Lenny Cooke may be Josh and Benny Safdie’s first foray into feature-length documentary filmmaking, but the brothers have a history of tinkering with verité-style realism. In The Ralph Handel Story (2006), an ersatz “behind the scenes” documentary following a terribly unfunny (and fictional) comedian, Benny Sadie took the stage of unsuspecting clubs with Andy Kaufman-esque disdain for the rules of the game. In There’s Nothing You Can Do (2008), he plays a belligerent commuter who screams at a crying baby’s mother, pressurizing the assembled citizens of the cross-town bus towards a reaction. In Solid Gold (2012) he’s yet another disappointment artist—this time a second-rate street performer who lures tourists into revealing themselves as they snap pictures and video. In Straight Hustle (2011), we watch two attempts at a street hustle in voyeuristic long takes, unsure how far the camera’s complicity extends.

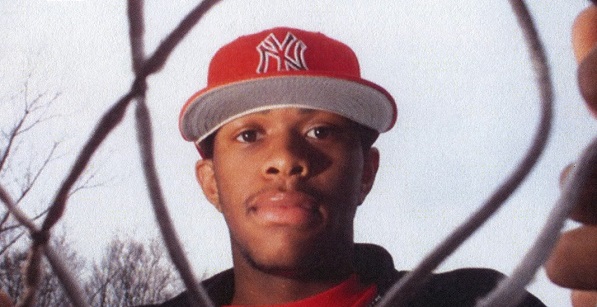

Even more than hot dog stands and camera phones, the Safdies seem to relish the vexing issue of character in documentary—the slippage between personality and performance betrayed by the word itself (character as the distinctive mark of one’s personality, character as the figure of fiction). Not unrelated, the Safdies betray a native New Yorker’s love of those outré figures who loosen the boundaries of everyday life—“a real character,” in the local parlance. With Lenny Cooke, a loose chronicle of a high school basketball star’s fall from grace, this interest in character takes a more distinctly reportorial form. The film dates back to 2001, when producer Adam Shopkorn began filming the teenage prodigy as he edged towards his fateful decision to forego college for a shot at the 2002 NBA draft. Years later, with Cooke’s star long since eclipsed by his former competitors LeBron James and Carmelo Anthony, Shopkorn persuaded the Safdies to revisit his old footage and see what could be made of the now thirty-year-old Cooke’s life in the shadows.

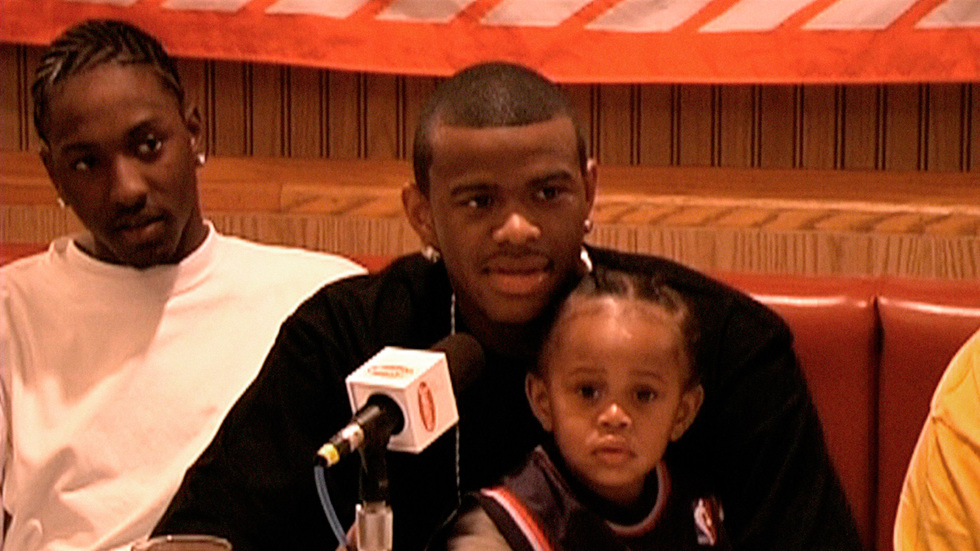

The resulting film is all prologue and epilogue, with the much-anticipated triumph all but marked “scene missing.” The stage is set for a comeback story, something Cooke himself seemed to expect when he showed up to his first meeting with Josh Safdie in a rented Jaguar. “The idea of him being this superstar,” Safdie told Susanna Locascio, “He had to drop that and start being real with us.” “Being real,” in this case, means crooning along to slow-jams at your thirtieth birthday: the Safdies’ interest lies in working the perimeter of behavioral detail rather than fleshing out a predetermined story arc. The first half of Lenny Cooke is essentially a found-footage film, but Benny Safdie’s editing sticks to the brothers’ habit of letting the camera run. Take a sequence of Cooke and several friends watching the 2001 draft on television: the fact that several prospects were plucked straight from high school obviously influences Cooke’s gamble, and yet the scene’s languid pacing as much attention to surface detail (a kid shaking more and more salt on his McDonald’s fries) as any putative foreshadowing. We’re left in the dark as to basic story information like how Cooke came to live with a white guardian in suburban New Jersey, but the Safdies have an undeniable knack for seizing upon footage that obliquely reveals the absurdity of Cooke’s situation: an argument in which he contends that you don’t need identification to board a plane, singing along to “Izzo (H.O.V.A.)” with a girl in his lap in Las Vegas, an encounter with a stranger in an airport who tells the 17-year old to “get that money.” They include just enough dead time of Shopkorn’s footage of Cooke touring an ESPN reporter around Bushwick for us to register the ridiculousness of a television personality in that sweater talking matter-of-factly with a Brooklyn kid about his plans to build a new YMCA once he makes his millions.

Throughout these early scenes, Cooke’s mindset remains inaccessible—not least to himself, one suspects. Though the causes of his failure remain somewhat obscure in the film’s telling, we infer that it had to do with a lack of character. The grown Cooke rails against his former handlers: “They made Lenny Cooke. I’m Leonard.” Which begs the question: who, then, is Lenny Cooke about? The specter haunting the documentary, as with its subject, is success. Watching the old footage, it’s hard to imagine that Shopkorn wasn’t as intoxicated with filming the next big thing as Cooke was with becoming it (in the event, any luster is provided by proximity to LeBron James). By lingering in the indolent pockets of anticipation and regret, the Safdies explore the recesses of the American dream. A feeble attempt at catharsis only comes courtesy of a CGI-aided sleight of hand. The adult Cooke steps into the past to lecture his younger self, acting as his own father figure; it seems that disillusionment doesn’t mean the end of illusions. A more bracing final word comes with Cooke’s off-the-cuff admission that his own son is a huge LeBron James fan: “It’s tough, isn’t it?”