[Editor’s note: As part of our Fifty Days, Fifty Lists project, the Film 101 series that continues today on Keyframe offers a short alternative course in cinema. By the time it’s completed in five parts over five weeks, you’ll have hit film’s floodlit high points and ventured down its dim back alleys. Notebook optional. For review, check out Film 101: Part One and for more, dip into Film 101: Parts Two, Three and Four.]

Desperate Teenage Lovedolls (1984)

While the 1970s was in many respects a very fertile, adventurous period for movies, it also planted the seed of the formulaic modern blockbuster. The staggering success of action thriller Jaws and sci-fi fantasy Star Wars sparked a turn toward imitative big-budget escapism that theoretically appealed to all, but primarily reflected a forever-young male mindset. The 1980s Reagan era furthered that with such hits as Top Gun and the Rambo movies, not to mention uber-macho stars like Schwarzenegger and Chuck Norris. It was inevitable, perhaps, that a new “underground” would emerge in reaction to all this bombast. Partly bred by the punk scene and art schools, U.S. independent filmmaking became far more prolific and popular than ever before, creating its own breakout directorial stars like Jim Jarmusch (with 1984’s Stranger than Paradise) and Steven Soderbergh (who almost singlehandedly turned the Sundance Film Festival from a cozy little affair to an annual industry feeding frenzy with 1989’s Sex, Lies, and Videotape. Some such talents would eventually “go Hollywood,” balancing personal and major-studio projects like Penelope Spheeris (Wayne’s World) or more recently David Gordon Green (Pineapple Express). But many remained stubbornly “indie,” among them, SoCal punk chronicler David Markey. His hilarious mockumentary Desperate Teenage Lovedolls ridicules the movie and music industries alike as it chronicles the melodramatic rise and fall of a fictive pre-riot-grrl rock band. Its cult following demanded a sequel, 1986’s even better Lovedolls Superstar.

Days of Being Wild (1990)

World cinema is oceanic, with some reliable currents and centers of breeding life. But you can never fully anticipate where the next tsunami or monsoon might hail from, let alone how large or long-lasting it might be. For a while after World War II, several European nations (including France, Sweden, Czechoslovakia and Germany) led the way in “New Wave” artistic innovation. A few decades later, cineastes discovered exciting signs of renewed celluloid life far to the East, as nations from South Korea to Malaysia began produced bold young talents. Long the commercial filmmaking center for Chinese-dialect audiences (and international fans of martial arts movies), Hong Kong attracted fresh critical admiration with the rise of a new generation in the 1980s. Many of its emerging voices brought high style and vigor to familiar action genres, like John Woo (1986’s crime drama A Better Tomorrow). Others’ idiosyncrasies were more unclassifiable. Wong Kar-wai announced himself as a true auteur with 1990’s Days of Being Wild, a restless mood piece of unrequited loves set thirty years earlier. Its gorgeous aesthetic (representing the director’s first of many collaborations with cinematographer Christopher Doyle), starry cast and impressionistic narrative would remain elements in nearly all his subsequent films, from gay breakup drama Happy Together (1997) to lavish costume epic The Grandmaster (2013).

