The run-up to the official stateside release of The Grandmaster on August 23 has been long and, you might say, comprehensive. In July, Matthew Weiner hosted A Salute to Wong Kar-wai at the Academy and, as you’ll see below, while Wong was in Los Angeles, David Poland took the opportunity to interview him as well. Currently, there are ongoing retrospectives at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York (through August 24) and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (through August 25), and in Nashville, the Belcourt is presenting a series of Wong Kar-Wednesdays (through August 21).

The MoMI retro is the occasion for a series of new essays at Reverse Shot, beginning with Michael Koresky on the “grimily splendid 1994 film Chungking Express. Considered the quintessential Wong film until In the Mood for Love sidled into our lives six years later, Chungking Express would seem to be a film with its own expiration date, just like the cans of Del Monte pineapples and sardines that become its strange obscure objects of desire. Yet even though Chungking’s moment (the now hazy cinematic nineties, when it genuinely seemed like everyone wanted to see something that was a little out of the ordinary) has come and gone, there still is nothing quite like this vibrant portrait of one pocket of Hong Kong three years before the entire region was subsumed into China. Its vitality in 2013 is a testament to the nonaggressive inventiveness that marks all of Wong’s cinema.”

Matthew Weiner’s interview at the Academy

For Matt Connolly, Happy Together (1997) “continues to be that rare beast: a queer film by a celebrity art-house auteur who has not staked his or her reputation on the chronicling of LGBT experience…. Do the queer romances at the film’s center become one-to-one matches for their straight counterparts elsewhere in Wong’s oeuvre, or does this brief encounter between recognizable directorial vision and atypical topic tweak the inner workings of Wong’s style? The answer, perhaps unsurprisingly, seems to be a little of both.”

“An exhilarating rush of speed, motion, and blurred light, Wong Kar-wai’s 1995 reverie Fallen Angels is basically 96 minutes of the best trailer you’ve ever seen,” writes Jim Ridley in the Nashville Scene. Jordan Cronk in Reverse Shot: “Our ‘heroes’—a hit man and his lovelorn partner; a mute, ethically dubious ex-con; a scorned lover; and a blonde femme fatale—such as they are, all seek escape, yet seem to reside in the shadows as a step toward the light would require a courage they have yet to fully muster. These tumultuous emotional coordinates, charted via Wong’s achingly beautiful montage, render Fallen Angels the most existential of action flicks, a fluorescent fever dream of kinetic energies and inarticulate amour fou.”

“In 2008, Wong Kar-wai followed the disappointment of My Blueberry Nights by returning to one of his earlier films, 1994’s spottily available Ashes of Time,” writes Chris Wisniewski. “And though it may not differ as markedly from the original as Coppola’s Apocalypse Now Redux did, [Ashes of Time Redux] nevertheless remains an unqualified triumph, the kind of cinematic experience that reminds audiences why they fell in love with Wong in the first place, whether they’re rediscovering the film or seeing it for the first time.”

David Poland also spoke with Wong in July

Aliza Ma goes back to 1990, to Days of Being Wild, which “both anticipates Hong Kong’s handover from British rule to mainland China in 1997, and evokes the past, specifically the 1960s; Days thus bears feelings of both longing nostalgia and reckless exuberance, personal displacement and political tumult. With a formal rigor and aesthetic inventiveness that has since defined the electrifying arrival of the Hong Kong Second Wave cinema, Days marks the beginning of Wong’s unique dialogue with history, and lays bare his most essential and personal motivations for filmmaking.”

Sam Ho revisits Wong’s debut feature, As Tears Go By (1988), “an art film nudging to break through a genre picture; a simple story with a hodgepodge of stylistic flourishes; a violent triad film as well as a tender love story, featuring a kissing scene cherished by fans of Hong Kong cinema as one of the most romantic in Chinese film history.”

Reverse Shot may or may not get around to In the Mood for Love (2000), so let me recommend Criterion‘s collection of essays and videos. Then, of course, there’s 2046 (2004), which the New York Times‘ Manohla Dargis has called “an unqualified triumph.” And My Blueberry Nights (2007), which provoked Slant‘s Ed Gonzalez to write, “My man Wong Kar-Wai’s style is ossifying faster and more depressingly than my gal Joan Crawford‘s mug did back in the day.”

