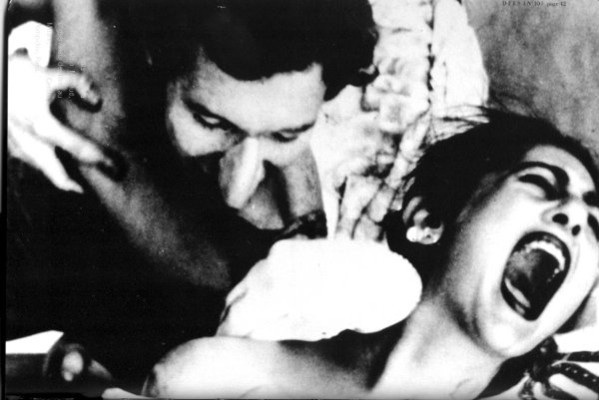

Gregory Markopoulos is one of the truly mythic figures of the American avant-garde. He directed his first serious movie, the spellbinding Psyche (1947) as a teenager in Los Angeles where he roomed with Curtis Harrington and studied with Josef von Sternberg at USC. Back in his hometown of Toledo, Ohio, Markopoulos made two additional installments of the Du Sang, de la volupté et de la Mort trilogy (Lysis and Charmides, both 1948) in addition to several other lushly romantic shorts. To watch something like Swain (1950) today is to be impressed not only by its splendid orchestration of color and camera but by the nerve of making such a boldly poetic, homoerotic film in that time and place.

Markopoulos eventually arrived in New York, where he became one of the leading proponents of the New American Cinema group and a fixture in the pages of Film Culture. By all accounts he cut a striking figure—elegant, witty, ambitious. He released his landmark Twice a Man in 1963, a stunningly photographed variation on the Hippolytus myth edited using the mosaicked style suggested by his influential essay, “Towards a New Narrative Film Form.” With The Illiac Passion (1964-1967), a florid reconstruction of Prometheus Bound, Markopoulos solidified his stated aim of “[enhancing] the survival of classical patterns and classical learning as a vital factor of our present-day culture” (“Twice a Man Statement,” 1965). He began experimenting with superimposition-rich films edited entirely in-camera—portraits of people (Galaxie) and places (his apartment in Ming Green, a church in Bliss). If Galaxie’s (1966) lineup reflected Markopoulos’ knack as a networker (Parker Tyler, Jasper Johns, Maurice Sendak, Susan Sontag), he left a more lasting impression on a younger generation of filmmakers: among them Warren Sonbert, Nathaniel Dorsky, Tom Chomont, Jerome Hiler, and especially his life partner, Robert Beavers.

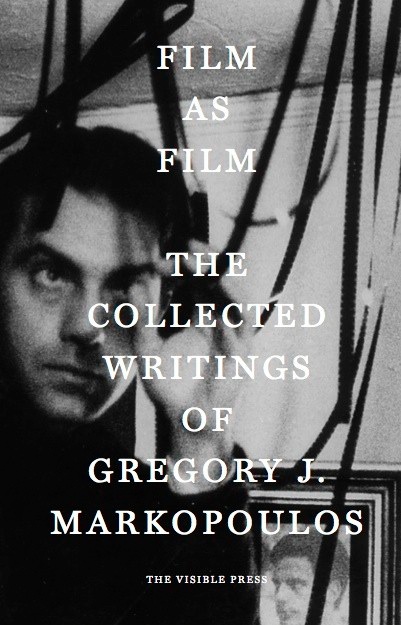

As a young man Beavers wrote Markopoulos asking “what a ‘Filmmaker’s education’ should consist of.” Markopoulos’ reply is one of the highlights of Film as Film: The Collected Writings of Gregory Markopoulos (The Visible Press), a recent anthology edited by London-based curator Mark Webber: “I sincerely believe that the filmmaker must become enamoured of the odour of celluloid, splicing cement, projection exhalations; he must feel the exhilaration through the pores of his skin,” Markopoulos said. “He must continue filming; he must continue working. He must never be obsessed with any formula save that always tentative formula which in time will become his style” (“Inherent Limitations,” 1966).

In the same talk, Markopoulos also broached the need for a decisive break from the main currents of the American avant-garde: “The filmmaker must anxiously seek a haven, not only separately from soulless and unimaginative society, but also independently from his fellow filmmakers; and more particularly from those artisans who would pervert celluloid beyond the human and reasonable which are its inherent qualities.” The hyperbolic note is characteristic. In the event, Markopoulos and Beavers left New York for Europe in 1967 and hardly looked back. Wounded by what he perceived as critical indifference and lax standards of presentation, Markopoulos withdrew his films from circulation and requested that P. Adams Sitney remove the chapter on his films from the second edition of Visionary Film (the chapter was restored in the 2000 edition). He put it plainly, “It is far better not to have any presentations as long as they are purposeless before the possibilities of the medium of film” (“Formal Account,” 1970).

