“About halfway through Alfonso Cuarón’s astonishing Gravity,” begins Variety‘s Justin Chang, “Sandra Bullock, playing a lost astronaut stranded 375 miles above Earth, seeks refuge in an abandoned spacecraft and curls into a floating fetal position, savoring a brief respite from her harrowing journey. Of the many sights to behold in this white-knuckle space odyssey, a work of great narrative simplicity and visual complexity, it’s this image that speaks most eloquently to Cuarón’s gifts as a filmmaker: He’s the rare virtuoso capable of steering us through vividly imagined worlds and into deep recesses of human feeling. Suspending viewers alongside Bullock for a taut, transporting 91 minutes (with George Clooney in a sly supporting turn), the director’s long-overdue follow-up to Children of Men is at once a nervy experiment in blockbuster minimalism and a film of robust movie-movie thrills, restoring a sense of wonder, terror and possibility to the bigscreen.”

Todd McCarthy in the Hollywood Reporter: “‘Houston, I have a bad feeling about this mission,’ George Clooney’s veteran astronaut Matt Kowalski half-jokes at the outset from his perch in orbit around Earth, which looms massively beneath. It’s a sentiment few viewers will agree with once their jaws begin dropping at Cuarón’s astonishing 13-minute opening shot, which gyrates and swoops and loops and turns in concert with the movements of the space shuttle and those of Matt, who jets around untethered while mission scientist Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) tries to fix a technical problem outside the ship. It’s as if Max Ophüls were let loose in outer space, so elegant is the visual continuity, making for a film that will have buffs and casual fans alike gaping and wondering, ‘How did they do that?’ and returning for multiple viewings just to imbibe the sheer virtuosity of it all.”

“Gravity is very much an action adventure, one very occasionally more meditative than most, but it’s unashamed of its desire to thrill you,” writes Oliver Lyttelton at the Playlist. “And thrill you it certainly does: it’s visceral, knuckle-chewingly tense stuff, Cuarón and his co-writer and son Jonas expertly packing obstacle packed on top of obstacle in the way of the astronauts’ return home, without losing touch of humanity or humor. The camera floats as weightlessly as its subjects, but the shots (often extended, but always in a way that favors storytelling above showboating) are always clear, and more often than not composed with meaning and artistry—courtesy again of the great Emmanuel Lubezki. And with the director being careful to ensure the void of space doesn’t carry any noise, the excellent score by Steven Price (Attack the Block, The World’s End) helps to keep things both breathless and beautiful.”

“And while it might be easy to dismiss aspects of the film as special effects heavy,” adds Screen‘s Mark Adams, “it is to Clooney and Bullock’s credit that they breathe real life into characters who could well be subsumed by the technology, jargon, space suits and danger that surrounds them…. Bullock’s combination of intelligence and straight-forward charm works perfectly here.”

Screening Out of Competition, Gravity‘s opened the 70th Venice Film Festival and will screen as a Special Presentation in Toronto.

Updates: “On a superficial level,” writes David Jenkins at Little White Lies, “this is your regular, down-home disaster movie in which we join a trio of plucky, bantering astronauts during a routine space walk which goes very south very quickly. Their trio swiftly becomes a twosome and the remainder of the film comprises a catalogue of micro-second clutches and grabs for a lifeline of any sort. Yet—and some may find this side of the film a mite on-the-nose—Gravity operates as a bold (possibly even eccentric) and majestically rendered parable on the wonders of creation, with a very specific focus on the details of reproduction. Imagery of umbilical chords, foetal positions, wombs and characters triumphantly surfacing from the amniotic river sit surprisingly comfortably against a visual backdrop of decaying space stations and an infinite shroud of nothingness.”

Gravity is “a brilliantly tense and involving account of two stricken astronauts,” writes the Guardian‘s Xan Brooks, “a howl in the wilderness that sucks the breath from your lungs…. It comes blowing in from the ether like some weightless black nightmare, hanging planet Earth at crazy angles behind the action. Like Tarkovsky‘s Solaris (later remade by Clooney and director Steven Soderbergh), the film thrums with an ongoing existential dread. And yet, tellingly, Cuaron’s film contains a top-note of compassion that strays at times towards outright sentimentality.”

“What’s astonishing to realize is that, whenever the actors are floating in space and not filmed in the interior of various pods, shuttles and space stations, the only thing that’s real is their faces,” writes Matt Mueller at Thompson on Hollywood. “Every other element, from spacesuits to helmets to crumbling shuttles, debris and bodily fluids (a tear springs loose when Stone decides all is lost), was created using digital effects. Besides being the single best advertisement for 3D since Avatar, Gravity‘s images are so pristinely realized, and Cuaron’s long, lingering shots allow for phenomenal sequences of astronauts bashing into metal, parachute silk and one another, that the experience, while often unsettling and frightening, becomes pure cinematic nirvana.”

