Born in Mexico City in 1970, Fernando Eimbcke studied film direction at the Centro Universitario de Estudios Cinematográficos at UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico), where he first endeavored making short films, both fiction and non-fiction. He continued making shorts after his graduation, and began directing music videos. In 2004, he co-wrote and directed his feature debut, Duck Season, which premiered at Cannes in the Critics Week sidebar, was programmed at numerous film festivals worldwide and won no fewer than eleven Ariels back home in Mexico, including Best Film, Best Director and Best Screenplay. He followed up with Lake Tahoe in 2009, another award winner, and finally made an appearance at the San Francisco International Film Festival with his third feature, Club Sandwich (2013), at which time Eimbcke and I sat down to discuss his films. My thanks to Bill Proctor for arranging same.

Michael Guillén: First and foremost, congratulations on your Best Director win at San Sebastián, your Best Film win at Torino, and—just the other day—the Grand Jury Prize at the Nashville Film Festival.

When Duck Season (Temporada de patos, 2004) screened at the 2005 San Francisco International Film Festival, it served as a blast of fresh energy coming from Mexico. Up until then, the Tres Amigos (Guillermo del Toro, Alejandro González Iñárritu, Alfonso Cuarón) had received most of the media attention, but then here you came, along with Julián Hernández and others—a whole new generation of Mexican filmmakers. Can you situate yourself among your colleagues?

Fernando Eimbcke: Well, first of all, with regard to your question about where I place myself in association with Los Tres Amigos, Alfonso Cuarón was one of my biggest influences. When I was in film school, I saw Sólo con tu pareja (Love in the Time of Hysteria, 1991) and was surprised that it was such a strange comedy. I liked that film a lot and it was the first time I thought, ‘Oh, it’s possible to make a comedy in Mexican cinema.’ From that moment I followed the work of Alfonso and he surprised me with each film because each film he made was different.

Then Alejandro made Amores Perros (2000), which changed everything. It was a huge, intense film and was followed soon after by Carlos Reygadas‘ Japón (2002), while Guillermo del Toro was making films in Hollywood. For Mexico, it was a good moment for cinema because so much was happening. Around that time I met Emmanuel ‘Chivo’ Lubezki and he was the main reason I went to film school. I used to work as an assistant to a photographer who made a video for Thalía, a well-known Mexican singer, and Emmanuel Lubezki was one of the D.P.s. I asked him where he studied and he told me he went to the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

I wanted to be a photographer, but I didn’t have money to buy equipment. Lubezki helped me realize that I could use the equipment at the school to become a photographer. I was rejected the first time I applied because I wasn’t a true cinephile and had not seen a lot of films—I didn’t grow up in a family where we saw many films—so I spent the next year watching three or four films a day. That was when I truly fell in love with film. I applied again to the film school and this time they saw my love for cinema and I was accepted. I wanted to be a director of photography.

Guillén: I’m happy to hear you acknowledge Alfonso Cuarón and Emmanuel Lubezki as influences because—in most of the interviews I’ve read—you’ve talked more about being influenced by Ozu, Jim Jarmusch and Aki Kaurismäki, which is great of course; but, I’m glad to hear you acknowledge your Mexican influences. Did you have a chance to visit with Alfonso at the Morelia International Film Festival, where he and his film Gravity (2013) were being fêted?

Eimbcke: Yes. And I had also seen him at San Sebastián. He invited my wife and I to dinner. He’s a kind guy and a very good person. He actually distributed Duck Season.

Guillén: I didn’t know that.

Eimbcke: Oh, yes. We had taken Duck Season to a lot of film festivals and a lot of people in the United States said, ‘It’s an amazing film. It’s great. It’s wonderful.’ But no distributors took it. Alfonso saw the film in Cannes and fell in love with it. He told me he would help me strike a deal and he was able to do so with an independent distributor because he had just filmed Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004). He was so helpful.