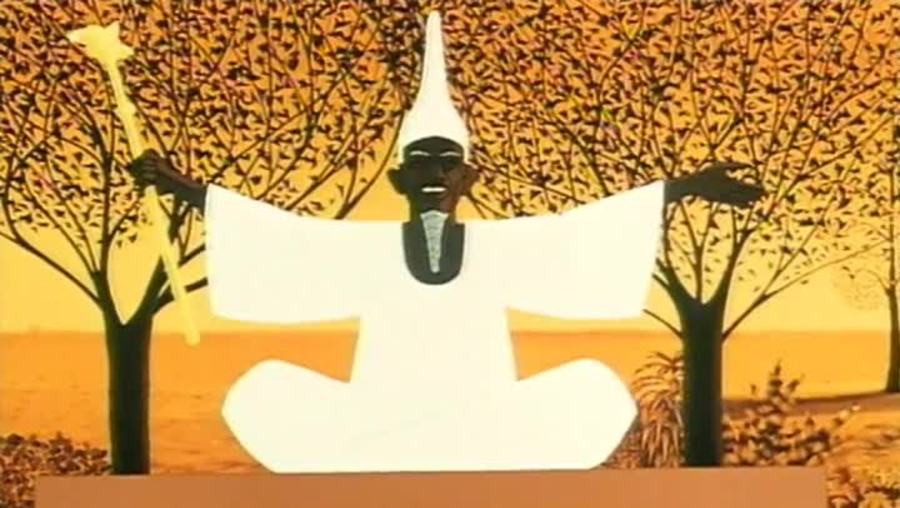

Kirikou and the Sorceress (1998)

Animation remained a staple of the medium through the decades, albeit mostly still limited to kid stuff despite occasional exceptions like Bruno Barretto’s scabrous Fantasia parody Allegro non troppo (1976) and the awards-laden output of Zagreb Film in Croatia. (Not to mention American Ralph Bakshi raunchy seventies features, kicked off by the X-rated hit Fritz the Cat.) Though many thought the Disney studio’s inspiration slumped after founder Walt’s 1966 death, his influence on cartoons remained almost oppressively strong. But that slowly began to change as emerging talents widened the form’s reach via innovative work for TV and the big screen. U.S. computer animation house Pixar (Toy Story) and Hayao Miyazaki’s traditionally hand-drawn features (Spirited Away) for Japan’s Studio Ghibli delight grownups as well as their offspring. Farther off the beaten track, there have been adventuresome efforts like Nina Paley’s virtually one-woman show Sita Sings the Blues (2008), a delicious spin on Indian mythology, or French animator Michel Ocelot’s multinational coproduction Kirikou and the Sorceress, drawn from West African folk tales. The latter spawned two sequels (and a stage musical), but its popularity wasn’t universal: Characters’ casual nudity, true to their tribal lifestyles, was deemed unfit for family consumption in some countries. Including, yes, our own.

The Mill and the Cross (2011)

As fragile, costly 35mm film gave way to digital video as a shooting format, so too technological advances have helped shape what actually gets depicted onscreen. CGI (computer-generated imagery) made just about anything possible, bypassing the previous physical limitations of stuntmen, production designers and old-school special effects. But many have lamented in recent years that Hollywood only applies this theoretical new freedom to a dismayingly juvenile, video-game-influenced lexicon of repetitious ideas: Superheroes, fantasy monsters, sci-fi dystopias, mass destruction, etc. Fortunately, filmmakers working with tiny fractions of typical “blockbuster” movie budgets have found more truly imaginative applications for those technologies. Expatriate Polish director Lech Majewski’s The Mill and the Cross uses cutting-edge techniques to look backward at a distant era’s most sophisticated art form. Blade Runner villain Rutger Hauer plays Flemish painter Bruegel the Elder, whose 1564 epic canvas “The Procession to Calvary” here “comes to life” via an ingenious mixture of live action and computerized images. This droll, one-of-a-kind feature probes that masterwork’s subtle political and religious symbolism while revealing the everyday cruelty (as well as the simple joys) of a period marked by stark class divisions, suffering and superstition.

We Are Mari Pepa (2013)

Those who claim there’s nothing to see at the movies anymore are, as ever, usually looking in all the wrong same-old places…like the multiplex. Exciting work continues to be made outside the mainstream marketplace, whether from improbable late-breaking cinematic hotspots like Romania or from the latest first-time director telling his or her stories with DIY enthusiasm and resourcefulness just about anywhere. At once a “typical” such debut and an exceptional one is Samuel Kishi’s Mexican We Are Mari Pepa, which followed a now-familiar path to the screen by expanding on a well-received prior short. Its protagonists are four middle-class Guadalajara boys whose rock band (the one they barely have the patience to practice their instruments for) provides just one amplification of myriad roiling sixteen-year-old emotions. While the autobiographical “coming of age” saga may risk cliche as a young director’s vehicle, its cliches can also feel as fresh as the inspiration brought to it. As long as movies this joyful and (eventually) soulful are being made, the oft-proclaimed news of cinema’s demise will remain premature.