We expect documentary profiles of artists to tie the work into the life, encircling the subject even as he or she may remain an obscure object of desire. The formulaic interpolation of archival footage, assured voiceover, and a gallery of witty, glamorous confidantes all too often seems a one-size-fits-all approach, something exacerbated by the heavy demand for documentaries to fill the slates of film festivals and cable channels. It often seem that any artist worth his or her cult is in line for a close-up.

Gerhard Richter Painting and Patience (After Sebald) take a stealthier line, leaving aside biographical interest in search of a different kind of privileged view. One wouldn’t necessarily connect the two subjects, existing as they do in very different ecosystems of arts and letters, and yet there is undoubtedly strong overlap in their cultural patrimony (Richter was born in 1932 and has lived in Germany throughout his life while Sebald was born in 1941 and lived most of his adult life in England, but both were formed in what Sebald describes as the German “conspiracy of silence” following the second World War), aesthetic strategies (oblique evocations of historical trauma), and strong interest in photography as a medium for memory. Richter’s work has been lauded to a rare degree for a living artist, whereas Sebald’s renown gathered posthumously after his untimely death in an automobile accident in 2001.

As documentary subjects, then, the two men present very different challenges for the enterprising filmmaker looking to catch hold of the work without presuming too much of its author. The primary attraction of Corinna Belz’s film, as the title suggests, is the opportunity to watch the celebrated German artist at work. Richter has developed many different formal means of absenting himself from his paintings (gallerist Marian Goodman explains how her initial support of Richter’s work in 1980s New York was at least in part in reaction to the excesses of the neo-expressionists), and so there’s something doubly fascinating in observing the intensely physical means by which he achieves some of his signature blurring effects. Though Belz also includes Don’t Look Back-ish looks at the art world circus surrounding Richter’s public persona, the soul of the film are those extended sequences in which watch the artist simultaneously working on two large abstract paintings. A few gnomic utterances aside, his state of mind remains ever elusive even as the corporeality of the work comes into focus.

The intimate views Richter in his studio unfold in a much more leisurely, involved flow of time than the heavily edited scrapbook approach usually found in documentary profiles of artists, and yet it’s still worth wondering whether we’re any closer to an authentic picture of the artist at work. The issue becomes more pressing when Richter abruptly stops mixing blue paint with obvious exasperation. At first it seems that he’s encountered an aesthetic problem, but a few moments later he tells Belz that he doesn’t think he can proceed with the film. “Something is different,” he explains, indicating that he cannot access the deep intuitions necessary for painting when he knows he’s being observed. In a telling metaphor, he says that the camera’s glare is worse than being in hospital—a very different form of coming “under observation,” to be sure, but one no less debilitating for Richter.

Not least of Gerhard Richter Painting’s virtues: it shows that the artist may have a good deal of fun even when he’s working on an ostensibly solemn canvas—something to bear in mind when considering totemic art-historical readings of the paintings.

This exchange may complicate the film’s claims of privileged access, but it makes the documentary immeasurably more nuanced in terms of its contemplation of the complex mix of intuition and judgment that go into Richter’s art-making. Richter does continue to work in front of the camera, letting out a sigh of pleasure when he reveals an unexpected wave of yellow paint as he drags his squeegee across the canvas. Not least of Gerhard Richter Painting’s virtues: it shows that the artist may have a good deal of fun even when he’s working on an ostensibly solemn canvas—something to bear in mind when considering totemic art-historical readings of the paintings.

If Patience evokes a misty séance rather than a face-to-face encounter, that would seem in keeping with Sebald’s oneiric style, which, as many of the film’s speakers make clear, exhibits a strong affinity for the uncanny. The film sifts the author’s work through its close attention to place, specifically following after the English pastoral walk that structures The Rings of Saturn’s glinting narration. Gee’s previous documentary profile of Joy Division was similarly attuned to the way that art can come to be suffused with a place (Manchester in that case), though here the tempo slows to an easeful gait matching Sebald’s winding sentences.

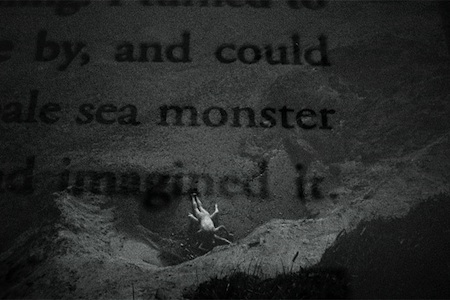

The film opens with images from Google Earth, contrary to the resolutely analogue atmosphere of Sebald’s books. One of the author’s devotees has taken the trouble to plot out Saturn’s itinerary, highlighting the book’s often curious landmarks on the computer aerial. Gee compliments this slightly gimmicky conceit with the view from the ground, appending grainy black-and-white film images of empty landscapes with citations for where the site occurs in the book.

It would seem from these beginnings that Gee is offering the audience a virtual pilgrimage to the significant sites of Sebald’s literary world, refreshingly free of the first-person intrusions that characterize many American documentaries. But several of Patience’s interviewees warn against the ready temptation to read his perambulating novels too literally. Robert MacFarlane, in particular, offers a humorous account of his failed attempt at “footstepping the footstepper,” which only resulted in disappointment when he finds sun instead of the requisite clouds, and happy idle thoughts instead of the expected world-weary contemplations of modern Europe’s catastrophes.

It’s to Gee’s credit that he allows these sentiments to complicate the film’s geographic impulse. The space he’s primarily concerned with, after all, is that of Sebald’s novels, and in this spirit he’s generous with readings of Sebald’s beautifully wrought sentences as well as several illuminating interpretations of the work. These seem to inspire Gee visually, as when he pairs Adam Phillips’ insightful definition of melancholy as being at an inexplicable loss, living in the aftermath of some unknown disaster, with aerial images showing the airplane’s insignificant shadow cast on the earth far below: a metaphorical association of image and idea more in line with the work of an experimental filmmaker like Jay Rosenblatt than a run-of-the-mill documentary profile.

Grant Gee does lean heavily upon British voices to address Sebald’s writing—it’s curious that no German speakers are represented—but his decision to leave these voices disembodied, only occasionally materializing as ghostly apparitions, gives Patience (After Sebald) a special pensive quality. No undue emphasis is placed on the more notable interviewees (Rick Moody, Tacita Dean); instead we have the sense of Sebald’s work being refracted through several different consciousnesses. Many of the speakers are pleasingly attentive to the way Sebald’s illustrated books rewards the materiality of reading, and it’s here that Gee’s film most fruitfully aligns with Belz’s. For if both films aren’t likely to convince those dubious of the reverential treatment accorded these artists, they nevertheless exhibit a genuine interest in the inner life of the art. So many documentary portraits seem anxious to validate their subject’s work and by extension the merit of the film itself. These two are more open-ended in their curiosity to see where the work will take them—a most inviting quality to find in a documentary.