During the short, cheesy, glorious heyday of what were termed (somewhat controversially) “blaxploitation” movies during the early-to-mid-seventies, most of the films falling in that category were urban crime thrillers in the mode of Shaft and Superfly. But there were exceptions, notably an entire subgenre that put a very particular spin on some familiar horror tropes, as you might guess from such titles as Blacula and Blackenstein. (There was even a black Exorcist, given the comparatively innocuous name Abby.) One ostensible “blaxploitation” horror from that era hardly fit in with its campy brethren, and has since acquired a measure of cult adulation. It’s Bill Gunn’s 1973 Ganja and Hess, which has remained relatively little-known–something likely to change now that it’s being paid a rather high-profile tribute: No less than Spike Lee has remade it as his Kickstarter-funded latest feature, Da Sweet Blood of Jesus.

Early reviews of Lee’s latest have complained it lacks the more complex sociopolitical and metaphorical layers of Gunn’s original. But Bill Gunn, a prolific playwright and occasional novelist, would have been pleased by the belated attention given this supremely idiosyncratic high point in a beleaguered film career. An ostensible “black vampire movie” that was anything but conventionally lurid or commercial, Ganja and Hess was horribly ill-treated in its scant original release. Yet it still suffered a better fate than the other two features Gunn directed, which are virtually impossible to see. Nor was he much luckier with the several films he wrote without directing: As early as 1971, he was already telling interviewers “I’ve liked every script I’ve ever written, and hated every script made from them.”

The handsome Philadelphia native, born in 1929, first made inroads as an actor. By 1954 he’d made his Broadway debut, and for he next decade or so enjoyed moderate success as a guest star on TV series in addition to his stage work. But his restless intelligence wasn’t satisfied by this solely interpretive role; his own plays began being produced in the late 1950s, his screenplays a decade later. (johnsonstring.com) The latter included Ján Kadár’s Bernard Malamud adaptation The Angel Levine and Hal Ashby’s sharp satire The Landlord.

Those were two of the more interesting American movies of 1970, even if Gunn was displeased by the liberties taken with his scripts. Not surprisingly, that same year he made his debut as writer-director. It was a perfect moment of entry, as the major studios were utterly panicked by rapidly changing audience tastes. They’d green-light just about any promising newcomer’s project, no matter how outré, so long as it didn’t cost a fortune.

Yet Stop was apparently more than they could handle, even in that wide-open creative era. Its perverse tale of two couples’ polyamorous, bisexual, color-blind and occasionally murderous involvements over a Puerto Rico weekend’s course was rated X. That wasn’t the kiss of mainstream death you might think, as back then “X’s” applied to such edgy, “adult” but decidedly non-pornographic films as Midnight Cowboy and A Clockwork Orange. Nevertheless, Stop was never released. It was screened for critics, and got a smattering of reviews that complemented its striking visual assurance (cinematographer Owen Roizman would be Oscar-nominated the next year for The French Connection) while finding its narrative content cold and cryptic.

Stop has since become one of the most-sought movies by people who (like me) are magnetized by inaccessibility; it’s as rare a bird as Jerry Lewis’ infamous, unseen The Day the Clown Cried. Warner Home Video’s recent claims that it would finally release the film to personal-order DVD have apparently run aground in the wake of newly unearthed rights-clearance problems. So whether you or I will ever live to see Stop remains an open question.

That must have been a huge disappointment for Gunn. Ergo he surely embraced the very indie budget and production circumstances of Ganja and Hess three years later as promising much more creative and commercial leeway.

“Oh man…everybody’s some kind of freak,” shrugs merry widow Ganja (the extraordinary Marlene Clark, who’d also been in Stop) when wealthy anthropologist Dr. Hess (Duane Jones) hints she’s now dealing with something bigger and darker than her own materialist ambition. She’s invaded his impressive manse in pursuit of the husband (Gunn) who arrived here earlier as Hess’ research assistant and left as a neurotic suicide. Albeit not before he’d stabbed Hess with an ancient “cursed dagger” that turns the good doc into an immortal, and an addict. Addicted to blood. BLOOD!!!

