Few filmmakers have a series of successes that resembles that of Matt Porterfield. From his debut, Hamilton, to Putty Hill to the opening-in-theaters-this-week I Used to Be Darker to the in-the-works Sollers Point (the proverbial “end” to a loosely-formed trilogy started by the first two), the trajectory of Porterfield’s career thus far hardly seems plausible. Yet it isn’t unimaginable. It is absolutely, entirely real. In part, it’s because Porterfield has surrounded himself with an assortment of folks as exceptionally competent as he is: Jordan Mintzer (producer of three of the films), Steve Holmgren (two of the three), Ryan Zacarias (the latest) and a number of other folks mentioned below. Filmmaking is a team effort. The better the team (generally), the better the work.

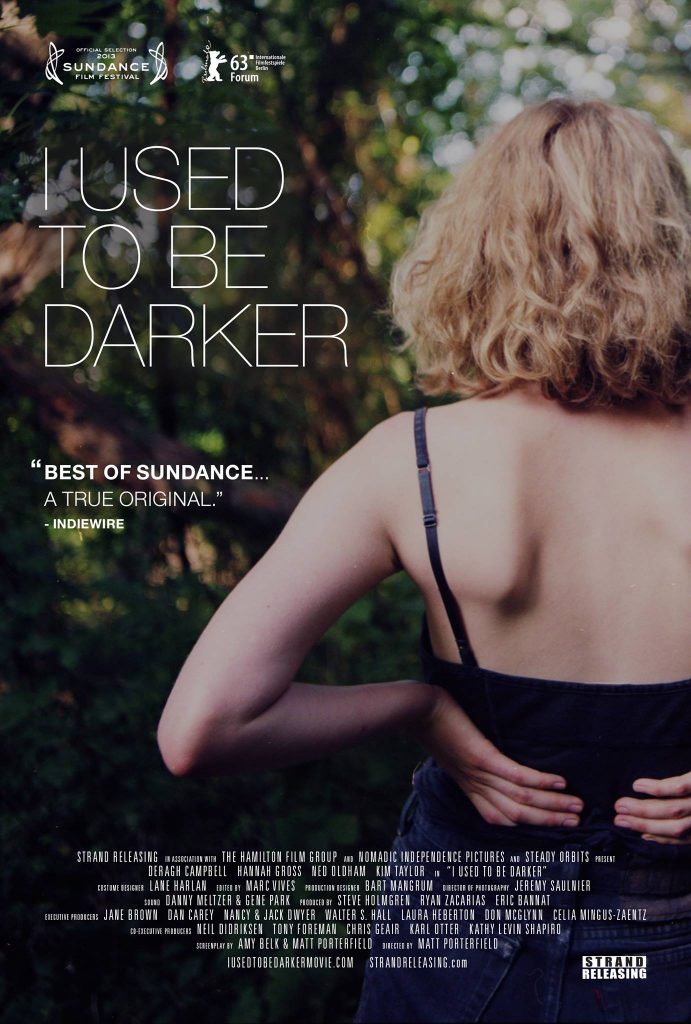

Thanks to a pact with Cinema Guild, the initial installments of the trilogy are available here. For Darker, Strand picked it up after its Sundance premiere. Run (don’t walk) to the nearest cinema to see it.

I spoke with Matt Porterfield at Independent Film Week in New York.

Jonathan Marlow: Let’s start at the beginning. Hamilton. That isn’t really the beginning.

Matt Porterfield: That’s one beginning. The beginning of the beginning.

Marlow: It’s the beginning as far as we’re concerned for this conversation.

Porterfield: The beginning is probably dropping out of film school and using the money that my grandparents had saved for my last years of college to try to make a feature. Long gestating. It took a year to write. This was 2001 and we shot in 2002. I decided to edit it myself and that took four years. It wasn’t ready for festival submission until 2005 and we premiered at the Wisconsin Film Festival in 2006. We shot and printed on 16mm in a weird aspect ratio, 1.87:1, which was made up. Jeremy [Saulnier] wanted to shoot widescreen but, of course, it’s 16mm.

Marlow: It’s an approximation of the old Academy ratio?

Porterfield: Exactly. We went and took the ground-glass out of the camera, etched new lines and then, when we printed and exhibited, we added a matte.

Marlow: That’s crazy. But pretty smart.

Porterfield: It worked out. It made exhibition easy once the projectionist knew there was a matte.

Marlow: Did you ever blow it up to 35mm or did you leave it at 16mm?

