To paraphrase Sigmund Freud’s reputed remark about cigars, sometimes a movie is just a movie. There are times when all we want is entertainment and escape, with a dash of excitement and emotion. However, at Frameline 37, running a few more days in San Francisco and Berkeley, practically every show is a community event. Each program is truly a shared experience in which the presence and energy of the other moviegoers is as important as the skill and sensibility of the ostensible attraction.

One might expect that the hunger and urgency of seeing images of one’s self reflected on a big screen has abated in an age when hundreds of queer flicks are made worldwide every year and gay and lesbian characters live in plain sight on television. (Bisexual and transgender characters remain a rarity, no question.) You wouldn’t know it at the San Francisco International LGBT Film Festival, where the powerful dynamics of identity and representation remain crucial drivers.

Consequently, although advance screeners are available and essential for the press as they are at most film festivals, the SFILGBTFF needs to be experienced in a house full of paying customers. I caught three jammed documentaries, all of interest primarily to gay men and all at the fest’s flagship venue, the 1,400-seat Castro Theatre. Each screening was memorable in its own way.

I arrived at I Am Divine Sunday afternoon just as the lights went down, so I couldn’t see if the audience was dotted, peppered or packed with drag queens. (I tend to doubt there are fourteen hundred in the Bay Area, but demographics isn’t my field.) Nonetheless, the vibe in the house during Jeffrey Schwarz’s torridly paced and blissfully irreverent biography of the late Harris Glenn Milstead, the oversized actor and singer better known as Divine, was instantly recognizable. Along with torrents of laughter, a steady current of pride and appreciation flowed toward the screen for an individual whose flamboyance, fearlessness and dignity (out of character) had cleared a previously unimaginable lane for all gay men—from gaudy drag queens to butch corporate execs—to come out and be themselves.

From my straight-guy perspective, the one thing that was missing in the room, and from the film, was an acknowledgement that Divine’s influence extended beyond queer guys. He irrevocably changed the culture and the country, through cult hits such as Female Trouble and indirectly through the actions of those who came afterward and cited his influence. It is not hyperbole to say that every American lives in a freer, more colorful and more entertaining world thanks to Divine, even if he or she has never heard his name.

Schwarz (Vito, Spine Tingler! The William Castle Story) was on hand to invite onstage a handful of locals with a connection to Divine, including Scrumbly of the Cockettes, and to give a shout-out to David Weissman and Bill Weber’s essential 2002 doc about that gender-bending troupe of psychedelic theater artists. The filmmaker also explained that John Waters, who has an apartment in San Francisco and spends a chunk of the year here, missed the SF premiere because he was hosting his annual poppers party in Provincetown. (Joke or not, it was over my head….) Any readers unaware of the connection, and that the friend and director with the pencil mustache launched Divine’s improbable career in Baltimore, have some catching up to do.