Guillén: At Morelia last year, I was watching Alfonso interact with his fans and was much impressed with how good he was to them, how he didn’t place himself above them, taking time to sign hundreds of autographs and have his picture taken with them, and then I noticed that you, too, had that same manner with your fans. You’re always surrounded by young people who, I imagine, are inspired by you. I have to commend that.

Your three features—Duck Season, Lake Tahoe (2008), and now Club Sandwich (2013)—have common elements. Duck Season is a narrative about two boys without parental supervision, Lake Tahoe revolves around the loss of a father, and Club Sandwich is the coming-of-age of a mother. Can you speak to the importance of these parental frameworks in your films?

Eimbcke: I don’t really know. For me family is very important; but, family is not just your mother and your father. Family is also your friends. The characters in Duck Season are like a family. They become a family. I don’t know why in my films there is always the absence of a father. In Duck Season, Flama (Daniel Miranda) admits that his mother is separating from his father, whereas Moko (Diego Cataño) doesn’t know his father. That wasn’t necessarily in the script, but I knew that. Lake Tahoe, as you said, revolves around the absence of a father. And in Club Sandwich there’s a mother, but again no father. I don’t know why that theme keeps appearing.

Guillén: You had just come out of film school with Duck Season? Did that influence your decision to film in black and white?

Eimbcke: Okay. The real reason, the first reason, was because I wanted to make an ‘art’ film. When I started talking with my cinematographer Alexis Zabé, I asked him, ‘What if we made the film in black and white?’ and he said, ‘Yes, it could be!’ We decided this was best for the film. After that initial decision, we found many reasons why it was good that we were filming in black and white, in terms of framing (because we used a lot of geometrical compositions), and in terms of—this might sound a little strange—the black and white helped make Duck Season an urban film because the black and white felt like the street, like concrete. It also helped with the overall tone of the film: with the actors, the music, the camera, everything. Filming in black and white helped put all these things together into a certain tone. The rhythm of the film, the jokes, how they played, was all helped by filming in black and white.

Guillén: You mention the jokes and Duck Season‘s humor is one of its most attractive strengths. It’s a particular type of humor predicated upon awkward moments. You have some slapstick, as with the truth or dare sequence in Club Sandwich, which are hilarious and laugh-out-loud funny, but most of the time the humor arises from awkward moments. Can you talk about how you build your stories around these uncomfortable moments?