Porterfield: We only screened it on 16mm and then DVCAM once.

Marlow: When we met in Berlin briefly, just for a handful of seconds prior to a screening of Putty Hill. . . . Let me present this notion a little differently. I was on my way to a meeting at the Berlinale and I ran into Scott Foundas. Scott said, ‘I’m off to see this film by a great filmmaker. He made one of my favorite American independent films of the last decade.’ Perhaps I am embellishing a little.

Porterfield: Sounds good.

Marlow: He was praising Hamilton. He tells me, ‘This film is playing. If you have a chance, you should see it.’ I immediately decided to postpone my meeting and go see Putty Hill. Who [and what] could deserve such praise?

Porterfield: That’s high praise.

Marlow: Putty Hill was a film made under duress, in a sense. You wanted to make a different film and yet you made Putty Hill instead.

Porterfield: Yes.

Marlow: It must be a mixed blessing. On one level, you premier your first film at a relatively small festival. Then you can’t get your second film made. You make another film, which is very loosely constructed (narratively-speaking) and you get to premiere it at the Berlin Film Festival. That is a bizarre trajectory.

Porterfield: It was a big leap in many ways.

Marlow: I should say so!

Porterfield: I am happy that my producers and the cast had the courage to switch gears and just give this scenario that came together in two months for Putty Hill a whirl. We’re sitting here at IFP for Independent Film Week and it was with the help of IFP that we made the film. They awarded the screenplay that I was trying to produce, Metal Gods, a grant in the form of a camera package from Panasonic in 2008. It was that package that enabled us to make Putty Hill. ‘We have this gift. Let’s not let it go to waste. We have nothing to lose. We have a bunch of people we want to see on film. Some locations. Let’s see if we can put something together.’ We did it in twelve days. It was crazy.

Marlow: As a director, you’re working without a net, in a sense. You’re putting a lot of faith in the cast to realize what you’re trying to achieve. It is also essential to be a good director.

Porterfield: Coming up with a strong framework and then trusting your collaborators. The essential relationship is a director’s relationship with his or her cast. That experience—the experience of making Putty Hill—made me realize that I could put a lot of trust in the actors. If I cast well, they trust me, I trust them. We can build something together. At least in the case of Putty Hill and I Used to Be Darker, a lot of the decisions were born of ideas from the actors. Allowing that collaboration to breathe and come to fruition is, I think, the most important role of a director who wants to work with actors.

Marlow: Would you say planning those two films and Sollers Point, which is the project that you have here at Independent Film Week, form a loose trilogy related to place?

Porterfield: Yes.

Marlow: But it seems as if each of those films, even if they form a loose conceptual trilogy, are very different in their construction and in the way that they are conceived. We cannot speak of the third one because you haven’t started making it yet but we can imagine it as you have envisioned it. To what extent does Darker bridge Putty Hill to Sollers Point, in the sense that it is something very different from your first two films?

Porterfield: To answer your earlier question, Putty Hill was born from conversations I was having with real people.

Marlow: In the script that you intended for your second film, will you ever go back to it?

Porterfield: Metal Gods? I hope to. I’d love to make it. It’s an ambitious project with a big ensemble cast of teenagers. So it’s a challenge.

Marlow: Absolutely.

Porterfield: Darker came more from an idea born from my imagination and expanded through the process of writing with my co‑writer, Amy Belk. Both of us had been married and divorced so it became essential to try to tell a story, a balanced story, about the experience of divorce. We cast while we were still writing. The actors, particularly Ned Oldham and Kim Taylor—who are musicians in real life, playing musicians in the film—brought a lot of their life experience as well as their original music to the page (and then to the film) when we translated it for the screen.

I would say that the collaborative experience of making Putty Hill gave me the courage to work collaboratively with the cast of I Used to Be Darker, even though there was a one-hundred-and-ten page script we were trying to realize. In the case of Putty Hill, it was just a five-page scenario. Moving forward, I’d like to continue in that vein. If I could ever finance a longer treatment, I’d like to do that. I’d like to enter production without having to think about how many script pages we need to make a day, which was the more traditional experience of making Darker. That’s hard. In some ways, taking the scenario—in prose form, contains no dialogue and is maybe five to twelve pages—and expanding it to the screenplay does force me to work through the gaps and flesh out everything. The characters, particularly. I think it’s still really freeing to work from just a scenario, just a treatment. I hope to do that again. I hope with Sollers Point, to a certain extent, we can throw out the screenplay on the way to production and work from a different kind of model.