Guy Lodge at In Contention: “Effortlessly sympathetic and resolute even when cocooned to the point of invisibility in a spacesuit, Sandra Bullock puts her impressively restrained performance to the fore just when the film needs her to, without straying from the character’s slightly dour vulnerability or succumbing to focus-pulling bravado; it’s a role that at once requires a movie star, and requires her not to be one. Some may feel disconcerted or even disappointed that Gravity shifts from a mode of cool (even avant-garde) observational spectacle to a more human-focused survival story—you might even choose to see it as a bloodless final-girl horror movie.”

Cuarón is “a cinematic astronaut whose Mission Control is his retinue of visual enablers, led by Special Effects wizard Tim Webber,” writes Time‘s Richard Corliss. “As the director told Entertainment Weekly’s Jess Cagle, ‘Each single bit of film is a different technology.’ … We should mourn the demise of a glorious century or more, when ‘film’ meant the passage of celluloid or acetate, at 24 frames per second, through the sprockets of a projector. Now it’s almost all on disc, not pictures but pixels. But what Avatar achieved—and Rise of the Planet of the Apes and Life of Pi and now Gravity, each outdoing its predecessor in the filmmaker’s eternal quest to astonish us—represents a triumph of digital technology and human artistry. Cuarón shows things that cannot be but, miraculously, are, in the fearful, beautiful reality of the space world above our world. If the film past is dead, Gravity shows us the glory of cinema’s future.”

“Comparisons to Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Ang Lee’s Life of Pi are inevitable and well-earned, but in fact, Gravity operates as a companion piece to Cuarón’s last film, Children of Men,” writes the Telegraph‘s Robbie Collin. “In that film, humanity had suddenly lost the ability to reproduce, and the result was global meltdown. But here, Cuarón is telling a different but related story of terror and mortality and hope. With nothingness pressing in on all sides, in a place where the grip of someone else’s hand is all that keeps you from the void, life really does seem like a miracle.”

Updates, 8/29: “The one problem with Gravity is that the plotting never quite matches its visual imagination,” finds Geoffrey Macnab, writing in the Independent. “There isn’t the same urgency or plausibility here found in JC Chandor’s recent, similarly themed All Is Lost (which featured Robert Redford as a lone sailor whose boat is sinking.) At times, as the astronauts desperately battle fire, tangled parachute strings and malfunctioning machinery, matters risk becoming just a little banal and predictable. Even so, this is a film that, at its best, really does induce a sense of wonder.”

“Much of the film is so transporting that it’s a letdown when a handful of corny Hollywoodisms start popping up during the second half,” finds Jon Frosch, writing for the Atlantic.

For the Los Angeles Times, Nicole Sperling talks with Cuarón and Webber about inventing a wide range of special effects.

Glenn Kenny is “not a little disturbed by the mewlings of various and sundry folks who travel the digital spaceways, claiming that the movie, co-written and directed by Alfonso Cuarón, is somehow an ignoble enterprise in that it does not acknowledge the Ray Bradbury short story ‘Kaleidoscope’ as its story source.” And he sets out to prove, eloquently and convincingly, that this is not the case.

Updates, 9/1: The Voice‘s Stephanie Zacharek now counts Cuarón “as one of our greatest living directors… No space movie arises from a vacuum, and the obvious comparative pulse points for this one include The Right Stuff and Brian De Palma’s sorely underloved Mission to Mars. The Right Stuff isn’t so much about space as about the space program, but Cuarón… captures the mingling of duty and curiosity that motivates any human being who actually makes it into space. And Cuarón, just as De Palma was, is alive to the empty-full spectacle of space and to the workaday poetry of the words astronauts use to describe it.”

A “sweaty-palm suspense movie which is also a spiritual odyssey and an audio-visual-tactile exploration of space travel, it delivers a conventional three-act structure and character arc with such conviction and panache as to make old-fashioned storytelling seem more daring than [Jonathan] Glazer’s obfuscation,” finds David Cairns. “Quite the most remarkable major studio release I’ve seen in a long time.”

“Jonas Cuarón’s script Desierto was such an inspiration to his father, Alfonso, for its stripped-down narrative and immersive character experience that the older man asked his son to collaborate with him on another project with the same features.” That, of course, would be Gravity, and, as Nicole Sperling reports for the Los Angeles Times, the younger Cuarón will begin shooting Desierto in Spanish with Gael Garcia Bernal in October. Desierto “explores the story of illegal immigrants who cross the border into the United States and end up running for their lives from an American who has taken border patrol into his own hands. While they fight for their lives, the two immigrants fall for each other.”