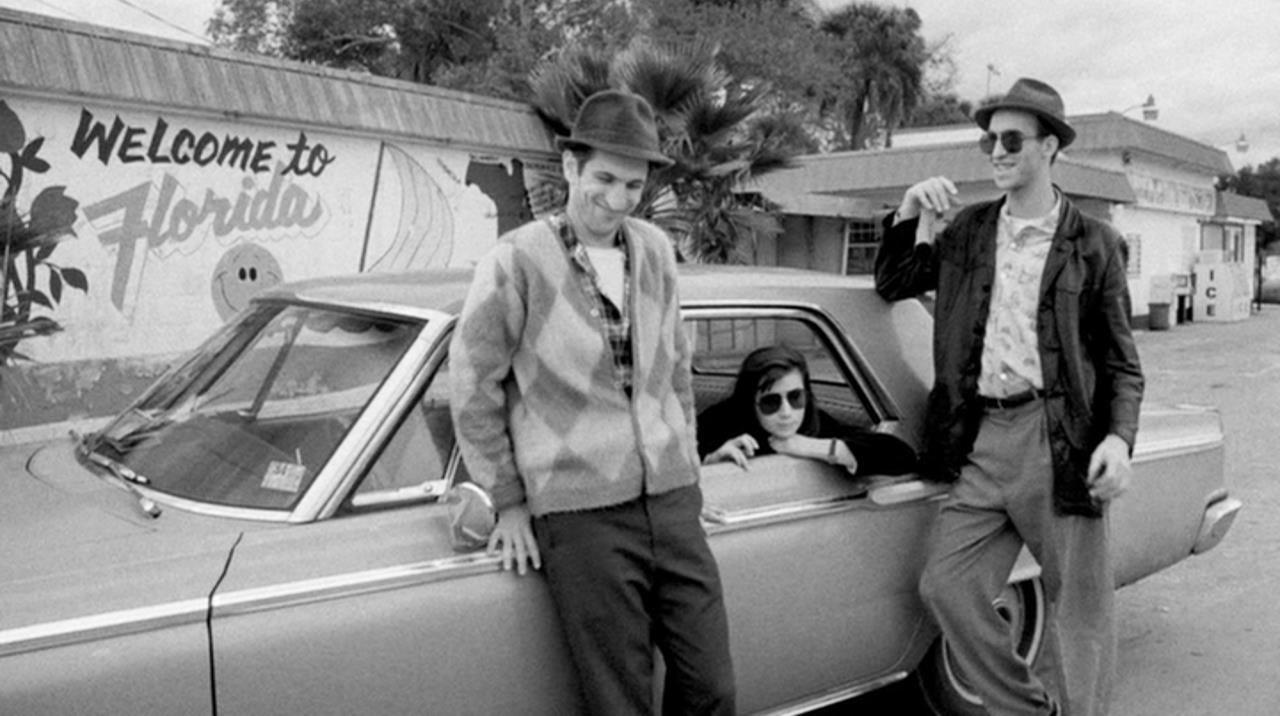

Eimbcke: I love those kinds of situations when people are not comfortable with each other. People do very funny things when they’re not comfortable. I like that kind of humor. I got some of that from Kaurismäki, and Jarmusch, too. I recognize their influence. One of my favorite films is Kaurismäki’s Leningrad Cowboys Go America (1989). When I showed it to my wife, she complained it was silly humor but that’s what I loved. Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise (1984) was an important film for me because—when it finished—I was like, ‘What was that about?!’ But I fell in love with the film’s rhythm, its humor. I like dry, deadpan humor that is not always hilarious humor.

Guillén: Do you anticipate that you will stick to comic narratives? Do you have any wish to make a serious film where people don’t laugh?

Eimbcke: I love comedy. Even when I’m watching a serious drama where terrible things are happening, I can still see the funny part because I believe there is always a funny part. I’ve been to memorials for the dead where a lot is happening in a family, but—if you see it from a slightly different perspective—a lot of what is happening is funny. They’re dealing with something painful, but then there are these special moments that are really funny. I like sifting out that kind of humor. I don’t want to make comedies that are hilarious chick flicks. I’m not interested in that. I’m interested in those awkward moments.

For example, in Lake Tahoe there is the death of the father, which is not funny, but there are moments where the character misunderstands the absurd things that are happening around him and those moments are funny.

Guillén: Your films plumb depths for their humor. What’s funny is what’s real in life.

Eimbcke: Thank you.

Guillén: Another element I admire in your films, moored on your impeccable casting, is their awareness of the existing class system in Mexico. Your characters come from a lower class edging into middle class. What comes across is an abiding respect for average, non-privileged people. A lot of Latino comedies are about upper class people doing stupid things, whereas yours are about real people who—as you said—find themselves in absurd situations.

Eimbcke: In 2010, I participated in an interesting film called Revolución with many other Mexican filmmakers: Carlos Reygadas, Amat Escalante, Gerardo Naranjo, Rodrigo García, Mariana Chenillo, among others. My story was set in a town in Mexico and—though I had never lived in that town and didn’t know the characters closely—I was respectful of my surroundings. I was there to see and learn. It doesn’t matter which social class I am making a film about, I will always be respectful. I have to be.

These characters from Duck Season to Club Sandwich are based on people who I know really well. The mother in Club Sandwich is someone I know very well. One of my biggest influences and one of my main teachers is Paula Markovitch, who made the amazing film El Premio (The Prize, 2011). We worked together on Duck Season and Lake Tahoe, though not on Club Sandwich. She’s been important to my career and to my work. In film school, the film writing classes were not so good because they only taught you how to make a short film. There wasn’t time to make a ninety-minute film and so they only taught you how to make a short film.

