“Tsai Ming-liang is one of the few uncontestable giants of what was once quaintly called ‘art house’ cinema still working at peak power,” begins Nick Pinkerton, writing for the L. The occasion is the retrospective opening tomorrow at the Museum of the Moving Image and running through April 26. Also tomorrow, a new restoration of Tsai’s debut feature, Rebels of the Neon God (1992), sees its first theatrical release in the US at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Once that week-long run is up, it screens again at MoMI on Saturday, April 17.

Back to Nick Pinkerton: “Tsai seems to suspect that he’s outlived the art house, perhaps even cinema itself. Prior to the release of his most recent film, 2013’s ravishingly bleak Stray Dogs, Tsai suggested that he may be leaving behind traditional cinematic exhibition entirely, finding museums and galleries more hospitable to starkly non-commercial work of the sort in which he deals. (His 2009 Face was partially financed by the Louvre, and entirely shot on the museum’s grounds.) Well before The Death of Cinema became a 21st century buzzword, Tsai was uniquely attuned to the changes facing the medium at the beginning of the new millennium, an interest expressed in his Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003), which takes place in a waterlogged Taipei cinema at the eve of its permanent closure, during a screening of King Hu’s kung-fu classic Dragon Inn (1967).”

The New Yorker’s Richard Brody notes that MoMI’s series opens with Vive l’Amour (1994), “a wryly comic drama about a romantic triangle as well as the story of a luxurious and empty Taipei apartment where a suicidal salesman of cremation urns (Lee Kang-Sheng) lives as a squatter. When a real-estate agent (Yang Kuei-Mei) brings her lover (Chen Chao-Jung), a street vender, there, Tsai stages the trio’s erotic comings and goings with an incremental screwball precision, as if Jacques Tati had given free rein to his sexual fantasies. But the filmmaker grounds the irony in quietly flamboyant melodramatic moods, as in a scene where the agent waits alone in bed with an operatic pout that calls to mind grand Technicolor tearjerkers. The center of Tsai’s singular universe is the slight, angular, puckish Lee, who stars in all of Tsai’s features and lends them the soulful yearnings of silent-comedy luminaries as well as an uninhibited carnality, both homosexual and heterosexual.”

The other day, I noted that Paul Felten has a piece on Tsai in the new Brooklyn Rail, and now’s the time to note that he argues that Tsai “has been tired of cinema from the get-go, or at least the kind of cinema that attempts to excite us with strenuously subjective ‘storytelling.’ As rigorous an image-maker as he is, Tsai’s has always been a distant and tired cinema; he is, in fact, one of our preeminent movie-poets of the weariness engendered by late capitalism. Though Rebels is superficially more energetic than subsequent films, it is still an expression of—and reflection on—existence as exhaustion.”

But “Tsai’s films can also be very funny,” argues Gary M. Kramer, introducing his interview in BOMB, adding that “in his most audacious film, The Wayward Cloud (2005), Lee is dressed up (or more accurately, mostly undressed) as a dancing penis for one vivid musical number…. Lee’s characters are almost always named Hsiao-kang, a name that seems to be a merging of the filmmaker’s and actor’s in the fictional world of the cinema. Unlike Truffaut and Jean-Pierre Léaud’s Antoine Doinel, it’s not clear that Hsiao-kang is the same person across multiple films, though he does overlap in the features What Time Is It There? and in The Wayward Cloud, which are linked by the short film, The Skywalk Is Gone (2002). What is most consistent about Lee’s work in these films, apart from his character’s name, is the astonishing variety of his performances.”