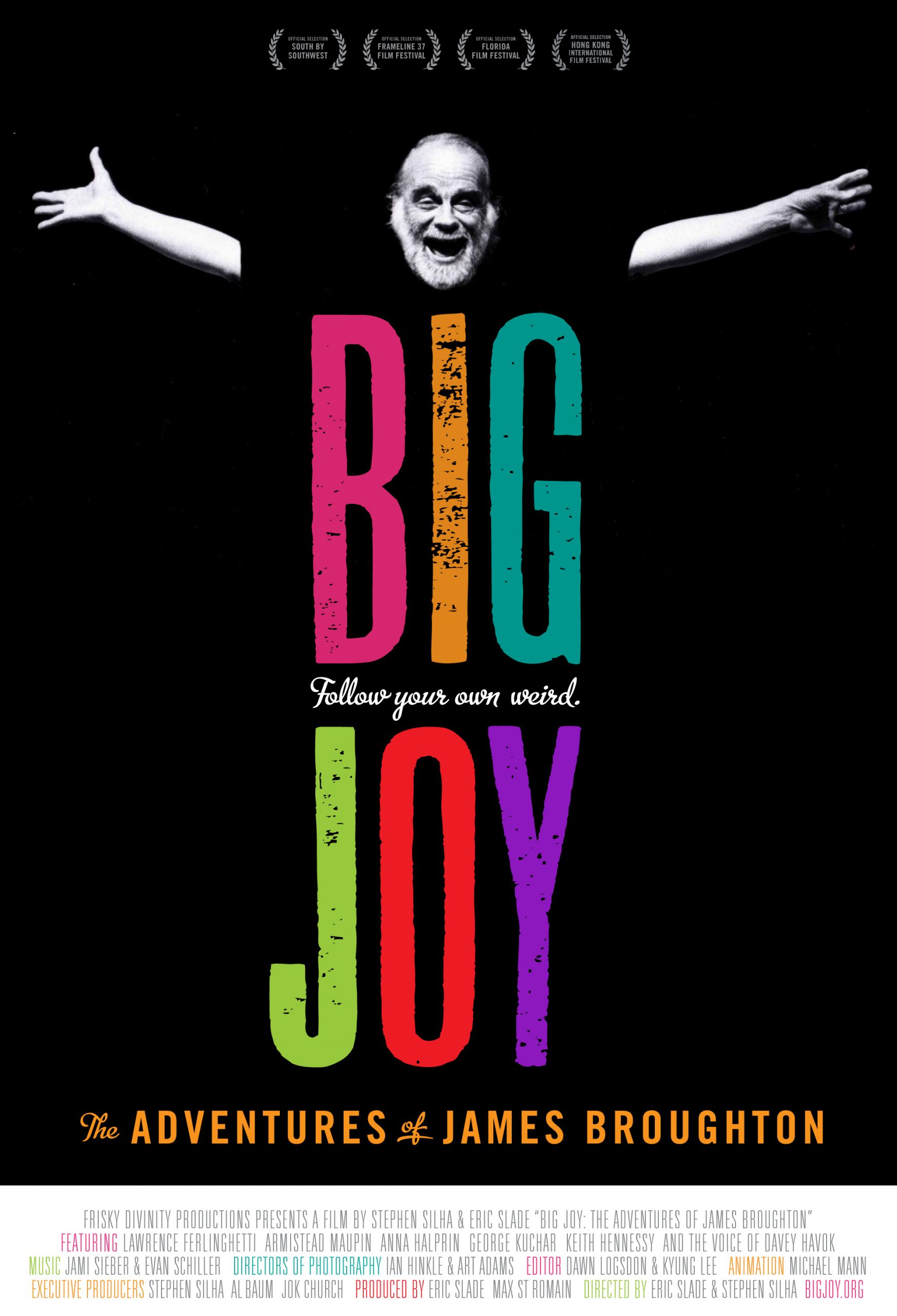

A slightly older and grayer crowd came out the previous day for the matinee of Steven Silha, Eric Slade and Dawn Logsdon’s exuberantly offbeat Big Joy: The Adventures of James Broughton. An important 20th Century poet and experimental filmmaker and a benighted free spirit (once he resolved or transcended his depression), Broughton was ahead of his time in navigating the strictures against homosexuality and the prejudices against bisexuality,

My colleague Steven Jenkins wrote a splendid review of Big Joy elsewhere on this site, so I’ll simply note that the crowd embraced the late Broughton as a cheerful, truth-telling sage as much as a gifted, original artist. The film was preceded by a hilarious blessing from a Sister of Perpetual Indulgence, the longstanding activist/charitable “sect,” and a veritable gaggle of Bay Area luminaries joined the filmmakers onstage after the closing credits, including the beloved dancer and choreographer Anna Halprin, the writer Armistead Maupin and a gold-garbed Cockette.

Every patron entering the Castro on Monday night for Malcolm Ingram’s Continental was offered a goodie bag from the festival’s longest-tenured sponsor, a gay gym/sauna/bathhouse in Berkeley. I was expecting a stash of lubricant and condoms, not the small blue cloth emblazoned with the sponsor’s logo that Frameline executive director K.C. Price referred to without embarrassment as a “cum rag.” (You hear and see things at the San Francisco International LGBT Film Festival that one no longer encounters in public places, and perhaps not since the introduction of porn on VHS put the seedy theaters on Market Street out of business.)

The crowd was primed for a lewd, lascivious and vicariously nostalgic excursion to the late sixties-early seventies heyday of the Continental Baths. This state of anticipation was cultivated, in part, by a program note (penned by the aforementioned Mr. Jenkins, coincidentally) that mentioned the orgy room and skinny-dipping in the pool, among the Manhattan hot spot’s other features.

To the disappointment of some, Continental turned out to be much more of a character piece and social study than a down-and-dirty sex romp. Steve Ostrow, the then-married opera singer and hyper-confident entrepreneur who saw an opportunity in pre-Stonewall New York for a well-maintained bathhouse that respected rather than exploited its gay clientele, serves as the main guide of this “you had to be there” saga.

The politicians and cops hadn’t caught up to the changing climate; gay sex flourished yet homosexuality was still illegal. Catering to enormous pent-up demand, the Continental was open 24/7 and accommodated 20,000 customers a week. Even persistent police raids couldn’t dampen the popularity of the vast bathhouse in the eye-catching Ansonia on the Upper West Side. A dance floor was installed and DJs played nonstop day and night—it was a heady time of sex, drugs and disco, baby.

Continental clearly places the baths on a gay timeline after the onset of the sexual revolution and long before AIDS altered sexual practices. What isn’t mentioned, however, is porno chic, the phenomenon sparked by the success of Deep Throat (1972) through which pornography traded its sordid associations for a cachet of hipness. Hetero sex came out of the shadows and into the mainstream.

The relaxation of sexual stigmas may help explain why Ostrow’s addition of live, cabaret-style entertainment on the weekends attracted a straight, in-the-know crowd to the Continental. By booking the likes of Bette Midler (who somewhat foolishly didn’t make herself available to be interviewed for the film), Labelle and Metropolitan Opera soprano Eleanor Stebel, Ostrow proudly expanded his business venture into a cultural destination.

Ostrow is an entertaining raconteur, but occasionally his commentary has the flatness of someone relating an anecdote rather than the immediacy of an experience being recreated anew. At the same time, Ingram (Small Town Gay Bar) grants him a tad too much freedom to present—and conceal—this pivotal chapter in his life as well as in queer history. The director does acknowledge Ostrow’s self-serving subjectivity with an amusingly edited sequence in which several interviewees good-naturedly contradict Ostrow’s recollections of those heady days.

Continental is a worthy and ultimately poignant addition to the canon of gay historical documentaries. (It’s also the broke Canadian director’s last such film for a while, Ingram confided during the Q&A.) Just set your expectations at a reasonable level, and look elsewhere for titillation.