Which brings us to The Grandmaster. Since its premiere in Berlin in February, there are, reportedly, at least three versions floating around: the original, a European cut, and Harvey Weinstein’s version for the U.S. release. “By Wong’s own recounting,” writes Nick Pinkerton at Moving Image Source, “130 minutes became 125 for Berlin which became 108 for the States—and this from a purported four-hour rough cut!” The reception in Berlin leaned negative, but going by my Twitter feed, I can tell that The Grandmaster is going to have its champions in the States.

Nick Pinkerton is one of them. “A cottage industry of Ip Man entertainments have sprung up while Wong did his kung fu [a reference to over ten years of preparation], including Wilson Yip’s protean 2008 Ip Man and 2010’s Ip Man 2, both starring Donnie Yen, and Herman Yau’s 2010 The Legend Is Born: Ip Man and Ip Man: The Final Fight, released this spring. The particular care taken on The Grandmaster is evident from [its] first fight.” And while he notes that the film’s been a hit in mainland China, that’s “not to say that Wong’s film is not, in its way, still very out-of-step with the state apparatus.”

A recommended read. Critics Round Up, in the meantime, has been collecting relatively recent reviews from, among others, Michael Sicinski and Mike D’Angelo.

More Wong? Catherine Grant‘s got you covered. She’s posted two big, big roundups of scholarship at Film Studies for Free, one in December 2008 and the other in May 2011.

Update, 8/12: Kenji Fujishima announces that In Review Online will be revisiting Wong’s films, “one by one, day by day, up until the U.S. release of The Grandmaster next Friday.”

Updates, 8/14: Peter Labuza at IRO on As Tears Go By: “What we find here, more than in any of Wong’s other works, is a cultural meshing of styles, an auteurist finding small moments to mark a personal stamp in a film otherwise slavishly tied to its genre.”

Calum Marsh in the L on The Grandmaster: “Wong renders the film’s half-dozen wuxia set pieces as lavish, almost painterly displays, spectacles of such inspired decadence that it’s a treat just to luxuriate in their beauty.” The Grandmaster is “a decidedly ‘artisanal’ wuxia, a genre film with high-art aspirations crafted with a near-peerless eye.”

Updates, 8/16: Kristi Mitsuda in Reverse Shot on 2046: “Like Before Sunset, this continuation of characters from an earlier film, in this case In the Mood for Love, rejuvenates and deepens the possibilities of the oft-scorned term ‘sequel,’ which typically indicates nothing more than a passionless cashing-in on an established brand, worlds away from the glorious expansions proved possible by Linklater and Wong.”

“The Grandmaster is another of director Wong Kar-Wai’s examinations of time as the great tragic human leveler and humbler,” writes Chuck Bowen in Slant, where Jake Mulligan interviews the filmmaker. “This is a film that’s more likely to invite comparisons to the writings of Marcel Proust than the previous Ip Man films featuring Donnie Yen as the icon.”

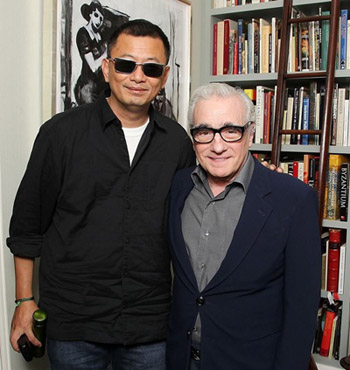

“Martin Scorsese will lend his name to director Wong Kar-wai’s kung-fu epic The Grandmaster by adding ‘Martin Scorsese Presents’ to its title,” reports the New York Post.

Updates, 8/18: Nicolas Rapold interviews Wong for the New York Times.

Sean Gilman calls Days of Being Wild “one of the great films about the post-war generation and the lingering effects the war had on their psyches, their visions of the world.” More from Daniel Gorman at IRO on Wong’s “first collaboration with cinematographer Christopher Doyle in arguably one of the most important director/photographer partnerships in modern cinema history; his first brush with building a stock company of performers (Maggie Cheung, Andy Lau and Jacky Cheung all appeared in Wong’s debut feature, As Tears Go By (1988), and, with the exception of Lau, they, Leslie Cheung, Carina Lau and Tony Leung would appear in future Wong projects); and, perhaps most importantly, his first film to deal with his most personal obsession: the mercurial, abstract, fleeting quality of time itself.”

