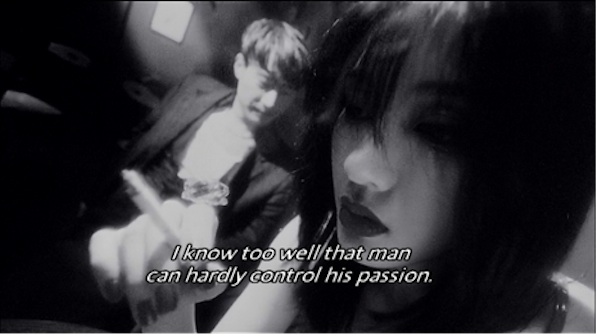

Every frame of Wong Kar-wai’s Fallen Angels is so saturated with flash, blur, hue and noise that the film feels like twice its runtime. By the time the end credits finally hit (after a mere 90 minutes), you’re so awash in visceral perception that you need a cigarette to accompany you in the afterglow. But let’s call it Wong Kar-wai and Christopher Doyle’s Fallen Angels, because cinematographer Doyle deserves above-the-title credit like few cameramen have ever earned. Just check out the first shot–caliginous black and white, the screen smeared with smoke and light, variegated planes of focus, the camera flush in the face of a gorgeous woman. Doyle executes a visual style that’s about as subtle as the gaudy bauble perched on Michele Reis’s slender digit.

The opener seems to be an optical feast, but it’s merely the appetizer, as Doyle serves up a nonstop banquet of curved and canted angles, step-print smears of action, estranged reflections, amoebic pools of color and light, and bulging wide-angle close-ups.

There’s an odd kinetic twitch embedded in the film. A sense of anticipation heightens the allure of every scene. Each shot in the present tense is merely a precursor to some ineffable future event which lies in wait just beyond the bend. The opening scene hints at a salacious plot worthy of the visual shindig—man, woman, passion, control. But with enough style, story comes to seem disposable, and any semblance of a plot soon dissolves amidst the barrage of neon, nylon, gun smoke, velocity and precipitation. Seriously, who needs a plot when you’ve got Doyle shooting Reis, the former Miss Hong Kong? This pair can transform a routine stroll through the subway into a salient event which will echo in your memory.

Film lovers fantasize that banal everyday existence might achieve transcendence, if shot and scored with enough exuberance. Wong and Doyle dive headlong into these delusions throughout the strange, audacious energy of the film’s first 30 minutes, an inspired display of creative genius by two veterans embracing the ragged, ambitious flair normally associated with amateur film endeavors. Eventually, the splendorous DIY aesthetics of Fallen Angels allow the viewer’s imagination to extend from envisioning self-as-subject to self-as-producer, as if great editing were merely a matter of quick cuts, and great cinematography merely a choice of odd camera angles, and great sound simply the staccato click of high heels on hard tile, backed by the instrumental tick and thrum of Robison Randriaharimalala’s über-smooth tune, “Because I’m Cool.” Sometimes great art dazzles us with the obvious brilliance and technical mastery of the creator (Rembrandt, Bach, Keats), but other times it tantalizes with its seeming simplicity (Klee, Schubert, Whitman), and makes believe that, with enough enthusiasm and diligence, it might have been achieved by any one of us.

As the inventive visuals accumulate in Fallen Angels, the characters are exposed as superficial constructs whose actions and behaviors are nearly impossible for the audience to identify with. A stoic hitman who effortlessly guns down dozens of armed thugs and (usually) emerges unscathed.

A stunning beauty who gets off in decrepit apartments by masturbating to a stranger’s garbage.

A flighty blond who dries her clothes with a light bulb and finds cause for celebration every time it rains.

A jovial delinquent who lost his voice after eating a can of expired pineapple.

At no point in the film is it possible to mistake these characters for real people. It’s worth remembering that Fallen Angels is essentially a supplementary film which Wong cobbled together from a discarded plotline from Chungking Express. It might even be argued that this is a film composed entirely of deleted scenes. At one point, Leon Lai’s hitman claims that he intentionally left certain items in his trash to provide his partner with clues about his personality, and the audience is often left to believe that they are sifting through Wong’s cinematic detritus, those aberrant snippets of character development which are typically sacrificed to the twin gods of continuity and pace.

While the vast majority of feature films rely on narrative and/or character to carry the audience’s attention from scene to scene, Wong and Doyle prefer to string us along with pure aesthetics. They celebrate style over substance, so it’s appropriate that the mise-en-scène is dominated by articles of camp and kitsch—vinyl shower curtains, cheap linoleum, flower-print umbrellas, latex dresses, obnoxious patterns, pastel walls, prosaic neon signs, corporate logos. Like human hermit crabs, the residents of Wong’s tawdry world seem content to scramble into someone else’s habitat without bothering to replace the furnishings or decorations.

Texture, image, surface, and appearance are consistently privileged over narrative or thematic function. The film doesn’t capture these hyperextended aesthetic surfaces so much as embody them. Fallen Angels is the cinematic equivalent of bell-bottoms or a paisley shirt. Just as such ostentatious displays of fashion inherently rely on their ephemeral status for their appeal, Fallen Angels feeds on its own transience, a diet entirely appropriate to Hong Kong in 1995. The relentless flash and fervor of the film cannot be sustained, and it eventually begins to feel feigned, affected, spent.

The audience finally must wonder whether there is a system hidden behind the everything-and-the-kitchen-sink aesthetics. At what scale does this cinematic static become a chant? Certainly, with such a glut of visual data, the film encourages and rewards close viewing with a slew of possible insights about life, crime, society, culture, Hong Kong. But these vague concepts pulse and flicker throughout the film, like the ubiquitous neon advertisements or the bullet trains which periodically puncture the night while the characters catch their breath. Like the film itself, any system of interpretation seems provisional rather than comprehensive, but the same could be said of real life. Film is still commonly considered the best available representation of our existence, and this self-referential conceit eventually emerges as another plausible theme.

Near the end of the film, the mute Takeshi Kaneshiro develops a sudden interest in home video, and his slapdash shots of his dad cooking and sleeping reinforce the notion that even the most mundane moments of our lives can acquire relevance if blessed with the artificial duration inherent to recording. Part of the attraction of Fallen Angels is that it simultaneously celebrates its own capacity for capturing life and its inherent inability to succeed in this endeavor. Upon consideration, the film’s berserk visuals fail to match the movement and distortion which mark our every glance, as our eyes incessantly pan across our lives and redistribute focus over myriad planes requesting our attention. Take a mental picture of your vision at any given moment, project it on a massive screen, and it would look artificially stylized. It is impossible to mimic the twinge of the eye, the replicated splay of shadow and luminescence, the dim reflection of the room in the computer screen, the ghost of your nose at the center of it all. We are so accustomed to distortion, agitation, and fluctuation that cinematic attempts to duplicate these elements seem derivative and highly stylized. Life will not be contained by celluloid, but Fallen Angels reminds us of the possible pleasures of continuing to set the trap.

Watch Fallen Angels on Facebook or Fandor.

Philip Maher has a Master’s Degree in Film Studies, which would be by far the most expensive decoration in his office if he actually had an office. His hobbies include pondering the semantic implications of Tsai Ming-liang’s use of indehiscent fruits as sexualized totems in The Wayward Cloud, analyzing the banausic heterodoxy of materialism as exemplified by the commodified appropriation of diegetic space in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s World on a Wire, and table tennis. He currently lives in South Korea.