The sharp elbows and lengthy queues that characterize so many international film festivals are nowhere to be found in Fribourg. Situated in the Swiss plateau, the pace is almost as still as the river Sarine than runs through it. Sessions are spread out with plenty of time to take in the region’s impressive views before returning to darkened rooms to cast one’s eyes over the antithetical focus of the program: rebellion, protest, determination. Recognizing “individuals who struggle” as a contemporary cinematic concern, the landscape of the festival is as rich as Switzerland’s cultural and linguistic heritage. Hailing from forty six countries the 28th Fribourg International Film Festival showcases one hundred twenty six films that are anything but sleepy.

With this year’s special focus on Iranian cinema, curated by its creators, FIFF has undertaken a project so impressive that it can’t be confined to just eight days and one small city. Some of the films will also be screened in the nearby city of Lausanne and long after FIFF closes the project will see a new lease of life at the Edinburgh International Film Festival where Artistic Director Chris Fujiwara and his team will continue the rediscovery. Finally, the TIFF Cinémathèque in Toronto will take the reins, ensuring this important cross section of pre- and post-revolution Iranian cinema is more widely seen. International exhibition of so many of these films has been restricted for a number of political reasons over the years. Filmmakers who have taken part in the project include Asghar Farhadi, whose Academy Award winning film A Separation (2011) screens in the program, as well as Bahman Ghobadi, Mohsen Makhmalbaf and Jafar Panahi, to name but a few.

Still, even after the festival’s significant efforts to shine a light on these rare gems, the scope for large audience reach is limited due to language barriers. Though of the films in this section are accompanied by French subtitles, with a spattering of secondary subtitling in German or English, more than half the films they hoped to screen were altogether without, leaving the program wanting. A little too challenging for my elementary French and entirely too difficult for my non-existent Farsi, I’ve navigated my way through this strand with a preference for comprehension. Films such as Dariush Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969) and Forough Farrokhzad’s The House is Black (1963) remain a mystery to me, for now.

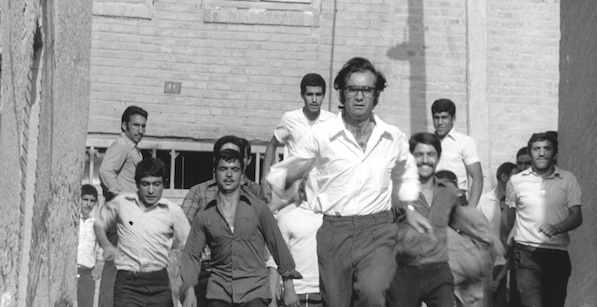

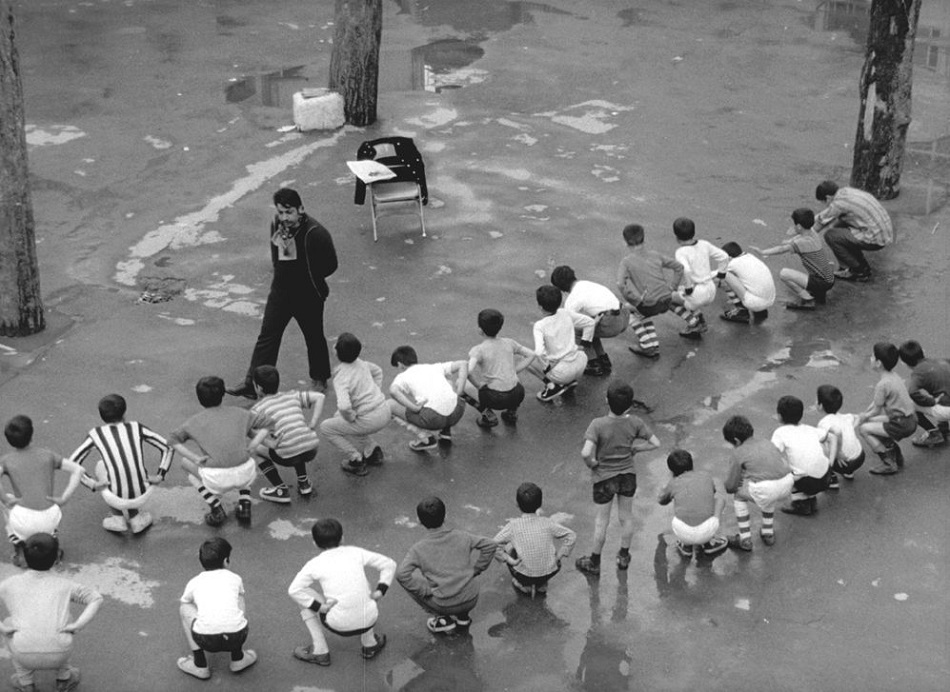

Bahram Beizai’s Downpour (1972), however, was one big-screen treat I was eager and able to attend. The film follows Hekmati (Parviz Fanziadeh), a young bachelor starting a new post as teacher at an elementary school in Teheran. Already mindful of the stigma that surrounds his bachelor status, Hekmati does his best to tread carefully around neighbors and colleagues—especially the women. He soon finds himself way out of his depth though and unwittingly develops a crush on the older sister of one of his students. Always unsure of himself and not wanting to overstep delicate social boundaries, Hekmati blusters his way through an almost romance, completely charming the audience in the process. Even if things didn’t work out in his favor on-screen, his beaming face will certainly linger in the mind’s eye of the viewer. Stylistically the film is reminiscent of the cinema of Satyajit Ray; our anti-hero is often shot from low angles and the camera is never too shy to sustain a close-up long enough for the audience to elicit and express their response.

