The year is 1957, and Jordan Belson, James and John Whitney, Loreon and Dion Vigné—some of them leading lights of ’50s avant-gardes, others unremembered names from the same movements—are gathered at 1503 Golden Gate Avenue, San Francisco, California. The time is 10 p.m., and the tape recorder is on. Someone is talking about time, how what they like about animation is the idea that it “separates time, and you can work with it.” He goes on: “What I do is meditate on material and find what is meant to lead to what.”

Listening to that very personal remnant of a dinner party a very bizarre number of years later, experimental filmmaker David Sherman took that last statement as oracle. The way it’s presented in a video called To Re-edit the World, it’s unclear who’s talking. But present is abstract animator John Whitney, who created the “spiral of time” animation that would eventually become the key element of Saul Bass’s Vertigo title sequence. The psychedelic whirlpool graphic emerges from the pupil of an eye and spins out as a symbol of Jimmy Stewart’s fear of heights and loss of innocence as he backtracks through time to split hairs over Kim Novak in blonde and brunette configurations. This particular “spiral of time” is four decades old, but it’s David Sherman who’s been falling through it lately.

I’m not sure just how to explain this, but as he tells the story, the making of a video with the audiotapes and film reels of a stranger—his half-hour To Re-edit the World—was the reverse of the typical underground-film formula: a set of footage “found” him. It was 1997, and he was out looking for a place to hold his wedding to Rebecca Barten, but what they found was a Bay Area getaway unlike most. Its owner, Loreon Vigné, had built a temple to Isis, bred exotic large cats, and, some time back, made the acquaintance of Kenneth Anger, Anton LaVey, and Christopher MacLaine. “There was an amazing photograph of her with Christopher MacLaine holding this glass orb,” Sherman remembers. He’d worked for 12 years at Canyon Cinema, one of the United States’ primary distributors of underground and experimental films, and the significance of the photograph was not lost on him. They later learned Loreon Vigné was in possession of the film reels and audiotapes of her deceased beat filmmaker husband, Dion. Sherman would eventually receive the reels and have a three-year honeymoon with them before putting together a piece that doesn’t so much sum up Dion Vigné in the well-worn biographical format as reinhabit him.

It was 1997, and he was out looking for a place to hold his wedding to Rebecca Barten, but what they found was a getaway unlike most. Its owner, Loreon Vigné, had built a temple to Isis, bred exotic large cats, and, some time back, made the acquaintance of Kenneth Anger, Anton LaVey, and Christopher MacLaine.

To Re-edit the World tumbles through time like an otherworld version of Contact‘s opening sequence. Vigné, Sherman says, was a heroin addict from the early ’50s on and came to San Francisco to start a new life (that attempt ended when he died of an overdose in 1970). Sherman’s video joins him in the “new life” period. It opens with some context, sound-biting history through flashes of TV-anchor types and some key-wording by Allen Ginsberg about the best minds of his generation. But like an archivist on LSD, Sherman builds up hilarious visual sequences that feel the moment. Codes on the edges of film stock, the triangles, circles, and squares, blow up to big type that even old occultists can read. A Scotch tape case’s plaid motif becomes the button-up world of Hitchcock’s late-’50s San Francisco, and the view on a Sunset brand tape case springs to life as moving clouds in a stormy sky that might be landscape for another of Hitchcock’s horrors.

The material has an intimacy only handmade audio and handheld 16mm can supply. The reedited life passes through the Fillmore: Ornette Coleman and Artie Shepp in 1966, Bobby Beausoleil’s Orkustra in 1967. (Sixteen days after that performance, Beausoleil would meet Anger at a free-love free-for-all at Glide Memorial Church at which the words “you are Lucifer!” would be spoken.) The video rolls through more of Hitchcock’s San Francisco. (Remarkably, Vigné was filming the city streets in the same year that they were being filmed for Vertigo, and Sherman forms the shots into a Hitchcock homage.) The images uncover a sweet low-key San Leandro lawn party, where LaVey, Anger, and a bearded lady pick at the hors d’oeuvres table and frolic with jungle cats. (It’s a scene Sherman has reimagined with great, corny music and Anger irony.) The video loses itself in Vigné’s psychedelic period, as abstraction and light-play mingle with jazz before visiting the landmarks of Vigné’s San Francisco as they disappear. Notably, the home of the Church of Satan is shown in various states of decay after Vigné himself has passed away, until the “black stain in a pink-and-gold neighborhood” vanishes completely.

That last image, the final one of the film, is a nod to all the movements that got co-opted and dissolved. But the dissolution is not only a metaphor. “You have these amazing tools now,” Sherman says about the video technology that let him reimagine Vigné’s world in such detail, “but there’s an incredible fragility to them. That I could find this film and be able to play it now on my machines, it’s not going to happen anymore. Just to have a stable format for 80 years in 16mm allowed for a certain retention.” If there are larger questions in all this, questions about legacies and art and lifestyles and resistance, Sherman hopes they will be asked.

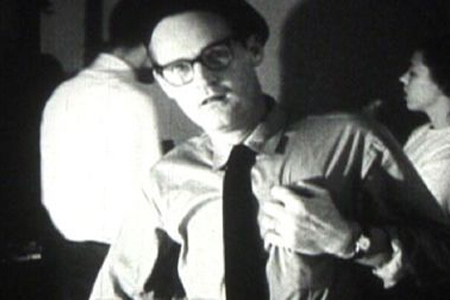

For the cover of his piece, he chose one image to represent the attention that should be paid to these kinds of disappearances. It comes from a party where everyone’s swigging from a bottle marked “Death.” A man heads toward the camera, tilting his head and clutching his chest pocket. The reeditor freezes the frame. The spiral of time stops spinning. The man, Christopher MacLaine, seems to be experiencing a moment of perplexed happiness, an in-joke. The glow would be brief: a bad speed habit later turned that man into a San Francisco recluse, hiding his body and talent in a small room whose only entrance was the window.

Someone just opened the curtain and let in the light.

This article appeared originally in the San Francisco Bay Guardian in 2002. Former San Franciscan David Sherman now lives in Bisbee, Arizona.