When I graduated from film school, I wanted to write my first script but I didn’t really know how to do it. I spent a lot of time writing and writing and writing, and going nowhere. I had good ideas but the scripts went nowhere. So I went to a workshop coordinated by Paula Markovitch, who I had known for some time. All of the other participants in the workshop ended up leaving because they had to work and earn money, leaving only me and Paula. That was lucky for me because I learned a lot from her.

I had the story for Duck Season; but, when we started the workshop, I was working on another story. Paula remembered that I had written a story about teenagers hanging out together on a Sunday afternoon. She remembered it being a very good story. ‘Let’s work it,’ she said and so we worked it. From her, I learned how to see characters. For example, as we discussed a little earlier, in Duck Season and Lake Tahoe there are no fathers. But originally I had written parents as characters into the story, but Paula said, ‘Your parents are terrible. They’re farcical. They’re not real. The way you’ve written your adolescent boys are great, but you don’t seem to like adults. You don’t know them. It’s like you live in a Charlie Brown world.’ I realized she was right.

Paula told me, ‘Try to imagine characters, adults, like yourself. You’re forty years old. You’re not a teenager anymore. Try writing the script as a forty-year-old.’ So I went into creating the character of Paloma as myself, like people I knew, and like my real world at that moment. I had a lot of friends with kids, so I learned from them. It was difficult to imagine adults in the coming-of-age stories of adolescents, but I went into it with an open mind, and I’m pleased with the result.

Guillén: Absolutely. When people ask me about Club Sandwich, I tell them it’s the best coming-of-age story for an adult that I’ve ever seen. You’ve taken the teenage coming-of-age narratives of your earlier films and applied them to an older character. Personally, however, I hope you never lose sight of the gift you have for understanding adolescence. I’m sixty years old, but I’m still a kid, and those narratives still apply to me by odd extension.

Eimbcke: Adolescence is about something you don’t have. You’re not complete. You become an adult and you think, ‘Ah, I’m an adult.’ Yes, you are an adult because you have responsibilities and you own things; but, there’s still a lot you don’t have. You’re an adolescent your whole life. As an adult, you have to be mature, but there is still always something missing.

I have kids now. And when they’re listening to rock music, it helps me listen to rock music with a new ear. For example, I was teaching them about the Beatles and it was like listening to the Beatles for the first time all over again. It was wonderful to listen to my kids learn these songs and sing them out loud, even though they don’t speak English. They just know the music. I think it’s important to read books, watch films and listen to music as if you are a kid; to let yourself be surprised.

Guillén: You say you started out as a photographer and you shifted into being a filmmaker; do you still take photographs?

Eimbcke: Not so much.

Guillén: So the filmmaking has taken over?

Eimbcke: Yes.

Guillén: Your photographic eye, however, is strong in Duck Season, especially with its use of black-and-white cinematography. Alexis Zabé was your cinematographer and you’ve worked with him on both Duck Season and Lake Tahoe, but not Club Sandwich?

Eimbcke: No. I worked with María Jose Secco on Club Sandwich. She’s an amazing young Uruguayan cinematographer. This year alone she shot Diego Quemada-Díez’s La Jaula De Oro (The Golden Dream, 2013), my film Club Sandwich, among others. Her range is amazing. La Jaula de Oro and Club Sandwich are so different from each other visually; they’re like opposites. She adapts to her assignments.

Guillén: The Mexican film industry has evolved rapidly in recent years. Can you talk a bit about your perspective on that evolution? Is it any easier for you to secure financing to make your films? How much do you collaborate with other Mexican filmmakers?

Eimbcke: We collaborate a lot. For example, I’ve read scripts for Michael Rowe and have seen the first cuts of his films. I asked for help from Luis Mandoki, from Carlos Cuarón—the brother of Alfonso—so, yes, there is a lot of interaction between us, which I believe is helpful. The themes of Michael Rowe’s films are quite different from mine, but when he made Año Bisiesto (Leap Year, 2010) he knew me and approached me and said he was a fan of Duck Season and had learned a lot from watching Duck Season, and that he had learned a lot from Alfonso who, in turn, told him he had learned a lot from Duck Season. So films are like a family. That’s not my idea—I’ve taken that from Paula Markovitch—but she showed me that films have a specific dialogue between themselves. This is especially clear in Mexican cinema. The films of Alfonso Cuarón together with the films of Alejandro González Iñárritu have a dialogue with the films of Guillermo del Toro who have a dialogue with my films. It’s beautiful.