Another rare collection of films, curated by yet more highly esteemed filmmakers, this time Belgian greats Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, nicely bridged the gap between retrospective and contemporary output. The films come from the Dardennes’ own production studio, Dérives, set up in 1975 in their hometown Liège. Though most of the films carry their stamp of approval as producers or editors, the first in the series was one they’d written, directed and filmed themselves.

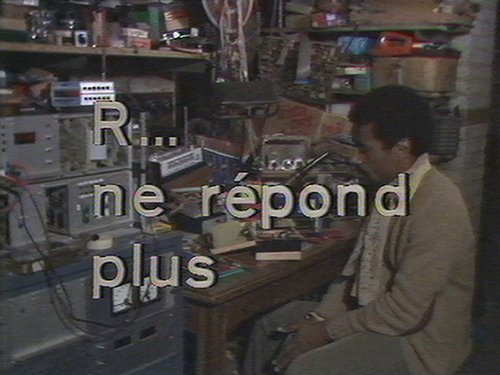

Itself a celluloid palimpsest, R… ne répond plus (R… No Longer Answers, 1981) surveys a number of pirate radio broadcasters from the region, seeking to expose their voice as a well-meaning yet obfuscating tool for disseminating “reality”—whatever that might mean. One broadcaster even views itself as “a radio station that is free because instead of opinions, it broadcasts facts.” Though the Dardennes happily admit this was a “naïve position,” their documentary is never interested in making fools of its subjects. Instead, what they are preoccupied by is the task of examining the disembodied voice of resistance. Evidently, at this early stage in their career the Dardennes were already intuitive, intelligent filmmakers; their use of repetition creates an astute feedback loop in the narrative that works superbly to destabilize audience expectation.

The only truth or reality one can glean from such a picture then is that so much discussion eventually becomes noise until all ideals must be abandoned. All that’s left in the end is the enabling apparatus. As the microphone and headset sit atop an empty studio desk, the Dardennes keep filming. Lost in the image of absent voices, we become almost too aware of the artificiality of what we’ve just seen. An intricate jigsaw puzzle of a film, R… ne répond plus certainly sticks in the mind. But perhaps the most puzzling item of all is why the Dardennes didn’t continue with documentary filmmaking; the field certainly would have been all the richer for it.

The employ of a close authorial presence, which the Dardennes’ own fiction films are so well characterized by, is also notably present in the films of their protégés. Intimate camera work that carefully observes its subject is as evident in Jasna Krajinovic’s La Chambre de Damien (2008) as it is in the Dardenne’s own 2002 film Le Fils. Krajinovic follows the titular young man as he approaches the end of his jail sentence for murder. Always just by his side or hovering close behind him there is an undeniable presence of director in each shot, and yet Krajinovic skillfully gives little away. There is something slightly sinister and almost confronting though about our knowledge that we are not alone when we observe Damien—even during those most difficult moments when we might actively want Krajinovic to tell us, rather than show us, how to feel.

Stepping now into the current cinematic climate, the festival offers a rather sobering collection of films under the banner of Decryption: Struggle for the Crisis. Including Alex can Warmerdam’s Borgman (2013) and John Maloof and Charlie Siskel’s Finding Vivian Maier (2013) this section is concerned with the notion that the political is personal. Sebastien Pilote, who the programmers at FIFF discovered last year in Cannes, has only made two feature films to date and both made the program: Le Vendeur (2011) and Le Démantèlement (2013). Pilote is a remarkable talent, and his carefully controlled, slow paced debut brings with it the promise of a bright future. Though the crisis itself is not the primary focus of Le Vendeur, the way it feeds into his characters’ isolation and loneliness creates a truly moving portrait out of mere moments of listlessness. Watching it filled me with so much sadness that I wanted to run straight into the arms of a loved one when the credits rolled, but, wiping my tear-stained cheeks after the house lights came up, there were only silent streets and a distant view of snowy mountains there to greet me.

Even the most outrageous programming felt cushioned by the city’s unofficial curfew: a string of titles that fit loosely into the “midnight movies” category kick off just after nine or ten of an evening. Though even I can admit watching Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing (2012) at midnight would be tough, there are other titles that are truly made for nightwalkers. I’m talking now of Kim Ki-Duk’s Moebius (2013), a complete gremlin of a movie that should come with a short list of rules like the proverbial mogwai. Unfortunately, I’m loath to elaborate too much; the less said about what happens in this incredible picture the better. Basically everything is shocking and therefore saying anything at all could be considered spoiler territory. I will however admit that just minutes into the film my jaw literally dropped—let’s just say the Lacanians will have a field day!

From charming to unnerving cinema, through true sadness and into genuine shock, I can honestly say that while the city is sleepy, I never needed an elbow to the ribcage to jolt me to attention; the films managed that with aplomb.