Also at IRO: Kathie Smith on Ashes of Time, “an existential melodrama of unmoored warriors, torn from their code of ethics by their own personal agony of unrequited love… The crucial difference between this and Wong’s other films lies in its setting: in the grandeur of the wide expanses and endless horizon lines that are absent in the dominant urban settings elsewhere in his body of work. In this case, the emotional landscape finds a perfect match with the barren and mysterious physical landscape of the desert where the fallen heroes find themselves temporarily trapped or lost.”

Francisco Lo on Chungking Express: “In getting back to basics while strolling through his childhood neighborhood of Tsim Sha Tsui, Wong would make a film that established a style that would come to define his brand of cinematic poetry for the better part of the ’90s.”

John Oursler: The “ephemerality of human interaction… is the thematic center of Fallen Angels, and it’s manifested through an exhausting visual bombardment.”

Kenji Fujishima: “I decided to see if the intervening years had possibly improved my response to Happy Together (1997), the one Wong film that had always left me indifferent. Lo and behold: On this, my third viewing of the film, I suddenly found myself drawn in more intensely to the film’s human dramas and the melancholy, homesick vision underneath.”

Update, 8/19: For Roderick Heath, writing at Ferdy on Films, “as the melancholic warriors of Ashes of Time and the oddball spin on the loner-assassin motif in Fallen Angels portended, The Grandmaster proves rather a dizzying sprawl of images and almost associative storytelling methods that revise how this, or indeed any, kind of filmmaking can deliver. It may be Wong’s most stylistically and thematically ambitious work.”

Updates, 8/20: “The Grandmaster has gone over much better in China… than in Europe and North America,” notes Michael Smith:

While Wong has typically been a darling of western critics and cinephiles—especially in the period lasting from Days of Being Wild in 1990 to In the Mood for Love in 2000—his movies have often been quizzically regarded as arty and pretentious specialty items back home. I think the reversal evidenced by The Grandmaster’s reception can be explained by what might be termed its China-centric qualities, especially the way Wong explores notions of Chinese identity and history and, perhaps most importantly, the philosophical side of kung fu (though it is also chock-full of good old-fashioned kick-ass fight scenes that should satisfy genre aficionados). Western critics have been quick to criticize the new film’s narrative “patchwork” quality (it is certainly the most elliptical thing Wong has ever made) and they definitely have a point. To paraphrase something Andre Bazin said about Robert Bresson, however, I would argue that Wong sees in his narrative awkwardness the price he must pay for something more important; for, while it may not be as “perfect” as beloved earlier films like Chungking Express or In the Mood for Love, I believe The Grandmaster’s astonishing thematic richness makes it more profound than either.

The staff at the Playlist presents its complete retrospective.

Viewing (7’43”). From Kevin B. Lee, here in Keyframe: “Every Fight in Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, Ranked.”

“If you’ve only seen the American Cut of The Grandmaster, you haven’t seen The Grandmaster,” argues David Ehrlich at Film.com.

Updates, 8/21: The Grandmaster “isn’t the most gracefully shaped of his films, more an off-balance gourd than a symmetrical vase,” writes Stephanie Zacharek in the Voice. “But an imperfect Wong Kar-wai movie is still a Wong Kar-wai movie.”

“Ashes of Time and The Grandmaster open up as works clearly at home within their maker’s canon,” writes Jake Cole at Film.com, “and, in some ways, the most vivid, if not necessarily the best, displays of his style. The director’s romantic regret and yearning get their most active depictions, not merely in the generic terms of their respective wuxia boundaries but in the literal actions of movement and gesture that communicate through a punch as much as is said in a desirous glance.”

Back at IRO, Kathie Smith: “Sharing aspects with Days of Being Wild (1990)—some would say to the point of being an indirect sequel—In the Mood for Love is adorned with an elegiac mise-en-scène, Hong Kong and its émigrés re-imagined via locations in Bangkok, spawned by Wong’s childhood experience of relocating to the colony from Shanghai in the 1960s. If this vision of the city can be said to idealize the past, it also acts as a mirror to the film’s glamorized melodrama of abstained passion: Both have a perfect existence, but only under the spell of memory.”