Tsai’s “films, though inevitably marked by the locales and specific circumstances of when they were shot, attain a timeless quality through their refusal of outright resolution, often leaving characters, seemingly, as their plights have just begun,” writes Clayton Dillard, introducing his interview for Slant. “As such, it would be a great, and fitting, irony for Tsai’s first film to be released as his last.” And of Rebels, he writes that “the entirety of Tsai’s debut feature unfolds like a rebuttal to Jean-Luc Godard‘s Breathless, seeking to interrogate questions of pop-cultural influence not as a matter of homage or allusion-based deconstruction, but as a damning treatise on the nature of product placement, globalization, and the often innocuous ends of cinematic play. Each of these potentially disparate lines of inquiry unfolds with a remarkable clarity with regard to precisely how, in practice, youthful proclivities are inextricable from exploitative forms of corporate capital.”

Huei-Yin Chen also interviews Tsai—for Film Comment: “Tsai portrays what you might call his characters’ mindscapes, and undertakes an exploration of the potential of and possibility of cinema, the history and identity of cinema, and his own memories of the medium. With his iconic body of work, he has created an inner time that belongs to him alone and that further transforms every single aspect of his film world.”

James Kang is tending to an excellent entry at Critics Round Up on Rebels, collecting not only fresh reviews but also more than a few that date back several years. Let’s make note of a few more that’ve appeared in the last week or so.

“Tsai’s work sees generational defiance as a symptom of the ennui felt by their young subjects as they drift into adulthood, and Rebels’ unusually sharp focus on that theme makes it an accessible primer for the elements that would inform the more oblique masterpieces to come,” writes David Ehrlich in Time Out New York. “The long takes would get longer, the torrential downpours would get wetter, and the sex would get weirder, but each was clearly there from the start, and the local specificity of this detail-rich first effort makes it uniquely capable of illustrating why all of Tsai’s movies resonate with such universal feelings of alienation.”

At the AV Club, Mike D’Angelo adds that “almost every preoccupation that will dominate subsequent films like The River, What Time Is It There?, and last year’s Stray Dogs appears here in embryonic form.” In a similar vein, the Dissolve‘s Scott Tobias: “He’s not quite the assured, rigorous stylist he would become just two years later with his follow-up, Vive L’Amour, but he knows exactly where he’s going.”

“But Rebels is also very different from what would follow,” argues Jonathan Romney in Film Comment: “it’s punchier and grittier, with roots in the realist TV dramas that Tsai had made after moving to Taipei from his native Malaysia. In Rebels, he has said, he wanted to be ‘even more documentary, even more real about everyday life in Taipei,’ and what he achieves here is to inject rough-edged realism with a dash of punkish glamour.”

Updates, 4/10: A.O. Scott in the New York Times on Rebels: “Tsai typically uses narrative as a tool for exploring the moods and meanings that link his characters with one another and with the city that awakens, contains and frustrates their desires. They seem very much stuck in their world, but because that world is the creation of a wildly original artist coming into his own, it also feels alive with possibility.”

More from Jake Cole at Movie Mezzanine: “As with Antonioni, Tsai contrasts the overwhelming speed of modern consumerism with a reactionary wave of human primitivism as people regress in their ability to cope. The sexual urges of the brothers override socialization in favor of gratification, and violence sweeps through the film infrequently but with great force.”

“With Vive L’Amour,” writes Nicolas Rapold at Reverse Shot, “the films of Tsai Ming-liang forever became stories of space as much as of people: the siamese flats joined together in The Hole, the anonymous steam rooms of The River, the amniotically lit family apartment of What Time Is It There?, the movie theater and hallways of Goodbye, Dragon Inn. Compared to these later works, the orbits of Rebels of the Neon God are less constrained, the terrain more incidental, and even the globetrotting What Time Is It There? is threaded tight with a telephonic-chronographic linkup.”

Updates, 4/12: Rebels is Tsai’s “most accessible film,” writes Matt Zoller Seitz at RogerEbert.com. “That will seem like a funny observation once you’ve seen it, because Tsai’s most accessible film is more unusual and uncompromising than any you’re likely to see this year.”