Viewing (3’30”). For the Guardian, Josh Strauss talks with Cuarón, Bullock, and Clooney.

Update, 9/2: “Cuarón, always one eager to tinker with film form, here has taken on the role of an Imagineer-like visionary, crafting a cinematic rollercoaster that’s both visceral and dreamlike in its capacity pull viewers into a queasy encounter with the realistic perils of space,” writes Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn. Gravity is “a brilliant portrait of technology gone wrong that uses it just right.”

Updates, 9/3: “Comparisons to this year’s Robert Redford survival drama, All Is Lost, have been long in the making and entirely fair,” writes William Goss at Film.com, “though I was myself called back to the surprisingly life-affirming tenor of The Grey (my #1 of last year). The fact that Cuarón’s film strives to be something more than thoroughly harrowing—no small feat in and of itself—solidifies its existence as a marvel of not just technical craft but sheer imagination as well.”

“This isn’t just the best-looking film of the year, it’s one of the most awe-inspiring achievements in the history of special-effects cinema,” declares Tom Huddleston in Time Out London. “So it’s a shame that—as is so often the case with groundbreaking effects movies—the emotional content can’t quite match up to the visual.”

Updates, 9/4: Writing for Cinema Scope, Alexandra Zawia suggests that “whatever [Cuarón] achieves here visually is never really matched by a profound narrative.”

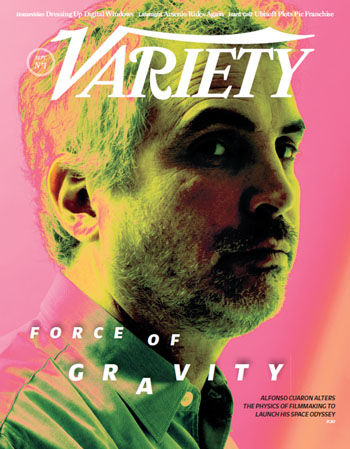

In Contention‘s Kristopher Tapley notes that in Variety‘s cover story on Cuarón, none other than James Cameron says: “I was stunned, absolutely floored. I think it’s the best space photography ever done, I think it’s the best space film ever done, and it’s the movie I’ve been hungry to see for an awful long time.”

Updates, 9/7: “Never before has a movie set in space made the dangers so viscerally plain,” writes Paul Marks for the New Scientist. “As you may expect from the title, physics has a lead role, and the screenwriters have done a fantastic job of demonstrating it—from the way tethered astronauts bounce off each other to the orbital mechanics of space debris—with impressive accuracy…. Gravity‘s storyline wins great credence from the factual space-flight asides that root the fiction in reality. For instance, it is mentioned that if you can drive a Russian Soyuz capsule you can probably also take the helm of a Chinese Shenzhou. This is correct: Shenzhou is indeed derived from a Soyuz design. And the Kessler effect—in which a piece of hypersonic space debris smashes into a spacecraft, starting a chain reaction that generates still more debris—is well shown, too.”

Brooks Barnes profiles Bullock for the NYT: ” To film one sequence, Ms. Bullock had to stay perfectly still and in character while a camera rushed toward her at 25 miles per hour, stopping only about an inch from her face. Other scenes required her to be strung up horizontally by 12 wires while puppeteers, including some who worked on War Horse on Broadway, maneuvered her through choreographed movements. ‘I got into it and didn’t last 20 seconds,’ Mr. Cuarón said.”

Updates, 9/8: “Gravity turns out to be a movie so visually unprecedented that no verbal description can begin to do it justice,” writes Mike D’Angelo at the Dissolve. “This is the film Cuarón, with his penchant for moving the camera freely through every axis, was born to make…. Cuarón still likes to show off—one shot that travels into Bullock’s helmet, briefly assumes her point of view, then drifts back out again, all without a cut, serves no real purpose except to impress—but his free-floating, untethered approach has never been better justified. At the same time, Gravity respects physics, turning Bullock and Clooney’s efforts to save themselves into a series of improvised real-time calculations. In short, it’s one hell of a ride.”

“Cueing the viewer with a heavy-handed score, Cuarón rarely slows the proceedings down long enough to generate lengthy suspense,” argues Ben Kenigsberg at the AV Club. “The movie presents its characters with one challenge after another, but doesn’t take a breath to give the audience its bearings. Apollo 13 presented a more richly detailed space-rescue operation; the screenplay kept viewers acutely aware of, say, the condensation on electrical panels or which switches need to be pushed at a given time. Watching Gravity often feels like watching an especially long prep reel for Star Tours, without ever being allowed to board the ride.”

