Before there was Trouble in Paradise or a Design for Living, before Jeanette MacDonald sang or Garbo laughed, before sound even came to the cinema, Ernst Lubitsch was well known for his movies. As an actor on the German stage and screen, colorful posters bearing his image advertised his appearances as Siegmund Lachmann, Simon Pinkus, or Moritz Abramowski. As a film director, a career he began in his early 20s, his slapstick, farces, and costume epics beckoned the masses to the movie palaces of his native Berlin, even as war-weary Germans waged a bloody revolution in the streets. The son of a Russian immigrant, he was the first among the great directors—Joe May, Fritz Lang, G.W. Pabst, F.W. Murnau—to break the wartime embargo against German films. In fact, it was his Madame Dubarry, released in late 1920 in the United States as Passion, that paved the way for the export of many Teutonic masterpieces to follow. But before Hollywood called, before he ever boarded a boat to cross the Atlantic, Lubitsch contributed to the making of more than 70 films in his homeland.

His short films were mostly slapstick and farce and the best of them feature Ossi Oswalda, a cherubic blonde with a mischievous center. The Doll (1919) begins with Lubitsch setting up a miniature of the film’s scenery for his story about a young man who must marry to inherit. At the behest of some greedy monks, the reluctant heir goes to a doll maker (named Hilarius) and requests a life-sized specimen that would fool his uncle into thinking he had found a wife. Lubitsch exposes the foibles and hypocrisies of his characters, gently mocking fat monks chowing on pork knuckles while predicting their own starvation (the monks seek to obtain the boy’s inheritance after giving him refuge), a joke that alarmed American censors enough to ban the film. Oswalda made her career playing ungovernable cherubs, starring in her own comic series and many other Lubitsch films. In his I Don’t Want to Be a Man (1918), she escapes her guardian by dressing like a man. Weimar Berlin, with its gay-tinged cabaret culture, must have reveled in the transgressive images of women pursuing a woman (albeit in disguise) and two ostensible men kissing in public.

The Oyster Princess (1919) is further testament to the charm and comedic skills of both Oswalda and Lubitsch. A parody of the postwar relationship between America and Germany, it centers on the American Oyster King’s daughter, who goes in search of a royal husband to add to her possessions. Rows of lion statues adorn each stair in the conspicuous home of the Oyster King, who has rows of servants to light his cigar and wipe his mouth. His daughter’s escort into the city includes eight unnecessary horses and matching footmen. The European prince, meanwhile, lives in a shabby garret and has to borrow money for a night out on the town. Delight is the ultimate point of Lubitsch’s film: In an extended set piece, a foxtrot “epidemic” spreads to the household staff. Extra prints of the hour-long film had to be struck to meet domestic exhibition demands.

Founded to aid the German propaganda effort in the tail end of WWI, Ufa studios primarily valued Lubitsch for his epic costume dramas, which, when exported, generated desperately needed foreign currency. By the time he made his first, The Eyes of the Mummy Ma (1918), the director had cultivated a dedicated cast of players, including the handsome leading man Harry Liedtke, Emil Jannings, whose range extended from ham to high drama, and Margaret Kupler, who appeared mostly as governesses or old maids. He had also gathered around him an expert array of artists and technicians, among them art director Kurt Richter, photographer Theodor Sparkuhl (who later shot William Wellman’s Beau Geste, among other Hollywood films), costume designer Ali Hubert, and Hanns Kräly, who not only wrote or adapted most all of Lubitsch’s German output but also accompanied him to Hollywood where worked on a string of Lubitsch pictures.

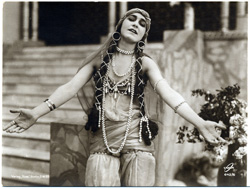

The Polish-born actress Pola Negri was Lubitsch’s most visible collaborator, appearing in six of the films he made during 1918–1922. Based on the Prosper Mérimée novella about a hot-blooded gypsy with commitment issues, Carmen was Lubitsch’s first international success. A preview screening for the film took place the night before Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated, the night revolution broke out on Berlin’s streets. “There was applause at my first appearance,” Negri recalled years later, “Over it and lingering for just a moment after I heard a faint sound in the distance … gunfire.”

More cast-of-thousand epics followed. Starring Emil Jannings as the simultaneously lecherous and puerile Tudor tyrant and Henny Porten as the doomed second Queen of England, Anna Boleyn (Deception, 1920) was the most expensive German film to date. It was such a big deal that the president of the Weimar Republic paid a visit to the set during one of the major outdoor shoots. Friedrich Ebert and his entourage were spotted by the swarming 4,000 underpaid extras and, instead of a wedding procession, Lubitsch shot a near-riot.

Delight is the ultimate point of Lubitsch’s ‘The Oyster Princess’: In an extended set piece, a foxtrot ‘epidemic’ spreads to the household staff. Extra prints of the hour-long film had to be struck to meet domestic exhibition demands.

Traces of his famed light touch can be found throughout his German films, in both the broad comedies and historical spectacles. In The Wildcat (1921), a fairy-tale send-up of military life set in the Bavarian mountains, a band of brigands raid a military fortress during a party, but the thieves succumb to the festive music and set about dancing rather than marauding. Their ultimate booty? Warm underwear. It is there in his adaptation of Friedrich Freksa’s pantomime Sumurun (One Arabian Night, 1920), which features a Greek chorus made up of matronly eunuchs dressed in fezzes and strapless tunics tsk-tsking their way through the film. Even amid the tragedy of Anna Boleyn, it rears its subtle head. Henry VIII meets his new mistress because her dress gets caught in a door while she’s shyly fleeing from him.

Writing in 1947, Lubitsch said his goal with his historical epics had been “to de-opera-ize the contemporary film versions of history. I considered the intimate nuances just as important as the mass scenes, and I tried to mix the two.” As spectacle, they exhibit a complete mastery of form, as accomplished as any similar film by Pastrone, DeMille, or Griffith. They are often much better, as he weaves in comedic subplots and makes use of the whole frame to move the plot along against the outsize backdrops, whether the medina, a Tudor palace, or revolutionary France. In Sumurun, for example, a carnival hunchback (played by Lubitsch in his last movie role) entertains an enormous crowd while, in the background, Pola Negri’s character can be spied in a swoon over her latest conquest.

A complete career by anyone’s standards, his German silents were only the beginning. Working at United Artists, Paramount, Warner Bros., and MGM, Lubitsch made many memorable American silents, among them an adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windemere’s Fan (1925) and The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg (1927), starring Norma Shearer and Roman Novarro. He then went on to pioneer the musical and then to invent the American romantic comedy. Describing Lubitsch’s films as “elliptically naughty, witty, and insouciant,” Bogdonavich wrote in 1983 of the German émigré’s impact: “Directors as disparate as Hitchcock, Hawks, and Chaplin learned from him; and anyone who ever made a comedy from the ’20s until about a dozen years ago sought to capture even a quarter of the magical charm Lubitsch always had working, no matter who the players. His famous ‘Touch’ was feather-light and profoundly compassionate; he understood his people and loved them during every moment he showed us how foolish they were.”

Shari Kizirian writes from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and coedits the program book for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival.