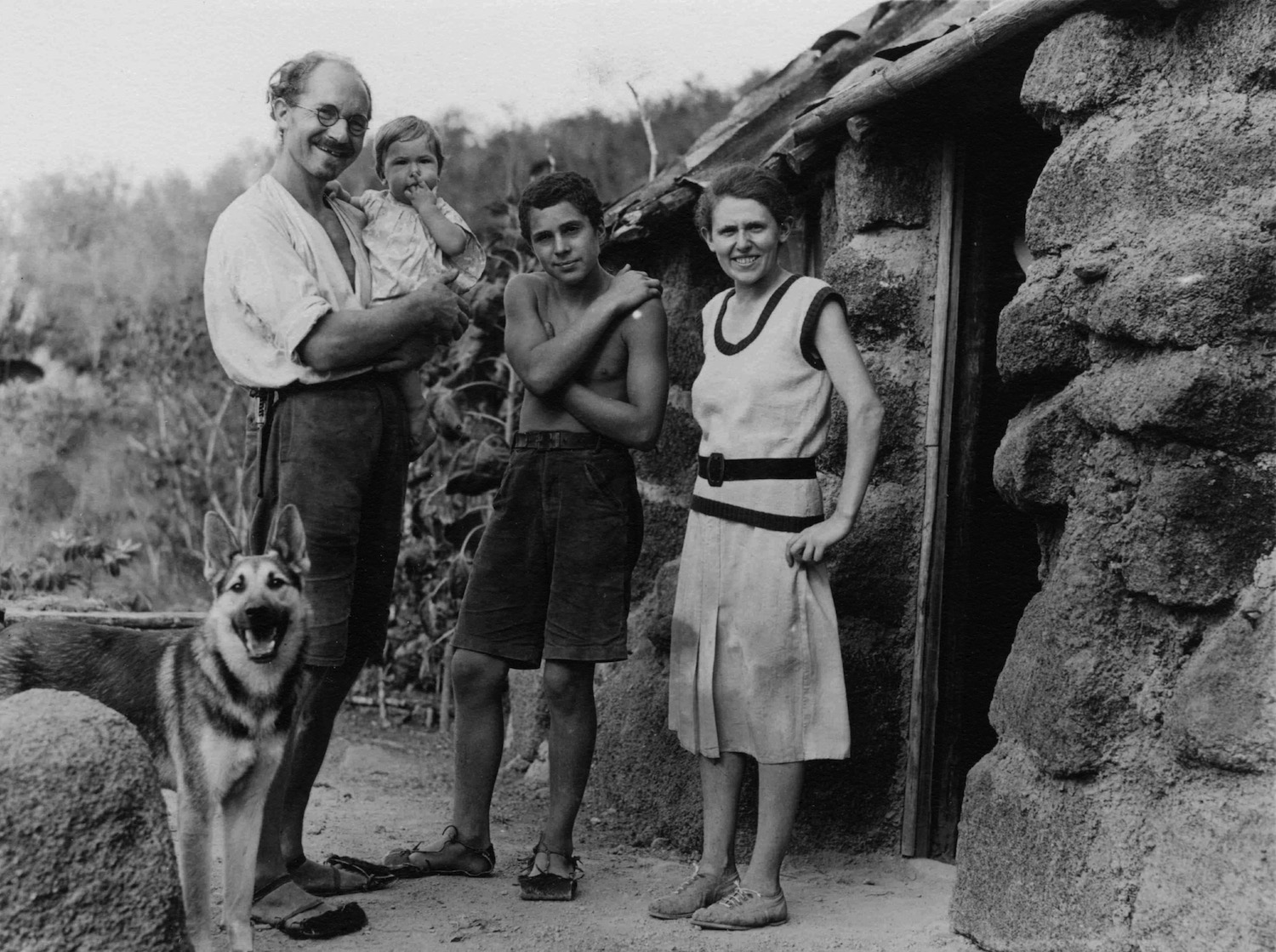

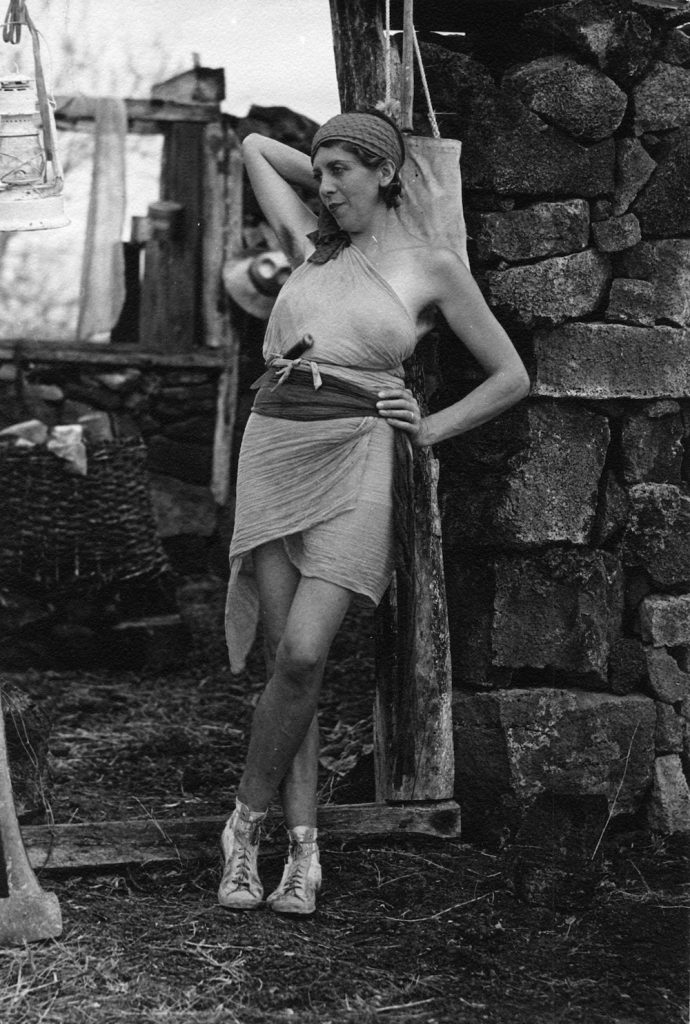

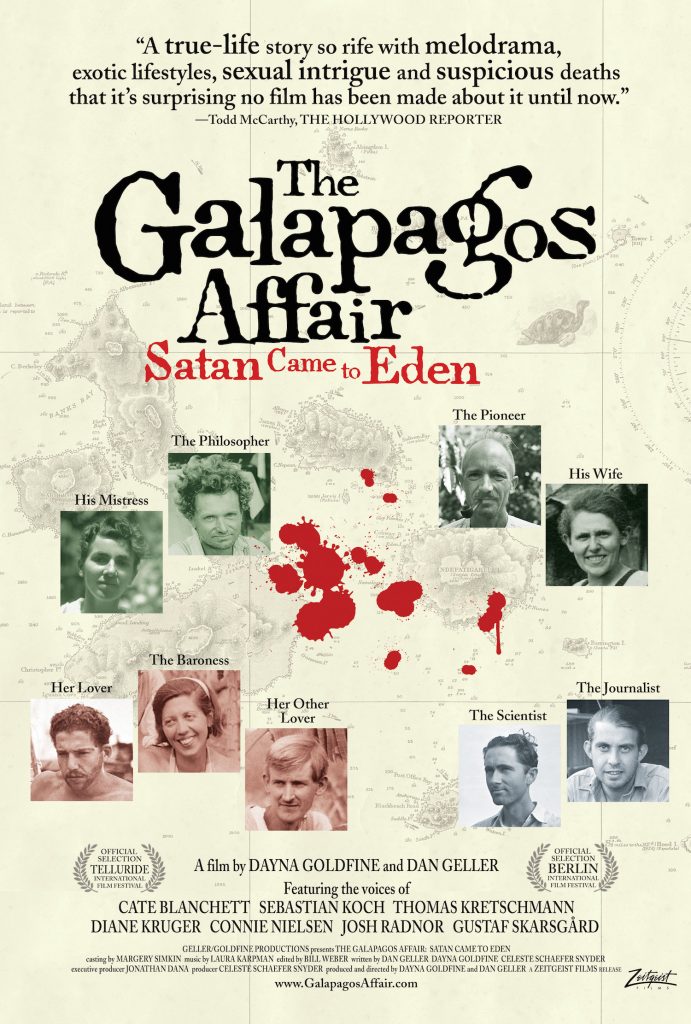

Darwin meets Hitchcock in Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller’s fascinating documentary portrait of a 1930’s murder mystery, The Galapagos Affair: Satan Comes to Eden. Fleeing conventional society, a Berlin doctor and his mistress start a new life on the uninhabited Floreana Island, but after the international press sensationalizes the exploits of the Galapagos’ “Adam and Eve”, others flock to the island, including a self-styled Swiss Family Robinson and a gun-toting Viennese Baroness and her two lovers. The filmmakers (as Michael Fox has already written here) interweave newly unearthed home movies from the original settlers, testimonies of modern day islanders, stunning HD footage, and voice performances by Cate Blanchett, Dian Kruger, Connie Nielsen, Sebastian Koch, Thomas Kretschmann, Kustaf Skarsgård and Josh Radnor to create a gripping parable of a Robinson Crusoe adventure and utopian dreams gone awry.

For over twenty years, Emmy-award winning directors/producers Geller-Goldfine have jointly created critically acclaimed, multi-character documentary narratives that braid their characters’ individual personal stories to form a larger portrait of the human experience. Their award-winning film Something Ventured (2011), premiered at SXSW, went on to play at festivals internationally, and was broadcast nationwide on PBS. Geller and Goldfine’s work also includes: Ballets Russes (2005) which was recognized as one of the top five documentaries of 2005 by both the National Society of Film Critics and the National Board of Review and appeared on a dozen critical “10 Best Films” lists, including those of Time Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, The Hollywood Reporter, the San Francisco Chronicle and Slate; Now and Then: From Frosh to Seniors, which premiered theatrically in October 1999 and aired on PBS in October 2000 as the lead program of the Independent Lens series; Kids of Survival: The Art and Life of Tim Rollins + K.O.S. (1996), a feature-length documentary about the South Bronx-based art group Tim Rollins & K.O.S., which aired on Cinemax in September 1998 and was the recipient of two national Emmy® Awards; Frosh: Nine Months In A Freshman Dorm (1994); and, the award-winning Isadora Duncan: Movement From the Soul (1988). The duo agreed to meet me mid-afternoon at Mojo Café on Divisadero to discuss the craft behind their captivating documentary hybrid.

Keyframe: Can you speak to your documentary impulse and why you choose to film documentaries over narrative features?

Daniel Geller: First of all, I have this bugaboo that for some reason fiction films are called narrative and non-fiction films are documentary. If you go into a bookstore, it doesn’t say narrative and non-fiction. The assumption would be that if a book is good it has a narrative, in fiction or non-fiction. A lot of the independent theatrical documentaries from the last ten to fifteen years have moved away from the tired constructions of TV formulas to something that is much more story-driven, and character-driven as well. That’s more compelling to an audience.

At the same time, a lot of the ‘larger’ movies for financial reasons have drifted towards telling the same story over and over; but, the other thing is that there are these independent fiction films—relatively independent, like what the Coen Brothers are doing or what David Russell has recently done, among others, or Woody Allen for that matter—that are stories that are interesting and breaking ground. Those are more directly aligned to the documentary impulse to get into someone’s mind to find an interesting story about somebody’s life.

Dayna Goldfine: What’s interesting with regard to the Oscar race this year is that a huge number of the fiction films are based upon true stories: Dallas Buyers Club, Captain Phillips, American Hustle, The Wolf of Wall Street, Saving Mr. Banks. To a certain extent, there’s a grain of truth in all of those. It’s interesting that—not only in documentary theatrical films—but in fiction theatrical films at least this year so many stories are based upon true stories.

Keyframe: I accept that; however, I still believe documentary tells the true tale better. What I’ve noticed about documentaries over the years, though—and why I didn’t like documentaries when I first started watching them—is that they’re predominantly issue-driven and not artful and that, sometimes, especially if the issue is particularly strong, there doesn’t seem to be any need for artfulness. Where I must commend the two of you is in the compelling artfulness of your documentary.

Goldfine: Thank you. That means a lot.

Geller: Thank you. We aim to do that. We try. We never know if it will work, but that’s definitely the impulse.

Goldfine: This year’s Oscar entries The Square and The Act of Killing are both issue-oriented films but they’re both done so artfully that they’re a giant stride forward in the documentary form. This almost seems like the first year where I’ve seen more than one documentary nominated where you could really make an argument that it was a piece of art, as well as being political.

Keyframe: So before we begin to discuss the craft of how you constructed Galapagos Affair: Satan Comes to Eden, I have to ask a hard-hitting question. [I lean forward and stare directly at Dayna.] Dayna, did you pull the spark plug on the boat so that you would land on Floreana Island?!! [Laughter.]

Goldfine: Psychologically? If there was a poltergeist, I was challenging that poltergeist to come forward. Our friend who had hired us was so annoyed with me before it finally happened. He couldn’t believe that I kept at him every single day about going to Floreana. I didn’t know it then—though I do now since we’ve been there so many times—but the boat trip is circumscribed by the national park. You can only really go to the islands that they say you can go to. Then, I had no idea. So when we broke down alongside Floreana Island, he literally stormed into our cabin and accused me of sabotage!

Keyframe: Your previous film Ballets Russes was simply magnificent, as was Galapagos, and what I might say about both of them would be framed within the Amerindian concept of the long body. Are you familiar with the concept of the long body?

Geller: No. Say more.

Keyframe: My most immediate understanding of the long body is when a young person is sent on a vision quest, with one aspect of that quest being a search for ancestors, and another being a visualized projection of who they will literally be when they are older. The long body acknowledges the span of a lifetime within generations of lifetimes. I noticed that both Ballets Russes and Galapagos start in the 1930s and progress into the contemporary era. This makes sense, of course, as there would still be living agents who could speak to the original narratives. But can you speak to your personal interest in these kinds of life arc narratives?

Geller: Well, the longitudinal narratives are really interesting, especially in a documentary, because—if you stick around long enough in anybody’s life or look back on someone’s life—you’ll find dramatic movement. This even applies to films like Kids of Survival where we shot for three years in the South Bronx in that workshop with the kids. A lot happened over those three years that would not have happened if we had just dropped in for four weeks of shooting and then left.

Which also addresses your point of how documentaries are becoming seemingly more artful. Filmmakers are not writing scripts and then going in to back them up with images. It’s the other way around these days. We’re exploring a topic, or exploring a human character, and then taking however much time we need to make it work. It was the same with Frosh (1994): nine months we lived in that freshman dorm. So it does become a question of time. Ballets Russes and Galapagos have this other aspect, which is a huge amount of available visual material. To access the pictorial record of someone’s life is an amazing privilege and that’s something we’ve only really had in the last 100 years or so where you can see someone’s physicality from youth to old age. There’s something powerful, poignant, and wistful about that, which adds a layer of emotion.

Goldfine: Even though Dan and I make these films together, we come up with something at the end that we both feel passionately about; but, for me, it was more of a conscious transition. Not that I would never go back to making a coming-of-age film like Frosh or The Kids of Survival or Now and Then. We had made those three films and right around the time I turned 40 we started thinking about doing Ballets Russes. I realized, first subconsciously and then consciously, that I needed to do some work about looking for role models in the aging process. I think the only way you can do that is to do the long body, as you call it. It was satisfying to do those coming-of-age pieces, but starting with Ballets Russes and continuing into Galapagos, it felt important to look at the whole life story and to look for people who were fortunate to be 70, 80 or 90, like the Ballets Russes dancers, or some of the people in the Galapagos. I hope my life will have been lived as richly.

Keyframe: Allow me to pursue two points. First, you say that nowadays you’re no longer writing a script but exploring more the unfolding material; in other words, developing narratives through accretion. Secondly, you mentioned using archival material to emotionally texture a documentary. The access to this archival material is indeed astounding in and of itself; but, my question regards your craft in making it interesting to a movie audience. How do you decide to present the archival material? When do you decide to animate a still photo? Can you speak to those decisions?

Geller: It’s always a question of rhythm, timing, and the musicality of the moment. Those decisions are partly driven by how to re-experience a photograph in this funny temporal medium where you can’t just stand there and look at it for however long you want. Some guidance is appreciated, right? To bring your eye around through the story in a fabulous photo. We have so many beautiful photos. They’re not our photos. Someone else took these beautiful photos and we’re trying to bring the most out of them in our funny little temporal medium.

There’s also the question of how much time do we need to allow the voice that’s associated with a story that’s being told at that moment that influences your perception of the image? How much time does that require? The pacing of these decisions is sometimes based on the sheer musicality, but some of it is allowing the thought to be told in voiceover and allowing time for it to be absorbed. It’s a little dance almost between those two factors.