Marlow: But you have a certain comfort in working either way?

Porterfield: Yes.

Marlow: You have a feeling after these experiences that working with a framework rather than a script is preferred?

Porterfield: I’m not sure that I have a preference. I think you have to be able to do both. I want to be able to do both.

Marlow: You think that Sollers Point would definitely benefit from that approach?

Porterfield: I think so. In order to finance the film I have to finish a decent screen play, a feature length script. I’m halfway through a second draft and feeling good about that, although I was loath beginning the process. Now that I’m writing a screen play I think what I have is better than the treatment was. It contains all the same information, but it contains more. I think when you enter production, though, you have to figure out how to create a production model that allows you to remain flexible and move freely within the sort of confines of trying to make a certain number of script pages each day. When you get stuck on page numbers and scenes and you can’t through things out or don’t have the time or the space in your schedule to do things that come up in the moment that are far better than what you spent months or years writing, if you can’t do that then I feel like ‘what’s the point?’ It’s not exciting. There’s no life, no magic or breath. I go back to that word, because I feel like you want the space to let life breath into the scenario that is inspired by life that’s intended for the screen.

Marlow: Would you say that Hamilton would’ve benefited from that process?

Porterfield: Yes. We were pretty rigid. Whenever we threw things out, it felt like a huge loss (at least during production). It made it hard for me to edit the film because I had written the screenplay, I directed the screenplay and then I was trying to edit what we actually had. But it didn’t fit with the original screenplay. I learned from that experience. A lot of things we threw out and the things that we found along the way when we were making Hamilton, I think, are better than what I’d written. But, at the time, I didn’t see that. It always felt like a big sacrifice or a loss was happening when we had to throw a scene out or lose dialogue for some reason. It’s not. It’s almost always. . .it can be a blessing. A surprise.

Marlow: What was your film experience prior to Hamilton? Were you making short films?

Porterfield: I tried to make shorts when I was in school. I did a couple years at NYU. My most ambitious short was about a utopian group home in Bushwick. It had a great cast. A lot of people that I was hanging out with at that time. This was 1998. But I lost the sound reels. All of them. I have the 16mm dailies and a VHS transfer. I’ve never done anything with it.

Marlow: That’s a shame.

Porterfield: That was my unfinished short. That’s it. I took so much time off between leaving NYU and getting back into Hamilton, I didn’t really do any film-related stuff in between.

Marlow: You needed to then dive into making a feature? What made you do that? What made you think you could get away with that?

Porterfield: Stupidity, I think. Naïveté. Just being hungry to transition out of my life in New York and make something. I hadn’t made anything in four years. I didn’t have an artistic practice. I decided, ‘I’m going to dedicate myself to this ambitious project and I’m going to learn something from it. If I get a film out of it then that’s a bonus.’ If the film’s good, that’s a miracle.

Marlow: There you go. What was your working process like with Amy on Darker?

Porterfield: Amazing. We were together at the time. We were in a relationship and living together. We wrote every word together. A lot of that happened at home and then we’d go out to a café or we’d take walks. Play a round of ping pong. It was something that we were doing daily so we developed a kind of shorthand. I went on to direct and, in some ways, that makes the visuals my own. But the voices in the script—the characters—we share those. It was really exciting to collaborate in that way. To write dialogue with someone else. To work through scenes with someone else. I’ve always had strong collaborations with my producer, Jordan Mintzer, who I’ll always send a draft. He’ll give me detailed notes and I’ll send the next draft. I do the same thing when I’m editing. I send him a cut and he gives me notes. That’s shaping the story. But this was really writing every word. It was great.

Marlow: Are aspects of the aftermath of that detrimental to a relationship?

Porterfield: Yes. I think that they were.

Marlow: It was like ten years packed into a relatively short period of time?

Porterfield: [Laughs.] Yes. It’s emotional. There’s a way in which you’re just like, as partners and collaborators, if you’re doing it all, it’s like you’re overexposed. There are couples that can make it work. I think we did make it work. We made a film that we’re both really proud of, but the aftermath is, I think, the only way forward is to continue in different directions. But she’s writing screenplays and fiction. She comes from a fiction background.

Marlow: Amy and I discussed her new project at the Creative Capital retreat. It seems quite remarkable.

Porterfield: I’m excited to see it.

Marlow: For Sollers Point, you’re writing the script right now. That will allow you to raise a certain amount of money. You’re going to probably raise more money for it than, I suppose, for Hamilton and Putty Hill combined. You have casting aspirations that are far beyond those two films….