Christopher Bourne has more on Rebels and, in another entry, writes: “One of the most interesting things about Tsai Ming-liang’s filmmaking career, considering what an inimitable and uncompromising artist he is, is the fact that three of the ten features he has directed to date have been commissioned projects.” The first of these is The Hole, which, “despite the pre-millennium tension that permeates it, and the familiar crying and despair that exists in its world, is Tsai’s most light-hearted and hopeful film. And although Tsai would disagree, a shaft of light suggesting a passage to heaven, a proffered glass of water, an outstretched hand, and a final love song from Grace Chang, all lead to what is as close to a happy ending as you’ll find in Tsai Ming-liang’s oeuvre.”

Tsai’s Journey to the West (2014) screens from May 5 through 7 at Anthology Film Archives.

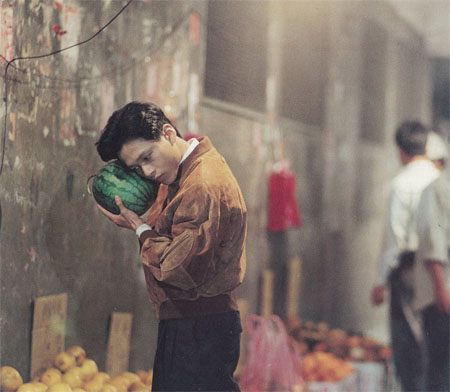

“If one were to see The Wayward Cloud as her or his first Tsai Ming-liang film, one might mistake him for another Asian ‘Extreme Cinema’ provocateur,” suggests Reverse Shot co-editor Michael Koresky. “Alongside the still-frame set-ups and studied pacing, there’s a gross-out extravagance that recalls Takashi Miike, and there’s even a helping of Jacques Demy thrown in for good measure. But if you’ve already seen every other Tsai film, then you’ll notice many of the director’s trademarks; there are elements of The Hole (there’s a water shortage in Taipei), Vive L’Amour (that film’s playful game of watermelon bowling here becomes a painful, sloshy bout of watermelon balling), and What Time Is It There? (hints that the two principal characters are the same as those from that earlier masterwork). Yet this film pushes Tsai into heretofore unseen realms of visual flourish and experimentation. The Wayward Cloud feels like Tsai’s least perfect film… and also his boldest.”

Update, 4/13: It’s Nick Pinkerton again, only this time in Reverse Shot and writing specifically about Rebels, “the most spot-on portrait of the fluorescent mall culture of a decade past, and of its attendant adolescent anomie (the characters in Rebels seem to be mostly around 20, but boy does this movie feel eighth grade to me), that I have ever seen, and few of the setting’s fetishes, trinkets, and images are untranslatable between hemispheres. The cut-off shorts, the bluffed arrogance, the gaudy costume jewelry, the weird, religious parents, the hours of Tetris, the lighter burns on skinny biceps, the ‘What are we gonna do with her?’ drunk girl on rubbery legs, and the tee-shirts tucked into powder-blue denim are all present, and all adorning a deep, lugubrious emotional base.”

Updates, 4/16: Josh Safdie at the Talkhouse Film on Rebels: “It’s arguably one of the greatest and boldest debuts in film history, and I am ashamed to say I am only seeing it now for the first time. Thank you, time. The vibe, the faces, the framing, the now, the neon… Tsai is an original, an original who works to code. I have read that the style of the film was born out of the discovery of the film’s lead actor, Lee Kang-sheng, and the pace at which he moves and acts. This is systematic, this is architecture and artistry at their finest.”

Viewing (6’14”). Tsai Ming-liang: The Hunger is a short film by Reverse Shot editors Michael Koresky and Jeff Reichert: “His movies may be spare and melancholy, but they make us feel anything but empty.”

