An early memory from a cinephilic life: an ingenious transition staged by Buster Keaton and his collaborators for Seven Chances (1925). Buster gets in his car, but he makes no gesture, and the car does not move; rather, his automobile journey is depicted by the background setting simply dissolving into another place. At the same moment that I discovered this wonderful film for myself as a young teenager in the 1970s, I also read about it in a French Dictionary of Cinema held (by chance) by my local library in Melbourne. Claude-Jean Philippe (who still today, at age eighty, hosts special, weekly screenings at L’Arlequin cinema in Paris) described Keaton’s surrealistic yet perfectly clear and economical effect in this striking formulation: “Absolute speed is rendered by absolute stillness.”

The ingenuity of silent cinema, its speed and stillness: all this came back to me, in a flash, when I watched Miguel Gomes’s Tabu (2012). Early in the film, the present-day life of its characters in Lisbon seems bogged down in stasis: people sit or stand very still indeed. Then Gomes begins a scene between the melancholic Pilar (Teresa Madruga) and her troubled, older neighbor, Aurora (Laura Soveral), in a way that takes a few moments for the viewer to figure out, because he denies us the necessary establishing shot: the camera is fixed on one face, and then the other, but the background is glacially gliding by. This is, we realize, because we are in some kind of revolving restaurant. It is an odd, comedic touch characteristic of this director—but, like most details in Tabu, it takes us, by various routes, right to the heart of the film and its complex, inner life.

But Tabu does not inaugurate the telling of its narrative in the depressed present-day. Like an inversion of the strange, disorienting beginning of John Cassavetes’s Faces (1968), it starts—again, without immediately letting on that this is the case—with the viewing (by Pilar) of a film within the film. And what a weird, embedded film this is: poetic voice-over (read by Gomes), flowery piano score, and an agglomeration of adventure movie clichés. We see unfolded, conveyed in brusque ellipses, the tale of a white explorer in Africa, separated from the woman he loves; as his native assistants look on, he eventually surrenders himself to the waters where he will be swallowed by a crocodile—and hence able to live on, eternally, in this transmuted form. The punchline to this prologue tale is a glimpse of the woman whom the explorer left behind, placidly sitting by a crocodile: an impossible love.

All these settings, motifs, character-types and animals (especially crocodiles) will reappear, woven into the larger fabric of Tabu. But, for the moment in these introductory minutes, we are faced with a tricky question of tone: what kind of film is Gomes offering us here? Parody, pastiche, trash comedy? How serious, exactly, is he being? What we witness here draws upon an aggregate memory of every cornball, hopelessly imperialistic tropical adventure movie of the 1930s (of the kind that the original King Kong in 1933 was already wisely distancing itself from), crossed with the minimalistic, bargain-basement inventiveness of an Edgar G. Ulmer. But, also, not forgetting the surreal note of Romanticism (reminiscent of Peter Ibbetson, 1935) that is struck in that watery communion of untouchable woman and mute crocodile: even in the midst of the most baroque, tortuous conceptual games, and the most distanced, multi-layered movie allusions, Gomes likes to keep in play (if he can) a potential, old-fashioned tug on our heartstrings.

No one has described the intent of this prologue of Tabu better than the director himself: he told his cast and crew that he wanted to begin with the hangover of history—the worst, most obviously artificial residue of imperialistic fantasy. Then the challenge was, through the film, to retrace the steps of this condition—to take it back to the state of giddy drunkenness. And to do this, Tabu will need to relaunch itself, with another, more elaborate story.

Like in Jean-Luc Godard’s In Praise of Love (2001)—the same ironic or ambivalent title could have been used by Gomes—we encounter a narrative that proceeds backwards in time, in two large blocks. The modern story of Pilar, Aurora, and the latter’s African housemaid, Santa (Isabel Muñoz Cardoso) is, as a bold and unapologetic on-screen title proclaims, a Miltonian “Paradise Lost.” The old “masters” are losing their minds, the canny servants are taking whatever small, daily revenge they can; and, in-between these figures, ordinary people like Pilar and her moping artist suitor cope as they must with disappointments, frustrations and lost dreams. Already, the history of Portugal’s colonial past, not so distant, after all, in time, is stirring, lending a subterranean turbulence to these static figures locked in their apartments or glumly revolving in restaurants.

