There are cult horror filmmakers aplenty, and then there’s Frank Henenlotter—one who never went mainstream (unlike say Wes Craven, Tobe Hooper or Sam Raimi), never made a bad movie (even Basketcase 3 isn’t THAT bad)—and re-emerged from a nearly two-decade absence with chops entirely intact.

His is a small body of work (so far), but its outrages and delights are completely distinctive. He’s never had a popular hit, and—apart from the getting-funding-for-the-next-one downside—one imagines he prefers it that way. Raised on grindhouse cinema as a native New Yorker, he’s an authentic latterday grindhouse maker, not a creator of expensive homages a la Tarantino. “I never felt that I made ‘horror films,'” he’s said. “I always felt that I made exploitation films.” That’s not a distinction you’d hear many directors voice out loud.

For sure, his movies fit the old-school “exploitation” label in that they’re invariably sensationalistic, albeit in a good-humored, often hilarious way—mixing gore, sex and grotesque combinations of both to outré results. Invariably his protagonists are nerdy guys with some sort of bizarre addiction that nose-leads them to mayhem. This can take the form of supporting a freakish twin brother’s needs, getting high on a murderous host monster’s euphoric brain injections, reviving a dead fiancé by most unnatural means, or the full-on sex/horror extravaganza that is Bad Biology. (We’ll detail that one later.) His is wiseass, misfit genre cinema par excellance. And unlike most fanboys turned low-budget filmmakers, he has original ideas—and knows just how to execute them.

Born in 1950, Henenlotter was ideally positioned to enjoy the sleazy peak of Manhattan’s grindhouse cinema (and general) culture in the sixties, seventies and eighties, before Giuliani and Disney-fication cleaned up the joint. He began shooting amateur films as a teenager; later, his short Slash of the Knife played an actual 42nd St. grindhouse as warmup to a midnight showing of John Waters‘ notorious 1972 Pink Flamingos. But it wasn’t until he made his first microbudget feature that Henenlotter became a midnight sensation himself.

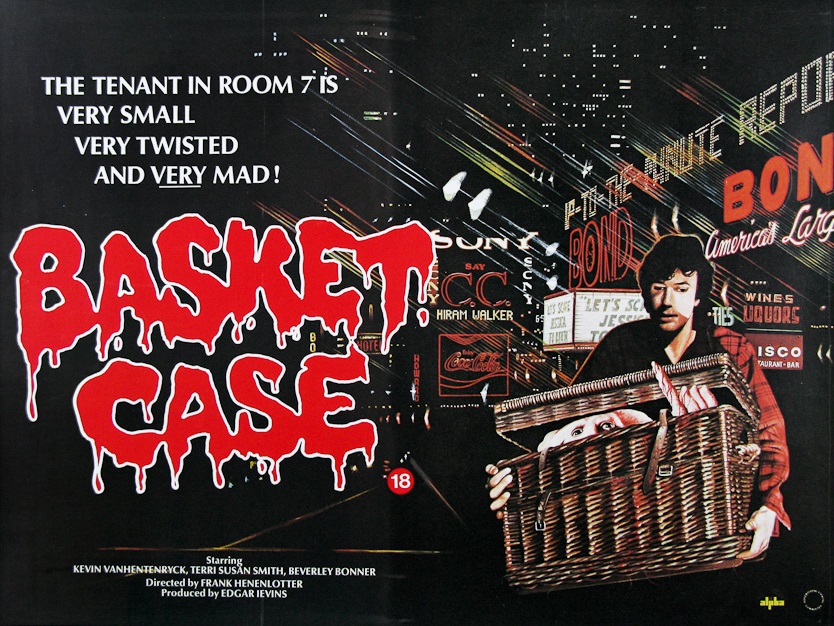

1982’s Basketcase is the tender tale of a boy and his luggage—a large wicker basket containing the socially unacceptable, biologically improbable body of the homicidal Siamese-twin brother he was surgically separated from years earlier. “Belial” is a legless lump of animate Play-Doh with teeth, and then some. It became a major hit on the then-still-lively midnight movie circuit. Still, it was four years before Henenlotter released another film: The similarly grotesque yet oddly poignant Brain Damage, in the shy guy hero played by Rick Hearst (later a staple on afternoon TV soap operas) finds himself enslaved by his neighbors’ runaway “pet,” a malevolent talking snake-like thing that gives him hallucinogenic highs in return for being led to human victims it treats with considerably less courtesy.