Lurid as that summary may seem, Ganja and Hess is anything but a standard boobs- and fangs-bearing vampire flick. Instead, it’s digressive, experimental, ambiguous, poetical, educated and fascinating…everything that the exploitation (let alone Blaxploitation) market would have found anathema in 1973. Imagine Ganja playing city-center grindhouses or rural drive-ins of the era: Patrons of all races, accustomed to more conventionally gory treatments of such themes, would have fallen asleep. Or thrown their popcorn boxes. Or their Mad Dog pints.

This one-of-a-kind movie, with its mix of supernatural suspense, black church-culture documentary (a prominent element tough to fit into a plot description), seemingly improvisational sequences, vividly erotic ones (including some startling full-frontal nudity) and flights of visual/sonic experimentation, is unlike anything anyone else was making in 1973. It has more in common with serious, adventuresome seventies African American indies like Sweet Sweetback’s Baadassss Song and Killer of Sheep than with the era’s concurrent blaxploitation norm. Such as:

No wonder Ganja was so ill-treated. Perceiving it as a dud, the film’s distributor drastically cut half an hour, changed other elements for the worse, and released the film as Blood Couple. Its initial home-format releases after that initial flop were no more successful, or representative of its real strengths. While erratic, Ganja and Hess remains a stunner in its sheer complexity and ambition. It is to the same year’s Scream Blacula Scream as Daughters of the Dust is to B*A*P*S.

Following that of Stop, Ganja’s fate must have been hugely discouraging to Gunn. In its wake, he basically abandoned screen acting, his sole later credits comprising a lead in Kathleen Collins’ little-seen African-American feature Losing Ground (1982) and a few years later, curiously, a couple guest shots on The Cosby Show. (He also directed the mysterious Personal Problems, a “black soap opera” shot in 1980 but apparently never broadcast.) Instead, he re-focused on his stage career, which had a powerful champion in New York Shakespeare Festival founder Joe Papp. When Gunn died at age fifty-nine in 1989, it was on the eve of his latest Public Theater premiere directed by Papp, “The Forbidden City.”

Despite its limited, compromised release (additional re-release titles purportedly included Black Evil, Vampires of Harlem and Blackout: Moment of Terror) Ganja and Hess remains his best-known work by far. From its curious opening plot-spoiler (or perhaps plot-clarifying) onscreen text to its closing children’s church choir, it’s an unclassifiable work still bound to frustrate those anticipating standard horror or action content.

