In 1964, film critic/filmmaker André S. Labarthe and Janine Bazin (widow of André Bazin) started a television program in France called Cinéastes de notre temps (Filmmakers of our Time), later revamped for French-German cultural channel ARTE in 1988 as Cinéma, de notre temps. The series was known for long, in-depth interviews with some of the greatest filmmakers of all time, and was often made by great auteurs, too. Jacques Rivette would interview Jean Renoir in 1967, for instance, and then Claire Denis would interview Rivette in 1990.

For the 50th anniversary of the New York Film Festival, festival director Richard Peña along with Véronique Godard curated a showcase of this invaluable resource for one-of-a-kind, first-hand film history, which features many of the filmmakers whose work is available to view on Fandor. Throughout the festival and afterward, Keyframe will run a series of “Five Lessons from Ten Great Filmmakers.” We begin with Luis Buñuel, whose episode directed by Robert Valery screens on October 4 at 6:15 pm.

Lessons from Luis Buñuel

1. Don’t give too much away.

Before the screening of The Exerminating Angel in Cannes: Buñuel announced, “If the film you’re about to see seems enigmatic or incongruous, life is that way too.”

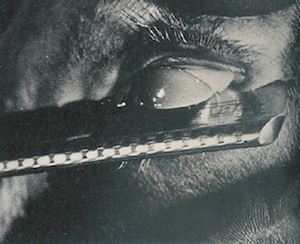

2. Begin with horror, or attract attention by shock.

Ricardo Urgoiti met Buñuel at the premiere of Un Chien Andalou. “At that time, the audience thought it was a terrifying film, especially the scene where the razor cuts through the eye,” he says. “Everyone was terrified, they didn’t understand the film. Nevertheless, it was a great success. At the end of the film, someone said, ‘What does all this mean? We don’t understand anything!’

Buñuel looking fierce as usual said, ‘It’s simple. It’s an appeal to murder and rape!’

He’s a brute, “un bruto” as we say in Spanish! But in fact, he isn’t a brute. He acts this way so we don’t see his true nature. He is actually very soft-hearted. He hides behind this fierce attitude.”

3. Contradictions are an artist’s prerogative (or the basis of his humor).

“Do you like Toledo?” asks the Robert Valery.

“Not really,” answers Spaniard Buñuel. “It’s dirty and the streets are smelly. We Americans like clean places.”

Later that evening, Buñuel says to Valery, “Evenings are very pleasant in Toledo. I will show you tonight.”

“You said you didn’t like this town!”

“This morning I didn’t, but I’m starting to love it… I can like something in the morning and hate it in the afternoon.”

4. Always come in under budget and on time

“What kind of films did you make as a producer?” asks Valery.

“Popular films,” is Buñuel’s answer. “I was an executive producer as I knew how cinema worked. My job was to reduce the number of days of production of a film. If they gave me 30 days, I had it done in 25 days. I pushed people to work faster. I was used to working on a tight budget. I attach little importance to appearance. I don’t try to dazzle the audience with compositions, costumes, sets or sceneries. I prefer human relationships… and atmospheres, even though they aren’t as important.”

5. Extinguish doubt, but be careful of ignoring it.

In explaining the character of Nazarin, Buñuel describes the insidious powers of doubt: “If you fell asleep with a cigarette in bed either it is put out in its own, or your house can catch fire. Doubt is like a cigarette, it either does nothing or destroys everything.”