A living film-history diorama, a scattered jumble of po-mo genre exercises, a slackly bound compendium of a decade’s worth of ideas, Leos Carax’s Holy Motors is so bedecked in influence and allusion that it might easily be mistaken for something trite and frivolous, a free-associative fantasia without any actual substance. It might be just that, were the film’s seemingly random collection of individual sketches not bound by a concealed casing; rigorously concerned with the effects of digital filmmaking on both his own process and the world at large, Carax ends up reconnoitering the increasingly imperceptible border between “real” life and the realm of copycat performance.

The divide between these two spheres has always been a point of fascination for the director, linked to his steady reliance on reference-heavy pastiche. Hollowly ambitious knock-offs tinged with fleeting moments of virtuoso brilliance, his films often involve characters struggling to escape nebulous shackles: a paternal criminal legacy in Bad Blood; society, disease and family authority in Lovers on the Bridge, the dual prisons of upper-class decadence and Pialat-style dissipation in Pola X. These struggles mirror Carax’s own, primarily the difficulties of a young director trying to distinguish himself in the towering face of All That’s Been Done Before (not to mention financing issues, which have plagued him relentlessly). Carax responded to these threats to originality by plunging fully into a heavily referential, highly romantic form of nihilism, an approach defined by a hodgepodge visual style connected by a thin thread of weary misanthropy. His movies teeter at the brink of the broad pit of cinema history, teasing a simulacramatic void that threatens to consume them completely.

Carax’s signature conflicts find their fullest expression in Holy Motors, which integrates the director’s struggles into the film’s own central structure, following a character doomed to recreate scenarios dreamed up by others, a Protean roundelay of transformations performed at the mercy of unseen surveilling forces. After years of employing eponymous protagonists (Leos Carax is a reshuffling of the director’s birth name, Alex Oscar) Carax has finally unleashed a character whose plight runs parallel to his own, searching desperately for truly-felt experience within the cracks of an oppressive system of pantomime and facsimile. The resulting film is a postmodern puzzle box—vivified stock characters roaming about in fetters, trapped inside nested levels of observation—as well as a distorted reflection of a world where every action is recorded and every pose is lifted from somewhere else, forming a complete circuit between influence and performance. The pairing of these ideas with a neatly honeycombed structure makes for Carax’s first wholly successful feature since Boy Meets Girl, his debut, another film narratively and formally concerned with the oppressive shadow of the past.

‘Holy Motors’ recalls the mid-career transition made by Godard, another bad-boy pastiche artist who graduated to a more interestingly assaultive approach, spinning his love for cinema into its own unique form of production.

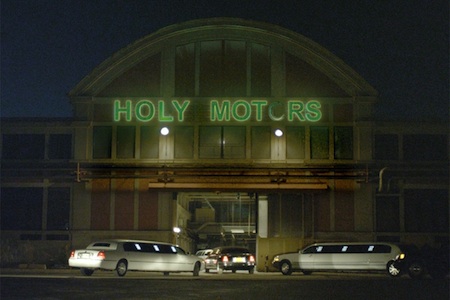

To summarize Holy Motors’ largely inexplicable plot: Professional chameleon M. Oscar (Denis Lavant) leaves his stark modernist home (shades of Mon Oncle, for those keeping track), waves goodbye to his scores of children, and enters his limousine-cum-dressing room, where he prepares for the first of many open-ended acting assignments, assuming the shape of a withered crone begging on a Paris street. The film progresses from one such sketch to another, broken up by short intervals in the limo, where Oscar chats with his driver (Edith Scob), snacks on sushi and is eventually reprimanded by his mysterious employer (Michel Piccoli). The last of these exchanges is the most significant, since it’s where we’re apprised of the rough outlines of the game being played, which involves tiny cameras capturing all this bizarre street theater for the benefit of invisible observers.

In this world the limo appears to be the only area not subject to constant scrutiny, and even this haven is chockablock with disguises, costumes and materials, less a respite from a monitored demi-reality than the engine from which the drama draws its power. This lack of shelter is key, as is the fact that the limo’s glass is tinted; Carax has always used two-way reflective surfaces as the medium between the worlds of pure influence and real life, a prevailing system of porous borders which reflect, capture and transform the images passing through them. This is the dominant visual symbol in Boy Meets Girl, Carax’s first and heretofore purest expression of the perils and pressures of pastiche. An ostensible love story, the film is less concerned with issues of plot and character than creating a glittering kaleidoscope of mirrors, windows, rivers and puddles, presenting off-kilter copies of familiar scenarios (the party scene in Pierrot le fou; Maria Falconetti’s pained gazes in The Passion of Joan of Arc, the through-the-looking-glass world of Cocteau’s Orpheus) that thrive on their uneasy similarities to their forebears.