Guillén: Are there many government subsidies for filmmaking in Mexico?

Eimbcke: Yes. There’s a tax fund. For example, if you’re Ray-Ban and you have to pay the government of Mexico 10 pesos in taxes, you can take one peso of that and put it into a film. As a filmmaker or a production company, you have to apply to a committee. If your script is good and you have a serious production team ready to go, they will give you this support, but you have to find the company. For example, if I have the script, and a budget, I would approach Ray-Ban and say, ‘Hey Ray-Ban, I want to make this film. Do you want to be a part of it? Do you want to put your tax money into this film?’ Then, if they want to, we apply together to the governmental committee.

Guillén: Who is that government entity? Who makes up that committee?

Eimbcke: It’s made up of directors, producers, people from international festivals.

Guillén: It’s not UNAM?

Eimbcke: No, it’s IMCINE (Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía). The committee also includes Conaculta (Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes). A lot of Mexican filmmakers have used this subsidy.

Guillén: I admire many qualities in your work, particularly your respect for young people, for people from every class, but especially your incredible respect of women. Your respect comes across in your films, which is lovely to witness. I adored the young girl in Lake Tahoe. And, of course, Paloma is a wonderful character in Club Sandwich. But also in Club Sandwich there are a lot of women behind the camera. Can you speak to that? Was that conscious on your part or did it just happen?

Eimbcke: No, it was very conscious. It’s really important. For example, the light of María Secco is really intimate. My cinematographer for Duck Season, Alexis Zabé, didn’t filter out light but María Secco used flats to redirect the light and create a more intimate atmosphere, which was important to me. My editor Mariana Rodríguez have worked together since Duck Season. I enjoy working with women. I prefer a less testosterone-charged work environment. I prefer subtle energy to machismo energy.

Guillén: Let’s talk a bit about casting. You use a lot of young actors for your characters. I’m not familiar enough with the entirety of Mexican filmmaking to know if these young actors are working in other films or if you’re taking non-actors and putting them in their first films; but, as a director, you elicit naturalistic and honest performances from all of them. Can you talk about how you direct young actors? Are they non-actors?

Eimbcke: They’re primarily non-actors; but, not all of them—the young girl Jazmín (Danae Reynaud) had acted before—but, as a director what I like is to adapt myself to the real person. I don’t care if they’re an experienced actor or a non-actor. One of my biggest influences has been Robert Bresson. I love his book Notes on the Cinematographer. He’s dogmatic about using non-actors but I think you can mix actors with non-actors. What I think is most important as a director is that you fall in love with them: how they move, how they talk, everything. In that way you let them be themselves and get the best out of them. For example, in Lake Tahoe I asked the character of Lucia (Daniela Valentine) to make up a song. This was a direction that came in the moment of shooting. It was not something rehearsed. I said, ‘Okay, this is the moment. You have to create a song.’ She said, ‘Do you want to rehearse?’ I said, ‘No, no, no, let’s do the scene and you’ll make up the song in real time. That’s your job.’ I let her do that, I trusted her to do that, because I was in love with her. Everything she did, I liked. The same was true with the characters of Diego Cataño, who I used in Duck Season and Lake Tahoe. If I told Diego, ‘Okay, eat pizza’, I knew he would eat pizza in a lovely way, and that I would love it. The most important thing about knowing if someone is the right actor for a role is that I must fall in love with them.

As for María Renée Prudencio, the woman who plays Paloma in Club Sandwich, she’s a well-known actress in Mexico, but primarily for soap operas for TeleAzteca. She did a huge telenovela called Mirada de Mujer (1997)—you must see this!—and so she is very well-known. But because she is primarily a TV actress, a lot of film directors won’t cast her. I don’t care. An actor is an actor and they can make TV, theater, film, whatever.

