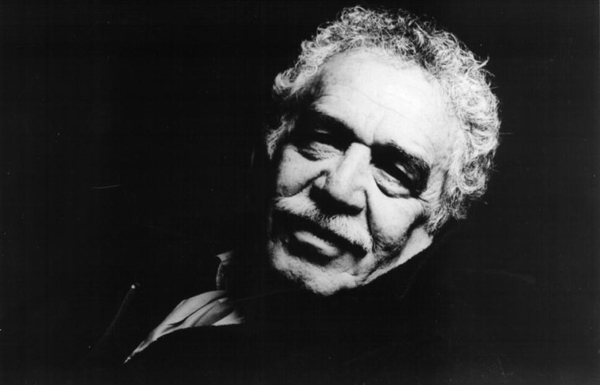

“Gabriel García Márquez, the Colombian novelist whose One Hundred Years of Solitude established him as a giant of 20th-century literature, died on Thursday at his home in Mexico City,” reports Jonathan Kandell for the New York Times. “Mr. García Márquez, who received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982, wrote fiction rooted in a mythical Latin American landscape of his own creation, but his appeal was universal. His books were translated into dozens of languages. He was among a select roster of canonical writers—Dickens, Tolstoy and Hemingway among them—who were embraced both by critics and by a mass audience.”

For the Los Angeles Times, Chris Kraul and Anne-Marie O’Connor report that the news of García Márquez’s death at the age of 87 has been met “with an outpouring of grief and reverence for the writer known to his admirers simply as ‘Gabo’… García Márquez did not invent magic realism—the blending of fantasy and outrageous facts ‘told with a straight face,’ as he once put it. The style was pioneered by Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier, Mexico’s Juan Rulfo and Argentina’s Jorge Luis Borges. But Garcia Marquez certainly burnished the technique with the publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude, the tale of four generations of the Buendia family set in a backwater banana depot he christened Macondo but which was based on his birthplace Aracataca, near Colombia’s Caribbean coast.”

“Do you think any books can be translated into films successfully?” the Paris Review once asked. García Márquez: “I can’t think of any one film that improved on a good novel, but I can think of many good films that came from very bad novels.” Next question: “Have you ever thought of making films yourself?” García Márquez:

There was a time when I wanted to be a film director. I studied directing in Rome. I felt that cinema was a medium which had no limitations and in which everything was possible. I came to Mexico because I wanted to work in film, not as a director but as a screenplay writer. But there’s a big limitation in cinema in that it’s an industrial art, a whole industry. It’s very difficult to express in cinema what you really want to say. I still think of it, but it now seems like a luxury which I would like to do with friends but without any hope of really expressing myself. So I’ve moved farther and farther away from the cinema. My relation with it is like that of a couple who can’t live separated, but who can’t live together either.

García Márquez does have more IMDb credits than your run-of-the-mill Nobel Prize-winner, though. He directed a short, wrote or co-wrote several screenplays and, of course, has had several films based on his stories. The best known adaptation is probably Mike Newell’s Love in the Time of Cholera (2007) with its screenplay by Ronald Harwood.

“Small wonder that One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez’s best novel, has never been filmed,” wrote Roger Ebert. “Watching Love in the Time of Cholera, based on another of his great works, made me wonder if he is even translatable into cinema. Gabo’s work may really live only there on the page, with his lighthearted badinage between the erotic and the absurd, the tragic and the magical. If you extract the story without the language, you are left with dust and bones but no beating heart.”

Updates, 4/18: Paul Berman for the New Republic:

There is a lordly grandeur in Gabriel García Márquez’s writing, and the grandeur animates every one of his books because, from beginning to end, he was gripped by an impossibly grand conundrum, which is the contradiction between lofty literature and lowly life. His characters uphold a glorious or even mythological concept of themselves, as if they were heroes of epic poems; and yet life insists on realities that are neither heroic nor mythological, until the characters end up battered and wounded. And, even so, they go on subscribing to their own version of events. They are noble losers, and the gap between nobility and losing is infinitely pitiable. In the greatest of his novels, The Autumn of the Patriarch (greatest in his own eyes, and in mine), you could almost weep even for the monstrous dictator, whose estimation of himself bears no relation to reality. In the greatest of his non-fiction books, News of a Kidnapping, about the Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar and his kidnapping ring and its victims, you experience fear more than pity; and yet the gangsters and thugs likewise turn out to be immured in their own superstitions and crazy notion of themselves.

More from Nick Caistor (Guardian), Edwidge Danticat (New Yorker), Steve Erickson (American Prospect), Pico Iyer (Time), Michiko Kakutani (NYT), Kathryn Schulz (Vulture) and Edmund White (Guardian).

In the Los Angeles Times, Oliver Gettell takes “a look at some movies made from his books and how they fared.”

Meantime, the New Yorker‘s posted an excerpt from that great 1975 novel The Autumn of the Patriarch and the New Republic is running an excerpt from Michael Jacobs‘s book, The Robber of Memories: A River Journey Through Colombia: “He was a man of the people, a lover of low life, a person with the grassroots appeal of a football star.”

Update, 4/25: García Márquez has left behind an unpublished manuscript tentatively titled We’ll See Each Other in August (En agosto nos vemos), reports Jason Diamond at Flavorwire. The estate has not yet decided whether to allow it to be published.

Updates, 4/28: “García Márquez’s career as a writer was always closely intertwined with film criticism and screenwriting, beginning with his work as a film critic in the early 1950s in Barranquilla and then Bogotá, where he churned out reviews of commercial exhibitions (mostly American, French, and Italian film) alongside cineclub screenings.” At Mediático, Rielle Navitski looks back on the writers life in the cinema.

Also via Catherine Grant, there’s more from poet Emma Scully Jones at Indiewire‘s /bent.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.