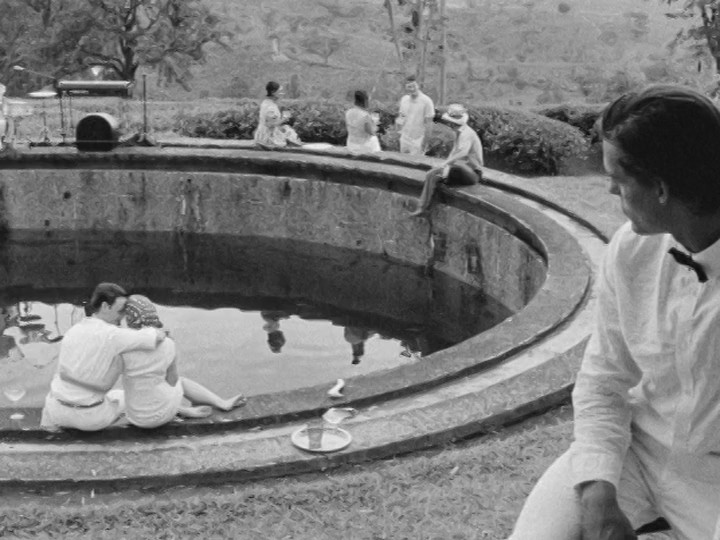

Once we plunge back into that past with Gomes, the stillness will be shattered and movement will finally be liberated. Two lovers—the young Aurora (Ana Moreira) and Gian-Luca (Carloto Cotta)—walk through the grass hand in hand, occasionally running or skipping a little. Nothing particularly spectacular in itself as action but, within the cinematographic, comparative context of times, places, and gestures so carefully established by the film, it signifies Paradise (the matching title of the film’s second part)—the giddy conquest of romance. Here is the drunkenness of which Gomes spoke (and which Marguerite Duras also conveyed, through completely different stylistic means, in her India Song of 1975). But it is a drunkenness mixed up with secrecy and the betrayal of a feckless spouse—Tabu here evoking both its namesake, F.W. Murnau’s 1931 South Seas collaboration with Robert Flaherty (which also used the Paradise/Lost titles), as well as a long history of nocturnal, doomed “lovers on the run” adventuress—and a political context that goes far beyond these intoxicated individuals who are almost completely oblivious to it.

It is scarcely four decades ago that Portugal relinquished its grip on parts of Africa. Many Portuguese filmmakers have tackled this history, most recently Pedro Costa, in the haunted elevator of “Sweet Exorcist” from the anthology Centro histórico (2012). Gomes relates in interviews how he came to approach this subject matter more indirectly, through his intuition of old, befuddled people living around him in the city, whose seemingly banal, tawdry problems and complaints came to evoke and echo the memory of another time and place—their experience of living through a period of colonial rule that they indelibly associated with youth and freedom, no matter what could be made, then as now, of the dire politics of the situation.

The way in which Tabu steps back in time, in stages, from the depressed present-day to the drunken past (but without the usual, dropped-in flashbacks) does a great job of conveying a process of remembering that is both individual and collective, romantic and political. The film is not (heaven forbid) a nostalgic apology in love’s name, like Baz Luhrmann’s garbled 3D transposition of The Great Gatsby (2013), for capitalist or colonialist excesses; but it does try to understand the uneven layering of personal and political experiences and knowledges across history, and in each, subjectively lived moment. Watching Tabu, becoming immersed in it over its almost two-hour stretch, reminded me of the metaphor used by Catherine Millet in her memoir Jealousy, the lesser-known and more anguished sequel to The Sexual Life of Catherine M., to describe the psychic work of unconscious recall: what is most disquieting when there’s an earthquake out at sea is not the obvious turbulence but, some time afterwards, the action and presence of the single, ancient stone, at last disturbed and dislodged, that floats to the surface. . . .