The Hand, Wong’s short included in the 2004 omnibus film Eros, “stands a flawlessly constructed, near-perfect gem,” argues Daniel Gorman. And: “Outside the shadow of In the Mood for Love,” writes Carson Lund, “2046 reveals itself as one of Wong’s pinnacle achievements.”

New interviews with Wong: Nigel M. Smith (Indiewire) and Hillary Weston (BlackBook).

Updates, 8/23: Film.com‘s collected fan art from all over, “tributes to their favorite Wong films (which overwhelmingly appear to be Chungking Express and In the Mood for Love and its sequel.”

“When Ip Man slyly asks ‘What’s your style?’ it’s clear that Mr. Wong is asking the same question because here, as in his other films, style isn’t reducible to ravishing surfaces; it’s an expression of meaning,” writes Manohla Dargis in the NYT. More on The Grandmaster from Steven Boone (RogerEbert.com, 3/4), A.A. Dowd (AV Club, B-), Glenn Kenny (MSN Movies, 4.5/5), Andrew O’Hehir (Salon), and Keith Phipps (Dissolve).

Drew Taylor interviews Wong for the Playlist.

Updates, 8/24: Eric Hynes, who wrote about In the Mood for Love when Reverse Shot surveyed the best films of the first decade of the new century, interviews Wong for Moving Image Source.

Vulture‘s Bilge Ebiri gets Wong talking about three key scenes in The Grandmaster. More reviews: Steve Erickson for Gay City News and Kenji Fujishima at IRO, where Alex Engquist calls My Blueberry Nights “a feature-length simulacrum disguised as a creative departure, a film in which every element is both so familiar and so unmistakably out of place that the entire experience is near-surreal…. This is a film without a country or even much of a universe to call its own, drifting amid vague intimations of Americana and memories of far better movies.”

Updates, 8/29: “The Grandmaster is an opera in which the arias are delivered in kicks, flips and close strikes,” writes Jim Ridley in the Nashville Scene. “It has the exhilarating athleticism that makes people lifelong fans of martial-arts movies, but the fights bring us inside the characters’ heads—the performers spar with the liquid quickness of thought, belief and passion expressed through action. Despite its grounding in the hidebound biopic genre, it’s unmistakably its maker’s movie—a historical pageant splintered by time and loss into gorgeous, madly romantic fragments, each bearing the intense pang of its passage into memory.”

And Ray Pride talks with Wong for Newcity Film.

Updates, 8/30: Ben Sachs in the Chicago Reader: “It wasn’t until I watched The Grandmaster for a third time that I was able to make sense of the plot—on the first two viewings, I struggled just to find my bearings. This may be because the movie flirts with being a history lesson and an unrequited love story, but doesn’t really follow through with either. It’s full of red herrings, so to speak, leading the viewer to expect something epic when it’s really focused on the internal desires of a few people. While I find this narrative structure fascinating in theory, I’m not sure if Wong pulls it off. Maybe it’s because he didn’t shoot the movie according to any organizing design that none of the scenes, barring the martial arts fights, feels more significant than any other. Everything is sumptuous and suggestive, minor and major details alike. When I finally figured out what was going on, I found much of the stylization superfluous.”

“The movie’s combination of action and historical drama is frequently awkward, and the story, which covers nearly 20 years of Ip’s life, is disjointed and choppy,” finds Josh Bell in the Las Vegas Weekly. “The Grandmaster feels incomplete. It’s a series of lovely moments that never quite come together into a movie.”

Update, 9/3: Writing about Chungking Express, In the Mood for Love, and 2046 for Film International, Shashank Saurav notes that Wong “started his career as a graphic designer. As a graphic designer he adored the still photography of Robert Frank and Henri Cartier-Bresson, who was also the main inspiration behind Satyajit Ray’s work, and the sleek fashion work of Richard Avedon. Martin Scorsese and the American and European new waves were a huge influence, but it was fellow director Patrick Tam who perhaps made the greatest practical difference; Wong Kar-wai wrote Tam’s Final Victory (1987) and in return, Tam nurtured Wong Kar-wai’s directing aspirations, even supervising the editing on Days of Being Wild three years later. Interestingly, Wong Kar-wai claims that his non-linear shooting style came, not from film, but from a novel called The Buenos Aires Affair, by the Argentinian novelist Manuel Puig.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.