This uncompromising attitude led him to conceive of an ideal cinema for an ideal spectator: the Temenos, an open-air sanctuary for “film as film”—an actual Arcadia given its location outside the small village of Lyssaria in Markopoulos’ ancestral Peloponnese. Beginning in 1980, Markopoulos and Beavers hosted annual screenings there for a small group of visitors and local villagers. During this same period, Markopoulos conceived of a sufficiently grand project to fulfill his epic mandate: Eniaios, an approximately eighty-hour work comprising twenty-two film orders that would literally incorporate his earlier American films. Owing scant resources and the enormous scale of the project, Markopoulos constructed the film without making prints. This task fell to Beavers after Markopoulos’ death in 1992; the surviving filmmaker has convened Temenos screenings for the first orders of Eniaios in 2004, 2008, and 2012.

Markopoulos’ leap of faith toward Eniaios and Temenos is the crux of Film as Film: The Writings of Gregory Markopoulos. Smartly arranged in five sections to emphasize different aspects of his life’s journey in film, the chronological shuffle nonetheless serves to highlight the underlying consistency in much of his thought. “There must only be a criticism of Enthusiasm,” he wrote of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1964) (“Innocent Revels,” 1964). “Any hostility which any spectator might have for technique evaporates before Beavers’ metaphysic, independent, pitiless and blessed critical protest which is the ecstasy of Plan of Brussels,” he opines four years later (“The Siege of Bruxelles,” 1968). And four years after that, envisioning his Temenos, he expands, “But who can begin the approach to the gates of the Temenos with its eloquent illumination in purple and gold; its shimmering surface; its golden triangle and glass screen? Let no one who is without awe enter for he will not be welcome” (“The Filmmaker’s Perception in Contemplation,” 1972).

In passages like these—and there are many in this anthology—Markopoulos’ ideal spectator begins to sound like an empty vessel. Once in Europe his unwavering conviction in the sanctity of the film poet’s vision is exclusively the province of himself, Beavers, and a very abstract idea of D.W. Griffith. His own sense of exaltation rests upon increasingly baroque denunciations: “A moment for the Cultural Zero. A moment for the failures, the bad people, the enemies at the helm of non-existent culture. A moment for the promoters and destroyers. A moment before the sinister elements of video. A moment before the performers of art tapes.”(“Erb and Tree,” 1975)

It seems that is not enough for Markopoulos to simply do the work. He must actually redeem the medium: “Today with a singular respect for the pornographic politicians that are strangling film, everyone discusses film and learns about films. So film as film systematically separated from the essentials, from the few elements that make up film itself, continues to be in a state of emergency; and, will continue to be in a state of emergency until the first stone is laid of the Temenos, the Intuition Space of two universal filmmakers named: Beavers, Markopoulos.” (“The Threshold of the Frame,” 1973)

I do not find insight in Markopoulos’ hammering away in this manner, though perhaps these later writings should be more charitably read as efforts to shore up confidence in his formidable endeavor. Indeed, at many points the essays read less as reflections than invocations (“Appear then munificent benefactor! Appear! I believe in your existence,” concludes the 1972 essay, “The Filmmaker’s Perception in Contemplation”). Ironically, it takes a text written by someone other than Markopoulos to evoke his magnetic appeal. In a journal documenting the youthful production of Swain (“From Fanshawe to Swain,” 1966), collaborator Robert J. Freeman, Jr. marvels at the young Markopoulos’ inspiration for color, camera, and location (“We had great fun with the architecture, he attacking with a stationary camera and seldom panning”) and his doggedness filming a bridge during a snowstorm (“[Gregory] would not leave tripod for wind”). “When in a few instances I have protested obscurity of purpose and inconsistency,” Freeman, Jr. muses, “he (dictator as he admits himself to be) claims some sort of divine guardian (his achievements support him strongly) in his inconsistent consistency.” Freeman, Jr. is frankly awed by Markopoulos and sounds a bit in love with him. The fact that Markopoulos would himself read this text ahead of a screening of Swain in 1966 is yet another example of the man’s remarkable chutzpah.

For all the ways in which Film as Film: The Collected Writings of Gregory Markopoulos is frustrating to read, the texts prove remarkably prescient on two fronts. First, Markopoulos’ limitless confidence in Robert Beavers has been amply repaid in the younger filmmaker’s oeuvre. The originality of Beavers’ style—at once intuitive and refined—bears the fruits of the safe haven Markopoulos proposed in his initial response to Beavers’ question about a filmmaker’s education in 1965.

More broadly, Markopoulos’ master concept of “film as film,” wielded both as mantra and protector throughout the book, makes a new kind of sense in the present situation, when the film experience is at once endangered and because of that the subject of renewed enthusiasm. He notes the critical importance of the projectionist as far back as 1968 [“…not so much an ordinary technician or worker as he will need to be not unlike a symphony conductor” (“Towards a Constructive Complex in Projection,” 1968)]. Similarly, Markopoulos’ concept of the true film spectator as a kind of pilgrim resonates with current interest in the spiritual qualities of cinephilia. Markopoulos’ passion for the cinema, his faith in the medium’s transformative potential, is beyond question. At some level he staked his life on it.

Mark Webber presents selections of Markopoulos’s films at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (April 1 and 2), REDCAT (April 6), the J. Paul Getty Museum (April 7), and the Los Angeles Filmforum (March 22 and April 12). A film series and conference on Markopoulos’s work takes place at Stadtkino Basel on April 23 and 24. ‘Film as Film: The Collected Writings of Gregory Markopoulos’ is published by The Visible Press.