Tabu depicts and discusses various luxuries—of time, space and money—but it is, itself, pure arte povera. Despite the many reviews that describe it as “lush,” this extravagance is almost entirely an illusion, a tribute to Gomes’s ingenuity more than his budget. The director and his collaborators, such as his trusty sound man Vasco Pimentel (immortalized in the finale of Our Beloved Month of August, 2008, and scoring another cameo here as a lunatic aristocrat with a gun fetish), have testified to the hard fact that, when they arrived on location in Africa, the budget evaporated— leaving the “central committee” listed in the credits with the task of devising a new, radically reworked script day by day. Luckily, Gomes had already decided that the cinematographic “look” of this past story needed to be in 16 millimeter. Every subsequent decision, such as the treatment of the film’s second part as a dialogue-less “silent film” (but with voice-over and specific sound effects, creating the same ghostly, aural ambience as in Godard’s Le Petit Soldat, 1960), proceeded from these severe economic constraints. But rarely (since the days of Ulmer, in fact) has an ultra-low budget led to such necessary, richly expressive minimalism.

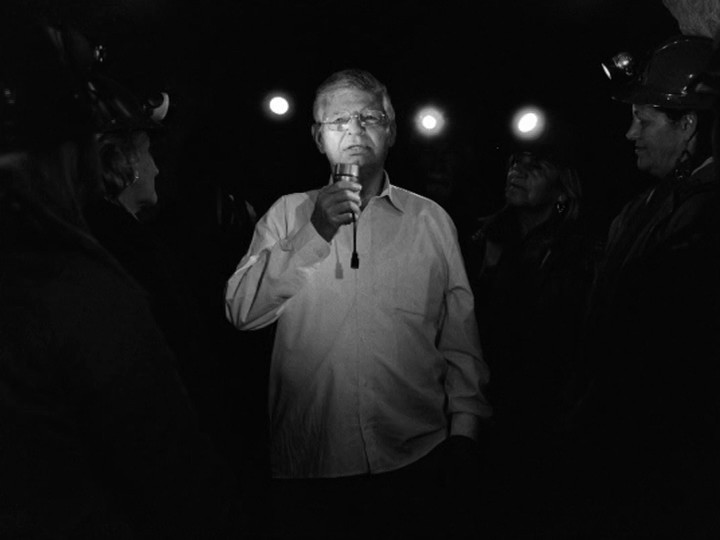

Gomes’s stringent art is an art of transitions. Often surprising and startling transitions, as when Beloved Month tips from seeming cinéma-vérité reportage into pure, melodramatic fiction; or when Tabu plunges from the present into the past, as the elderly, feeble Gian-Luca (Henrique Espírito Santo) begins to speak, opening a narrative parenthesis that, poignantly, will never be formally closed. In the original plan for Tabu, Gomes envisaged elaborate scenes devoted to the African citizens’s rebellious uprising against the Portuguese, in the same period that Portugal itself, back home, was undergoing its Carnation Revolution of 1974. But all this had to be scrapped when the money ran dry. What resulted was better: a single voice, like a distorted, tinny radio broadcast, in which an insurgent group claims responsibility for a murder it, in fact, had no involvement with. This is how history lurches forward, in the present, abruptly and violently; only in retrospect can the elaborations and veils of reminiscence give it the semblance of lushness.

I have not conveyed how funny, in and through everything else, Tabu is. Gomes’s deviation into conjuring the balmy life of a rock band led by Gian-Luca’s friend Mario (Manuel Mesquita)—history here tipping a little back into the retro 1960s, judging by the cover versions of pop hits performed/mimed by our merry colonial heroes—provides the film’s drollest, most camp moments. And then there is the beguiling mixture of fun and poetry when crocodiles eventually re-emerge into the story, post the prologue. A cute, baby crocodile in particular, that (as Gian-Luca tells us in voice-over) Aurora secretly gave a romantic name to commemorate their illicit love. And I will let you in on a related secret here, in which I have a personal investment. In the English subtitles, the name of this romantic croc is rendered as “Dandy.” This is absolutely and definitively incorrect. Long before filming began, Miguel Gomes informed me that, in homage to a certain Australian film critic who had championed Our Beloved Month of August (which is, indeed, one of the great films of its decade), this character would be called Dundee (which is clearly what you can hear on the soundtrack). You got it: Crocodile Dundee.