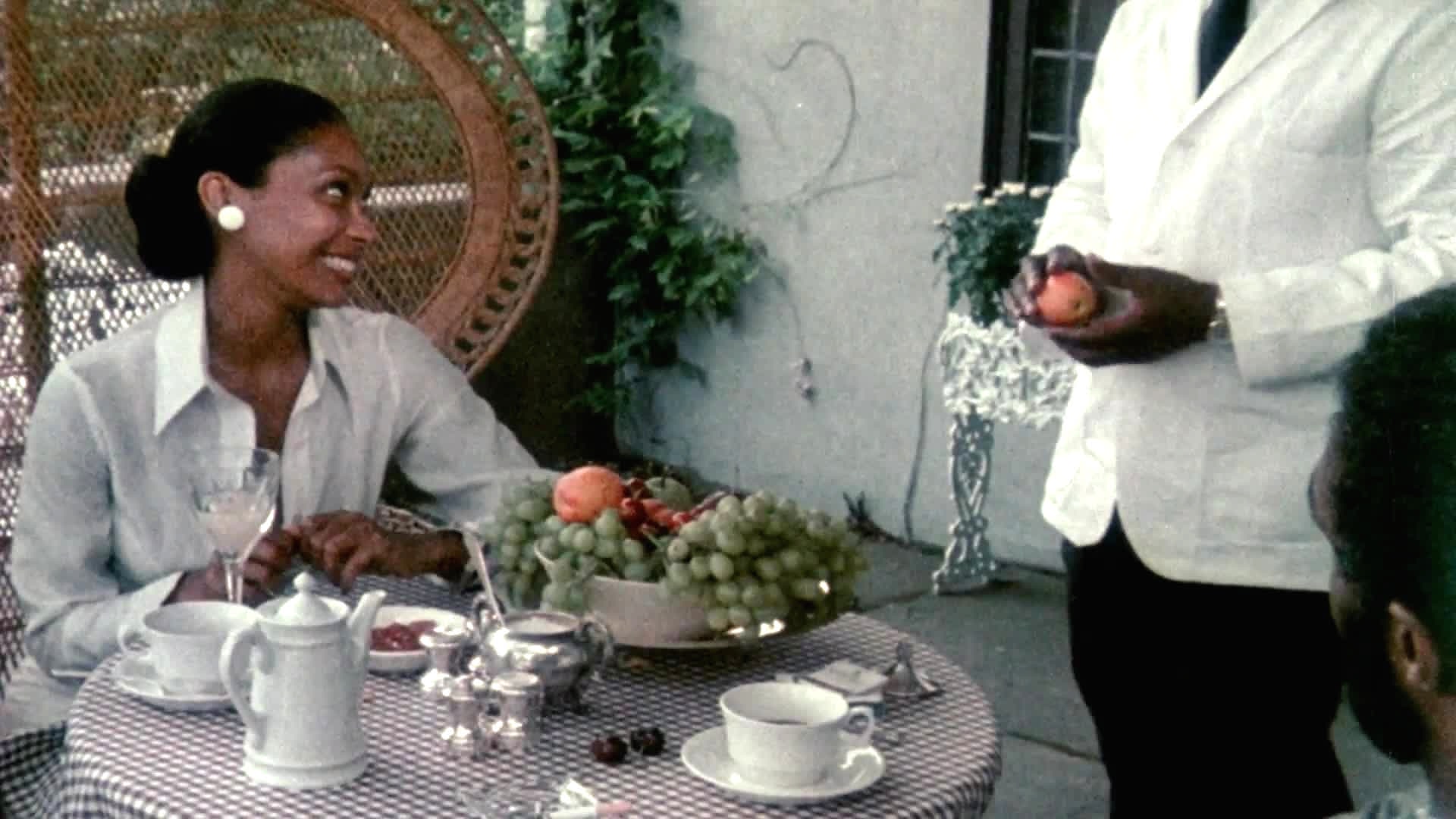

The narrative structure and thematic sprawl may seem haphazard, or exhilaratingly reckless, or both. But Ganja in its original, intended form hangs together as a unique vision, thanks in part to its charismatic lead actors. Dynamic Clark clearly relishes playing a contrary, complicated, smart, spoilt and not entirely sympathetic figure, so different from the sillier roles she got in movies like Slaughter, Black Mamba or Night of the Cobra Woman, let alone her myriad guest appearances in TV shows like Bonanza and Mod Squad. Here she is, making a living, in 1975’s voodoo melodrama Lord Shango:

Playing “Professor Hess” is sexy, thoughtful, 6’2” Jones, at one point seen rather startlingly full-frontal nude…running in slow-motion, yet. This was his only lead role outside legendary no-budget zombie classic Night of the Living Dead, where he famously played the coolest head in a houseful of panicked citizens besieged by flesh-eating freaks.

Famous not just because Dead became one of the most successful horror movies of all time (though a copyright-registering error meant its makers saw almost none of its extraordinary profits), but because Jones virtually had the field to himself as an African-American lead in an otherwise mainstream aka white exploitation feature. His resourceful bravery amidst a character cast of otherwise fairly dim bulbs was a very deliberate choice in a racially heated era by director George Romero and co-scenarist John Russo.

In Ganja and Hess, Clark and Jones play an upwardly mobile vampire couple more reminiscent of Bowie and Deneuve in The Hunger a decade later than any concurrent seventies “blood couple.” They’re educated, they’re erudite, they’re gorgeous and well-dressed. The wild card in their path from privilege to perverse bloodsucking is played by Bill Gunn himself, as Ganja’s errant husband and Hess’ new research assistant. Pouring a lifetime of bottled-up bonkers thespian energy into one custom-written screen part, Gunn is on fire in his Ganja and Hess scenes. He’s witty, he’s wild, he’s suicidal for no obvious reason whatsoever.