Guillén: When you’re writing your characters, do you have particular actors in mind? When you were writing Club Sandwich, were you thinking of María Renée?

Eimbcke: No. In fact, when I was writing the script I made the mistake of thinking it would be played by a particular actress. I told the producers and they got all excited because she was a well-known Mexican actress, and then she wasn’t available so we began thinking about another well-known international actress, but then—when I began casting for the film—she didn’t mix well with the others. So I talked to my casting director Viridiana Olvera and warned her, ‘You will be crazy, mad, after a while because this is going to be a very difficult process. I know that I spend a lot of time making the cast.’ She said, ‘Don’t worry. I won’t go crazy.’ But then, by the end, she was like, ‘Oh my God, you don’t know what you want! You don’t know.’ I admitted, ‘No, I don’t know. But I know the characters and I want to be surprised by the real people who will play them. I want to be surprised by the relationships between them. I don’t know who they are yet but I have to adapt myself to their relationships.’

So when I saw María Renée with Lucio Giménez Cacho (who played the young boy Héctor), that’s when I knew, and I went crazy, because they were like mother and son. I put them through some improvisations to be sure. For example, one improvisation was funny. I told Lucio, ‘Ask your mother for a condom. You’re friends, you have a very special relation.’ Then I told María Renée, ‘You’re a very cool mother so he will ask you for a condom. What will happen?’ We created that scene, and when I saw it, I fell in love with them and knew they were the characters. So casting sometimes takes a lot of time. Sometimes we would find actresses who made great Palomas, but when we placed them with certain Héctors, it just didn’t work, and vice versa. It was complicated.

Guillén: So, clearly, you’re going for the embodied personalities of your characters?

Eimbcke: Yes.

Guillén: And a fit between personalities?

Eimbcke: Yes.

Guillén: And in the audition process you practice with these personalities, placing one personality against the other?

Eimbcke: Yes. Here’s another interesting piece. Lucio is the son of a well-known Mexican and Spanish actor Daniel Giménez Cacho, who was in Blancanieves (2012), among many other films. When I asked Lucio, ‘Do you want to make a film?’, he said, ‘I really don’t care. Let’s do it, but I’m not crazy to do a film.’ That was good because sometimes there are teenagers who really want to make a film and have a lot of energy, maybe too much energy, but Lucio was cool.

Guillén: When I attended the Morelia Film Festival this last year, I was impressed with how fan-oriented it was and how the fans went nuts for the attending talent. I’d never quite seen such fervor before. What do you think filmmaking means to the average Mexican? Do they dream that filmmaking will provide a chance for them to achieve social mobility? Why do you think there is such a love for Mexican cinema?

Eimbcke: The festival itself creates that enthusiasm, that love, because (unfortunately) that fan attitude doesn’t reflect at the box office. We only had two huge amazing blockbusters this last year. One was from Eugenio Derbez called No Se Aceptan Devoluciones (Instructions Not Included, 2013), which was a huge success. Before that there was Gary Alazraki’s film Nosotros Los Nobles (The Noble Family, 2013), which was also a phenomenon. Nosotros Los Nobles was a remake of Buñuel‘s El Gran Calavera (The Great Madcap, 1949). Both films made a lot of money. But except for those two films, most Mexicans don’t care and don’t go to the cinemas to see other Mexican films.

Guillén: So when you make films as a Mexican director, are you presuming that your audience is an international festival audience and not a Mexican audience?

Eimbcke: Yes. It’s not actually a presumption; it’s a sadness. When I make a film like Duck Season, I hope it will talk to people in Mexico, especially all the people who live in the cities, young people, but it doesn’t happen. Mexican audiences complained, ‘It’s in black and white. It’s a festival film.’

Guillén: Is that possibly because Mexican audiences are melodramatically fixated and trained to appreciate telenovelas?

Eimbcke: Yes. This is a very important point because Eugenio Derbez worked with Televisa and became famous through television so that—when he made a film—his television audience came to the cinema.

Guillén: So you made