Goldfine: It’s also about asking yourself from the moment you select a photo: to what do you want to draw the audience’s eye? There are so many elements in a photograph. I do need to give Bill Weber, our editor, some credit because a lot of those camera moves he came up with in the editing room and we went along with them.

Keyframe: Once you’ve shot your film, how involved are the two of you in the editing process?

Goldfine: Very. I’m sure if you talked to Bill, he’d say too much. [Laughter.]

Geller: With Galapagos, we were writing the movie as we were editing the movie, in a way. We had all these primary sources—we had Margaret Wittmer’s book (Floreana: A Woman’s Pilgrimage to the Galapagos, 1959), we had journals from John Garth, we had Dore Strauch’s book (Satan Came to Eden, 1935), we had articles and newspapers, which formed this first person dialogue among the characters. We would write it sitting there with our right hand Celeste Schaefer Snyder, and often with Bill (even though Bill said he couldn’t stand the writing anymore and would send us off to write any given chapter). That’s pretty much how we did it, by chapter, and we would bring back the script and work through that with Bill. He’d show us a version of what he’d cut and then we’d look at the script again and say, ‘You know, we need to rewrite that script.’ We’d either need to take someone out of that flow of dialogue or change the wording slightly to give a sense of clarity that might not have been added to the original article from which we took our quotes. It was very iterative that way.

Goldfine: Before we decided that we had to bite the bullet and write the murder mystery script—we’d never really done something like that before—we spent a lot of time going back and forth, cutting sequences with the modern characters, and then easing them in to work with the archival stories. We were already about six months into the editing process when we looked at each other and said, ‘We’re never going to accomplish this film and solve the structure of the film if we don’t first build the mystery sequences.’ Once we had that arc, then we were able to begin figuring out where the modern characters fit. But it took a lot of trying to do both at the same time and finally just throwing up our hands and saying, ‘Okay. We have to write this script.’

Keyframe: So therein you’re already melding expected documentary tropes with narrative feature tropes, which you further achieved through your use of voiceover. Can you speak to casting your voices? You have a Hollywood dream cast!

Goldfine: Talk about luck! It was luck that our boat broke down in front of Floreana….

Keyframe: [Suspiciously, with a raised eyebrow] It didn’t sound like luck….

Goldfine: [Laughs.] Okay, it was luck that our friend hired us to go to the Galapagos.

Geller: [Laughs.] It was luck that you weren’t discovered pulling out the spark plug.

Goldfine: Okay, okay. But it was really luck that Woody Allen chose to film Blue Jasmine in San Francisco right at the time that we were ready to start seriously thinking about casting, and that someone who we had become very close friends with in Sydney through the Ballets Russes film had gone to work for the Sydney Theatre Company and was the E.D. to Cate Blanchett and her husband’s artistic director. It was sheer luck that those things happened to draw Cate to our film. It was further luck that Cate liked us and our film.

Keyframe: So the narrative structure had been completely outlined by the time Cate read it?

Geller: Largely, the film was intact.

Goldfine: When Cate was in San Francisco a year ago August, we had the two and a half hour cut.

Geller: There was still work to do on the script but the whole story was in place and Cate could sense that and feel the movie. We didn’t ask her at that time to be in the movie. She had become a friend and we respected her too much as a friend. We thought it would be too awkward to approach her so we decided to just let it be. She gave us wonderful feedback and we accepted that as enough. We didn’t want to trade on our friendship.

Another weird bit of business was how we wound up with our casting director. Jonathan Dana, our executive producer, was at an industry screening in Los Angeles and right in front of him sat this woman who he hadn’t seen in a year or two, Margery Simkin. Margery asked Jonathan what he was up to and he told her he was working on this film with me and Dayna. Turns out, Margery had been to the Galapagos in the late ’80s and Margery had met Margaret Wittmer!

Goldfine: In fact, her boat had also broken down in front of Floreana!

Geller: Margery said that she wanted to do this project. So when we met with Margery and I offhandedly said something about Cate, Margery moreoreless said that the only way she would continue with the project was if we went back and figured out a way to ask Cate. We thought, ‘Oh, God! Now what do we do?’