Many ambitious filmmakers start off with this kind of gushing tribute to their inspirations, but for Carax the initial exorcism never fully took. All his films are defined by incessant reference and dominated by their relationship to previous works, even when they’re pretending to be about other things —as the protagonist of Bad Blood expires from a gunshot wound, his death is presided over by a dog identical to the one in the last scene of Band of Outsiders, a distracting Easter egg that further diminishes the payoff of an already weirdly conceived scene. His three middle movies, while fitfully brilliant, have their overall impact attenuated by Carax’s obvious boredom with traditional storytelling strictures. When their purposely derivative stories drag, the director entertains himself by staging startling bursts of performative excess: the Modern Love tracking-shot dance in Bad Blood, the water-skiing and fire-breathing scenes in Lovers on the Bridge, the descent into the anarchist commune in Pola X. These are invariably the most memorable sequences in these films, because they’re the ones in which Carax is truly expressing himself, via furious cocktails of reference and originality heaved Molotov-style at the audience.

The conduit for most of these outbursts is Denis Lavant, Carax’s career-long muse, a chunk of human silly putty with a uniquely convulsive style of movement. A cross between Quasimodo and Fred Astaire, Lavant makes art out of stricken disquiet, functioning as both the director’s twisted avatar and a further extension of his reflective surfaces motif. The absorption of so much prior material may only cause Carax’s worlds to seem slightly warped, but this heaviness (the so-called “cement” filling his stomach in Bad Blood) has more serious consequences for Lavant’s characters, leaving them spavined and morose; it’s probably no coincidence that the period from Boy Meets Girl to Lovers on the Bridge finds his characters, all named Alex, progressing from scruffy but fresh-faced naïf to wretched street wastrel. Meanwhile, Lavant’s blank-slate form and physical dexterity make Holy Motors possible, his body acting as a physical analogue for the endless possibilities of digital, a format which Carax claims to despise (he’s described the movie as a stopgap measure to raise funds for his return to physical film) but actually seems to view with the same mixture of distaste and compulsion as he does his historical influences.

This ambivalence is what makes Holy Motors such a spectacular creation. A temper-tantrum for the death of physical media and private lives, it bemoans a world where everything can be boiled down to performance, while also marveling at the conditions that allow all this rapturous action to be captured. It’s Carax’s best film because, instead of just being plagued by the grave burden of cinematic history, it’s entirely about that burden, possessing a structure in which the referential baggage can’t overwhelm the story, because it is the story, an anthology of wild set pieces that don’t have to bother with the tedious gristle of a coherent narrative. Inserting faint glimmers of plot at the creases between its performances, Holy Motors functions like a traditional movie musical—uneven by design—the consequence of a world where all behavior exists on the same performative plane, where the private scene of a father berating his daughter and the motion-capture spectacle of graphic dragon sex both pull from the same bag of costumes.

The film’s structure liberates Carax. He strings together a daisy-chain of unrelated incidents, borrowing the construction of Robert Coover’s A Night at the Movies, with its anarchic distillation of familiar tropes, turned foreign by their newfound coexistence. This emulsive method takes ideas that might be questionable on their own (a live-action entra’acte, brought to life by a stomping, accordion-heavy marching band; a glaringly obvious nod toward Eyes Without a Face, which leads into a coda involving talking cars; a demented sewer-dwelling leprechaun sporting a full-bore erection) and heaves them at the screen like paint. The synthesis from the flashy, knowing appropriation of his previous movies to the circuitous, gonzo anarchy of Holy Motors recalls the mid-career transition made by Godard, another bad-boy pastiche artist who graduated to a more interestingly assaultive approach, spinning his love for cinema into its own unique form of production. Carax is still a long way from the level of the French arch-master, but while he may view digital as a mere means to an end, the format has clearly inspired him to adopt a new system for handling his influences, one which finally allows him to work on his own terms.