“Gravity is a tale of survival,” writes EW‘s Owen Gleiberman, “and its suspense emerges from an implicit pact that Cuarón, through the awesome verisimilitude of his staging, makes with the audience: The movie is basically telling us that it won’t cheat, that the way the characters are going to get out of this, if they do, will be something that we can believe. The ebb and flow of Gravity‘s story is deeply organic—it seems to be making itself up as it goes along, and that’s how it hooks us.”

“People may hail it as a new cinema, a brave new way of merging spectacle and intelligence, a paradigmatic shift on the order of Kubrick’s 2001 mixed with the Lumiére‘s L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat,” writes Jason Gorber at Twitch. “Yet no words can truly express the experience of Gravity.”

Updates, 9/11: “Whatever misguided impulse led Alfonso Cuarón to make the baby in Children of Men‘s intense birth scene completely CGI—in an otherwise impressive if flawed film—is driven by the very same sensibility that has given us the whole of Gravity,” finds Adam Cook in the Notebook. “Cuarón believes too fervently in artificiality’s power to deceive, and the result is a film so hypocritical that it crashes back down to Earth far sooner than its climax.”

Nick McCarthy, writing at the House Next Door, is another to emphasize the “vast space between the quality of its virtuoso technique and its trite screenplay…. The gut-wrenching, immersive elements in Gravity are almost above reproach, but ultimately, the experience of watching Ryan grab for objects in space is more compelling than her grasping for significance in her life. It’s all effect and little affect.”

“Cuarón’s camera may seem weightless,” writes A.A. Dowd at the AV Club, “but his clunky dialogue weighs Gravity down.”

Update, 9/12: “Like a great amusement park ride you’ve just been on with your friends, I (and many other people) wanted to get right back in line and do it all over again,” writes Bob Turnbull. “I just needed a few extra minutes for my muscles to relax and my toes to get back to normal.”

Update, 9/21: David Poland interviews Cuarón:

Updates, 9/27: Dan P. Lee profiles Cuarón for New York.

Stephen Marche, writing for Esquire, suggests that Gravity is “the first truly 3D movie” and that it “may be the densest visual experience ever made.”

Which, more or less, is why Marche likes it. And why Calum Marsh, writing for the L, does not: “Despite constant intimations of philosophical import and cosmic grandeur, Gravity ultimately resembles nothing more than an unusually portentous Disney theme-park ride or a video-game cutscene expanded to feature length, Cuarón having marshalled his talents toward what’s essentially the world’s most expensive 90-minute sizzle reel. It’s effective only insubstantially and superficially.”

Updates, 10/5: “Stripped down, lean, and taut, Cuarón’s film may be either the most expensive avant-garde movie ever made or the most approachable, mass-appeal experimental work of art—like WALL-E‘s ‘define gravity’ dance writ on the scale of Erich von Stroheim,” writes Eric Henderson at Slant. “If seeing Earth from above for the first time left astronauts like Glenn feeling like they’d just been born again, Gravity‘s simple muscularity restores wonder to cinematic representations of outer space and reinstates the integrity of blockbuster filmmaking.”

Buzz Aldrin—yes, that Buzz Aldrin—for the Hollywood Reporter: “We’re in a very precarious position of losing all the advancements we’ve made in space that we did 40 years ago, 50 years ago. From my perspective, this movie couldn’t have come at a better time to really stimulate the public. I was very, very impressed with it.”

More from Sam Adams (Philadelphia City Paper), Jason Bailey (Flavorwire), Josef Braun, Richard Brody (New Yorker), Jake Cole (Film.com), Paul Constant (Stranger), Richard Corliss (Time), Glenn Heath Jr. (San Diego City Beat), Robert Koehler (arts•meme), Patrick Z. McGavin, Wesley Morris (Grantland), Adam Nayman (Cinema Scope), Andrew O’Hehir (Salon), Ray Pride (Newcity Film), Ben Sachs (Chicago Reader), Marc Savlov (Austin Chronicle), A.O. Scott (NYT), Matt Zoller Seitz (RogerEbert.com), Dana Stevens (Slate), Kelly Vance (East Bay Express), and Andrew Welch (In Review Online).

Updates, 10/13: “Gravity is something now quite rare,” writes J. Hoberman for the New York Review of Books, “a truly popular big-budget Hollywood movie with a rich aesthetic pay-off. Genuinely experimental, blatantly predicated on the formal possibilities of film, Gravity is a movie in a tradition that includes