We called our friend Patrick, who had introduced us to Cate, and asked, ‘Patrick, what would you do?’ We weren’t meeting her to make her do a movie; we were meeting her because Patrick had raved about her and said that she is who she seems to be: a smart, wonderful, interesting, fabulous person. Well, we didn’t hear back for a couple of weeks and we thought, ‘Oh, we really put Patrick into a corner too just now, didn’t we?’ He wrote back and said that he had decided the smartest thing would just be for him to ask if she would be at all interested. And that opened the door. She was interested, right off, and we made it work.

Once Cate came on, then casting became a lot easier. Margery could start proposing different actors to go after their agents to figure out if it was at all possible, for timing and schedule mostly. And that’s how this dream cast came together. It was amazing.

Goldfine: We pretty much suggested the other six actors to Margery and she came up with Josh Radner. I’m really happy that she did.

Keyframe: Give me a sense of this, then: you’re documentarians but you’re directing a Hollywood cast. How do you do that?

Goldfine: Well half of great directing is to choose the right cast member. You don’t even really need to direct if you have the right cast member.

Keyframe: Would you run footage that they would look at and voice over?

Goldfine: We didn’t do it to time. We actually told them all.

Geller: They had all seen the rough cut.

Goldfine: Initially, when we actually started talking to Cate seriously about doing the film, we felt that the best we could do for her was to cast her as the Baroness, because it was a small part and wouldn’t take her much time. But then as we started actually having this phone call with her, we looked at each other and were like, ‘We think she’s actually saying she will do Dore Strauch!’

Keyframe: Dore is the root of this narrative.

Geller: She is!

Goldfine: So when she said that, we were like, ‘Okay, okay, if you will do Dore Strauch, we will fly to Sydney to record you.’ But with some of them, like Thomas Kretschmann, Sebastian Koch, and Gustaf Skarsgård, we had to direct them through SKYPE. They had all seen our rough cut with our horrible acting….

Keyframe: Ah, you did the original voiceovers?

Geller: Yeah. Dayna was Dore. I was Dr. Ritter. Bill was Heinz Wittmer and John Garth. Dayna was also the Baroness. Celeste played Margret Wittmer. We were a cast of terrible actors.

Goldfine: One of the most excruciating moments I’ve ever had in the last several years was to sit next to Cate Blanchett as she was listening to me doing the voice that she was supposed to do.

Keyframe: If I ever interview her, I’ll ask her what she felt in that moment.

Goldfine: Okay! But you know what? She’s such a sweet human being that she’ll be incredibly generous and say I was good.

Anyway, they had seen the footage but we also told them that we didn’t want them to look at the footage while they were recording because we wanted them to give the voiceover its own breath, time, and meter.

Keyframe: Interesting. You trust your actors’ articulate rhythm of the primary source material? And then edit and shape around that?

Goldfine: Exactly. Like with Josh Radnor, we talked a lot about the 1930s, the movies, how the men were all ‘Aw shucks’-ey. What John Garth’s character was, if you read his journals, was someone in his late twenties early thirties, and definitely someone of that era, of the 1930s, who hadn’t yet seen a lot of ironic things in the world. We showed Josh the scene from All Quiet On the Western Front where the men are standing around the hospital bed, trying to ‘aw shucks’ away the fact that this guy’s leg’s been amputated. Josh looked at that and said, ‘Okay, I get it. It’s the pre-ironic moment in time.’

Geller: In terms of directing really fabulous actors, I have two quick stories. First, going way back to our Isadora Duncan film, Julie Harris did the voice of Isadora. So the first film we made had a first person acting performance. Julie came into the studio. She had marked up her script fairly well and read so beautifully and wonderfully as Isadora. There was only one direction we had to give her: an anticipation moment when Isadora discovers she’s pregnant out of wedlock. Julie thought that was a problem for Isadora as a dancer and what it would do to her career. We said no, if you actually read the literature, it was one of the greatest moments of her life. Boom, on a dime, she turned the performance around.

The other was Connie Nielsen as the Baroness. When we sat down and recorded her here in the studio, she asked a brilliant question. Was the Baroness a narcissist who only loved herself? Or the kind of narcissist who wants everyone to love her? It was a wonderful question for an actor to ask because it could color the performance one way or the other. We said, she wanted everyone to love her and boom, off she went. So there’s not a lot to direct at that point.

Goldfine: It’s true, and even though the Baroness had maybe 15 lines in the whole film, we spent a good hour talking to Connie about what kind of a human being the Baroness was.