Updates, 4/25: “The urban alienation that Tsai depicts is not just any alienation,” writes Moira Weigel for n+1:

[I]t belongs to the Rising Asia of the present, to the kinds of shoddy environments that the city renews too quickly and the typhoon rains erode…. There is a great scene in Rebels of the Neon God when Hsiao-kang pauses in the arcade, where he has been following Ah Tze and Ah Bing, and stares at a poster of James Dean. It’s a black-and-white image of that famous still from Rebel Without a Cause, where Dean leans back against a wall, staring cockily at something off to the right, his signature red jacket half-unzipped, and flicks a cigarette. This is an allusion to the European New Waves as much as it is to Hollywood—to the love that Truffaut and others expressed for Nicholas Ray. The longing gaze that Hsiao-kang casts at James Dean suggests an echo of the ambivalent desire that Tsai’s European heroes once felt for America, and the liberation that it represented. But Dean’s—or Truffaut’s or Godard’s—particular form of macho rebellion isn’t available in Taipei in 1992. The kids who scrape by stealing coins from arcade video games move among a different culture of images…. The new gods were digital. And they were already everywhere.

For Reverse Shot, Nick Pinkerton interviews Tsai, who tells him: “From my point of view, cinema’s departure from the movie theater is part of a natural progression of things, just like contemporary art is escaping the gallery.”

Also in RS, Fernando F. Croce on a scene in Face featuring Jeanne Moreau, Fanny Ardant and Nathalie Baye: “Wackiness does not necessarily spring to mind when thinking of the Malaysian-born, Taiwanese-raised Tsai, whose films… feel like the sheer soul-crushing weight of the world is forever bearing down on them. And yet this fleeting interlude featuring the trio of Gallic art-house doyennes hums with palpable giddiness, with the tickle of a cinephilic in-joke shared among friends and, more saliently, with a delighted sense of human connection. When the camera returns to this room, it finds it vacant except for the faint, off-screen sound of Moreau singing. Here today, gone tomorrow. Only a filmmaker so obsessed with life’s leaden materiality could also be so sensitive to its emotional evanescence.”

And from the RS archive: Pinkerton on Stray Dogs and Eric Hynes on What Time Is It There?

Christopher Bourne notes that Journey to the West “consists of 14 shots, most of them relatively brief, save for two lengthy centerpiece scenes. It begins with a very long shot, a nearly ten-minute close-up of Denis Lavant’s face as he is reclining. With the only sounds on the soundtrack Lavant’s labored breathing, we are invited to contemplate every wrinkle and crevasse on Lavant’s uniquely craggy visage. In this and every subsequent shot, Tsai challenges us to view images in a very different way than we are used to, the regard the act of seeing as a sort of contemplative meditation, the slowness and austerity of the shot forcing us to engage actively with the image, rather than be a passive consumer, as in most other films. In this goal, Tsai succeeds immensely, with exquisitely composed artistry and rather unexpected humor.”

Jeffrey Dunn Rovinelli in the L on Goodbye, Dragon Inn: “Tsai’s feature was expertly pitched towards the rapturous critical reception it (deservedly) received. Coming at the cusp of the much-fabled ‘death of cinema’ and folding sheafs of time and legend into an autoerotic ouroboros of cinema spectatorship, perhaps it mirrored the emotional life of many critics, even those that weren’t hunting for gay couplings in the bathroom as one central character does here. (Maybe they should try?) What that reception hid, however, is just how punk it is, and just how deep that eroticism goes.”

“No longer simply a cult classic, Rebels of the Neon God is part of the history of gay youth consciousness in popular culture,” argues Armond White in Out.

Update, 4/27: Once again, Nick Pinkerton for Reverse Shot: “At its best Goodbye, Dragon Inn does much more than pine for the impossibly grand movies of our memory; Tsai recognizes, respects, and loves the sweet melancholia born of unattainable longing far too much to buy it wholesale.”

Update, 5/10: For Little White Lies, David Jenkins talks with Tsai about Stray Dogs. And now that it’s opened in the UK, we have more on Stray Dogs from Peter Bradshaw (Guardian, 3/5) and Mark Kermode (Observer, 3/5).

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.