Porterfield: That’s right.

Marlow: Besides the location, in what way do you see them as connected? Obviously, you’re making them all. This idea of a self‑described trilogy prematurely colors the new project prior to even beginning it. I don’t know whether that’s a positive thing or a negative thing. Or a mixture of the two. It may be a necessary evil in trying to get funders interested. ‘Look, this is the completion of a larger project.’

Porterfield: I feel more the latter. Honestly, it is my producers that like to talk about it as a trilogy.

Marlow: That is what I suspected.

Porterfield: I don’t care. [Laughs.] It’s not my idea. I am interested in the idea of making a film that is structured more like a triptych. Not a three-act structure. Kind of like Joe [Apichatpong] Weerasethakul makes these bifurcated narratives, to divide something in [parts].

Marlow: I know what you mean.

Porterfield: It might be interesting. The idea of a triptych. . . . Sollers Point is going to take place in a milieu that is more similar to Hamilton and Putty Hill. Darker is a little bit more petit bourgeois but that is still a part of the middle class. I feel that if I have an agenda as a filmmaker it is to make films that tell stories that reflect the diversity of the American middle class. They are part of a whole. Sollers Point, in many ways, we’ll see how it feels when we’re going into production but I hope that it doesn’t change. It feels like one that is personal.

Marlow: Aspects of an autobiography in the way that the treatment is constructed? What do you see in these films that are most personal?

Porterfield: I think in Putty Hill, I Used to Be Darker and now Sollers Point, there is always a character—usually one character and, in the case of I Used to Be Darker, two—that I deeply identify with. [A character] that brings me into the story. That I kind of imagine as my alter-ego. I realized this after making Putty Hill. I have to have some autobiographical element. In Putty Hill, it’s the dead kid. Putty Hill is a meditation on loss but it is imaging how others would reflect on my memory if I died.

Marlow: I hadn’t thought about it like that.

Porterfield: It was written after a period of extremely self‑destructive behavior. Despair. Substance abuse. I am the missing protagonist in Putty Hill. In Darker, I’m connecting with Kim Taylor and Hanna Gross who plays Abby, the daughter. I’m writing about my experience when my parents were divorced and I was Abby’s age and away at my first year of college along with my own experience of divorce. I’m much more connected to Kim’s experience than Nick’s, autobiographically. Then, in this case, it’s like a study of isolation, a young man who is my age. I’m 36. He’s 33. But pushing back against limitations, many self‑imposed and some a condition of his socioeconomic reality. His character is different than mine. The more precise autobiographical element is the fact that he lives with his father. I live with my father.

Marlow: You live with your father presently?

Porterfield: Yes. When I’m in Baltimore. I commute. And I’ve lived with him in the past.

Marlow: That is a great thing, I think.

Porterfield: In this one, there are dream sequences for the first time. I feel like the whole thing is coming from a subconscious space. More so, certainly, than Hamilton but also more than Putty Hill and Darker. That’s why I think it’s my most personal.

Marlow: I know that you’re disappearing for Ontario tomorrow. You’re screening Darker there. We don’t need to talk about why that is but it’s a great reason. Probably the best reason. I’ll leave it at that. With film festivals, there’s a family. There is this camaraderie that creates a support structure to encourage work. It encourages people to continue. Sundance, for all of its faults, can truly encourage filmmakers to continue working. For some folks. For others, it discourages them and makes them never want to make films again. If you can rise above that and make what you consider to be personal films and still have them embraced by audience and critics and distributors, having someone commit enough to something that you take very personally and say, ‘I love this and want to distribute it’…. Not everyone has that luxury.

Porterfield: No. I feel very privileged. I get frustrated with the business. With the commerce of it. But I want to support myself and want the films to reach wider audiences while still making work that is uncompromising. There is a difference between collaboration with compromise versus compromising just for the bottom line (even though you always have to think about these issues when you’re trying to realize a project).

Marlow: Does the process with Darker actually make it easier to get funding? Do you feel—with Strand distributing it and giving it a national release and the fact that it premiered at Sundance. . . .

Porterfield: I’m hoping that we get good press and the release times well with where we are in terms of development of Sollers Point. But I think the most valuable thing about having made Darker is that it shows anybody that I know how to work with actors. If nothing else, I’m proud to show that film, along with Putty Hill, to any potential cast and say, ‘This is what I’m doing. I think it would be exciting to work together.’