Keyframe: I agree that’s a brilliant and important question to ask about possibly one of the most fascinating personalities ever presented on film! I was stunned by this woman, the Baroness. What a force of nature!

What I love about your films—specifically, Ballets Russes and Galapagos—is your understanding that the only true narrative is human nature. By contrast to Ballets Russes, which had a cast of hundreds, in Galapagos you honed the cast down and through a limited ensemble expressed so much about human nature.

Goldfine: I love that you think we honed it down! Thank you for that! Because one of the problems one of the fiction scripts has is that it can’t handle the number of characters we managed to juggle.

Keyframe: Basically, the whole first section of the film is only two people.

Geller: Right. And they’re archetypes. Straightaway, they’re so distinguished.

Keyframe: And already there’s tension there.

Geller: Yes. But what was tricky about that was weaving in the modern characters—what we call the modern characters (some of them were born in the 1930s)—that was where we had the hardest time. We really wanted them to be a part of the movie, to expand the notion, the feel and the psychology of the movie, but how to add all those extra characters in and to do it succinctly tracked back to a lot of the problems we were having with Ballets Russes, very similar. How do you introduce a character three quarters of a way into a movie and not exhaust an audience? But even though we were back with the same problems, they were not yielding to the same solutions.

Keyframe: Though I respect and, of course, acknowledge the addition of the modern characters, that’s not what I’m focusing on. I’m thinking about the original core of characters from the 1930s that truly make up the anchor of this narrative. What fascinated me was that—within that core group—everything about human nature was being expressed.

Geller: That’s right. Early on, we knew this story was more than a murder mystery. It’s about the question: ‘What is Paradise?’ What if your notion of Paradise—even if it’s in some way achievable—conflicts with somebody else’s notion?

Goldfine: What struck me immediately was the need of everyone—not just these characters—to mythologize themselves. In other words, every single person that came to that island had developed a myth about themselves and was living it out. Ritter and Strauch were very much the Adam and Eve and they came to Floreana with that sense of mythology. Then the Wittmers came in liederhosen; they were like the Swift Family Robinson. All of these people were, I would say, consciously living out these myths. Because at the time the world, the press, was already identifying them this way. Ritter wrote a three-part essay for The Atlantic Monthly published in 1931 wherein he himself used the terms Adam and Eve.

Keyframe: I’m aware that you recovered the archival footage for Galapagos in Los Angeles in extremely bad condition. How involved were you with the process of film preservation?

Goldfine: They were kind enough to let us bring this frail 16mm footage to San Francisco where we worked with John Carlton at Monaco to engineer its digital transfer.

Geller: We did a fair bit of that on Ballets Russes too with these archives that would pop up out of some closet in somebody’s house. The arrangement has always been that we would give a digital copy to the institution or the person who was kind enough to give us the use of the footage in the first place.

Goldfine: The bulk of what we were working with were the 16mm reels, but we also preserved a lot of the still images. Those rot in archives as well.

Keyframe: And here I have to compliment your editorial wizardry in how you placed this archival footage within the grand narrative of your documentary. Specifically, as I was watching the first sequence about Ritter and Strauch arriving on the island and their first isolated weeks there, I kept thinking, ‘Who’s filming this?’ If they were supposed to be alone on the island, how could anyone be filming them? Of course, the footage was taken by one of the expeditions that later visited them on Floreana, but as filmmakers you didn’t tell us that. We didn’t know about the visiting expeditions yet. I’ve got to say that was a clever manipulation of cognitive dissonance and chronological displacement.

Goldfine: We definitely went through this dialogue where we asked whether we needed to make that clear up front but we ultimately decided not to. It might have been more documentarian….

Geller: But it would have taken you out of the moment and would have interfered with the narrative of two people on an island without anybody there. And look, part of what we set out to do from the beginning was to make a weird movie, at least slightly weird. In the past we’d never set out to make a weird movie, so we thought that would be part of our aesthetic challenge: to make it slightly off balance, which suits the subject of course. It suits the people who are in the movie. They’re all off a little bit. Some of the weirdness of the movie feels like a reflection.

Keyframe: And, of course, it suits the film’s central mystery. When you spoke to Scott Foundas, you admitted to borrowing foreshadowing from Hitchcock to amplify the film’s mystery. You don’t feel in any way that this undermines the documentary impulse? The true story?

Geller: A story about unreliable narrators self-mythologizing the fabulous? What is the truth in all that?!