn’t have a big crew and they didn’t make much money, seven or eight people instead of fifty or sixty people. So we would take our time. We weren’t rushing things. But actually, when we got to Other Side of the Wind, when we had John Huston and Edmund O’Brien and all these actors, we moved a lot faster. Orson did all of his own editing. Not splicing, you know, he’d have some hands to do that, but he called the shots on everything. In F for Fake, we have shots in the picture which are so short that there are no edge numbers in the negative. The negative cutter had to eyeball it. This was before MTV, before what they do now. Everything’s so fast, you get an image and it’s gone. This was a new style that he was trying to go for, unlike The Magnificent Ambersons, with all those long takes. Orson was not just a director. He was a producer, he was a writer and he brought theater and magic with him to film. And, of course, he was the foremost experimental filmmaker we have in this country. He was really an experimental filmmaker. He was always fiddling and trying new things and trying to stay ahead.

Orson worked seven days a week until he died. The day before he died, we were going to do Julius Caesar, with him playing every part himself, at UCLA. He didn’t feel good the morning of that shoot, so we didn’t shoot. And then he did The Merv Griffin Show that night and then died in his sleep.