Brain Damage was a gem, its modest success leading to Henenlotter’s busiest year onscreen: In 1990 he released two features. Basket Case 2 was more of the same, amusingly so if edging toward deliberate camp. But Frankenhooker was something else entirely—so vigorously tasteless it had trouble getting released in some areas. After his fiancee (Patty Mullen, who mysteriously never made another movie after her stellar turn here) expires in a tragic lawnmower accident, medical student Jeffrey (James Lorinz) seeks to revive her by using the body parts of Times Square hookers he kills by introducing them to a literally explosive crack-like drug. When the new “Elizabeth” is fully animate, however, she isn’t the sweet girl-next-door of yore but a hardened streetwalker whose trademark screetch “Wanna date?” invariably proceeds the death of a john or three. Frankenhooker is frankly hilarious. Its original VHS box had an “interactive” cover which, when a lamp post image was pressed, piped a little electronic voicebox saying…well, you can guess.

Two years later, Basket Case 3: The Progeny drove the series over a cliff of jokey self-consciousness. It was not a success even in cult terms, and Henenlotter turned his attention to other pursuits—most notably curating a series of speciality retro exploitation re-releases for home video company Something Weird entitled “Frank Henenlotter’s Sexy Shockers.” It rescued dozens of ultra-rare grindhouse cheapies from complete obscurity, including such mind-boggling recommendables as The Curious Dr. Humpp and Ray Dennis Steckler‘s Bergmanesque sexploitation Sinthia the Devil’s Doll, not to mention hard-to-resist titles like Three on a Waterbed.

Evidently forgotten by financiers if not by fans, Henenlotter saw various projects fall through the cracks for the next sixteen years. But at long last rapper, online film critic/historian and sometime boxing commentator R.A. the Rugged Man sought him out, ponying up the cash to produce a feature co-written with the then long-inactive filmmaker. In terms of outrageousness, 2008’s Bad Biology puts all prior Henenlotter features—even Frankenhooker—in the shade. Yet it’s also funny as hell, in addition to being oddly sweet, particularly in contrast to such roughly comparable ilk as contemporary Japanese or Troma-style camp gore-horror.

Its two hapless protagonists—not destined to find one another until the cataclysmic final scene—are both the victims of, er, genital abnormalities. Music-video director Jennifer’s (actual musician Charlee Danielson) anatomical peculiarities drive her to serial one-night stands whose lucky male benefactors seldom survive the encounter. On the other hand, Brooklyn wigger Batz (a very funny Anthony Sneed) has been staying chaste for fear of the mayhem his mind-of-its-own member might wreak. These attractive “mutants” constitute a dual menace to society that resolves itself in the most alarmingly ridiculous fashion imaginable.

After that memorable return, Henenlotter co-diredted by Jimmy Maslon an exhaustive yet delightful documentary tribute to a favored role model. 2010’s Herschell Gordon Lewis: The Godfather of Gore reviewed the life and times of gore-horror’s original pioneer, who revolutionized the depiction of screen violence via cheerfully amateur, vigorously gross drive-in/grindhouse entertainments from 1963’s Blood Feast onward. Like Henenlotter, Lewis (now in his mid-eighties) returned after many long years of screen inactivity to make new movies—a belated Blood Feast sequel, reality-TV parody The Uh-Oh Show, and a purportedly imminent zombie flick.

In his frantic initial decade of exploitation filmmaking, H.G. Lewis made thirty-plus features. In over three decades, Frank Henenlotter has completed six—surely a testament to changed marketplace realities as well as a higher level of professional perfectionism. Still, one hopes the Basket Case auteur gets a whole lot closer to his elder’s numeric output before he’s done.