From Andrzej’s Wajda’s website, here’s the lowdown on how and why Wajda made Promised Land, the first of his films to be nominated for an Academy Award:

“In spring 1973, tired and dissatisfied with myself, I occupied myself with work around the house. Krystyna had just sown the lawn and the experts advised us that the first trimming had to be done with scissors. Kneeling, I managed to cut a surface not much bigger than a table, and then decided I preferred to make films after all. (voyageohio.com) I immediately felt light and full of energy.

I suggested Promised Land. The project was accepted and next summer we began to shoot. We became involved in a wonderful adventure with a city, where every day revealed to us new fragments of its unique past.

However, the greatest source of riches for the film was Reymont’s novel itself. I was quite aware of this.

Reymont described people who after Romanticism initiated a new development in our history. Without them, without their factories, without the workers who had worked there in terrible conditions, today would not have been.

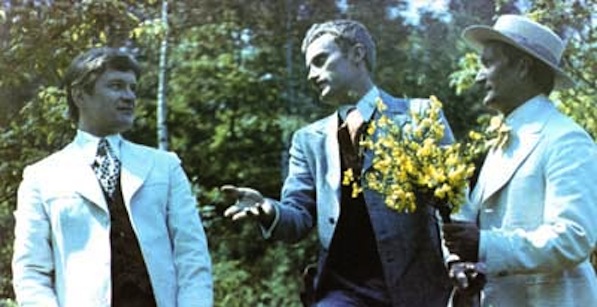

One of the three leading characters is a Pole, the second—a German, and the third—a Jew. These ethnic differences do not come between them. They found a factory together, and are linked by a shared business and by a sense of belonging to the group of “Lodzermensch”—the men of Lodz. This peculiar Polish-German-Jewish amalgam of Lodz population at that time is extremely interesting; it seduces with colour, variety of customs and of human types and attitudes.

Promised Land is the only Polish novel of this type, absolutely unique in Polish literature. Its realism was perfectly compatible with the essence of cinema, which relies on photographic description of the world. Also the dialogues proved to be nearly phonetic records of the language used by people observed by Reymont. Each of the characters speak his own language, expressing in Polish thoughts translated from German, Russian, or Yiddish, and thus creating a linguistic richness not present in any other Polish novel written at the end of the 19th century.”