On June 27, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences will present the west coast premiere of the full-length version of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), newly restored by the Academy Film Archive in association with the British Film Institute, ITV Studios Global Entertainment, and the Film Foundation: “Powell’s widow, Oscar-winning film editor Thelma Schoonmaker, served as the supervising consultant on this restoration, alongside Film Foundation founder Martin Scorsese. Schoonmaker will introduce the Academy’s screening of the work that critic David Kehr has called ‘very possibly the finest film ever made in Britain.’” Meantime, Park Circus has been taking the restoration on a tour of theaters throughout the UK.

“It’s impossible to think of a contemporary British director or writer-director team making six consecutive masterpieces as did Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger when they followed The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) with A Canterbury Tale (1944), I Know Where I’m Going! (1945), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948),” writes Graham Fuller at the Arts Desk. “Not only does the industry no longer have the means to support such an iconoclastic partnership—there has never been a writer working in the mainstream national cinema as imaginative or as fertile as Pressburger and a director with such visual genius as Powell. (http://armstrongpharmacy.com) Variously suffused through pastoralism, Celticism and Gothicism (not forgetting Freudianism), these films brought British cinema to its Romantic climax.”

“Only one war movie to date has managed to create a psychologically believable German,” argues Philip Oltermann in the Guardian. “Blimp stars Roger Livesey as a young officer fresh out of the Boer war, who believes ‘clean fighting and honest soldiering’ will always win out in the end. On a trip to Berlin, he causes a diplomatic incident in a beerhouse and is challenged to a duel by a young Uhlan officer, played by Anton Walbrook. Both survive but end up in the same hospital, where they become friends. Jumping from the start of the century to the battlefields of Flanders, and finally to blitz blackouts, the film’s mission is to show how Livesey’s character got his Blimpishness—that is, became the archetype of the reactionary upper-class officer as lampooned in David Low’s cartoons in the Evening Standard. But actually it’s his friend who goes through real change: initially dreaming of revenge after the war, then, in 1943—when German revenge fantasies are in full swing—returning to Britain to flee the Nazis, a journey that Vienna-born Walbrook, real name Adolf Wohlbrück, had himself made only a few years previously. His speech in front of an immigration officer is still the most lyrical hymn to Britain’s lone role in that war ever captured on film.”

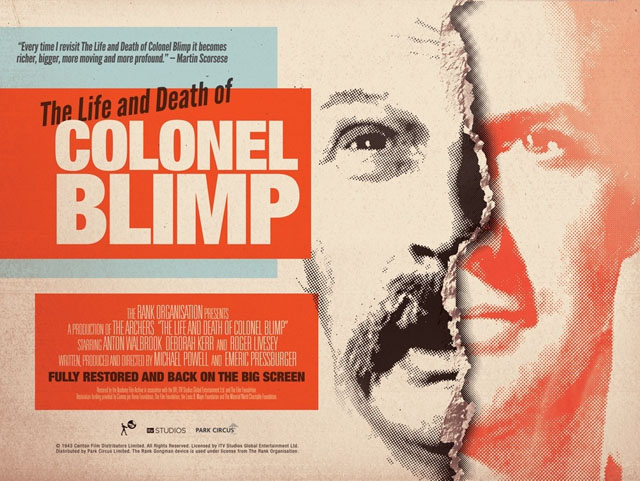

In a piece for the Telegraph on Churchill’s (failed) efforts to have Blimp banned, Marc Lee eventually works his way to Scorsese’s comments on the film: “Every time I revisit The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, it grows; it becomes richer. With every passing interval of time—and that’s what the film is about, after all—it seems to have become more resonant, more moving, more profound. You could say that it’s the epic of an ordinary life. And what you retain from this epic is an overpowering sense of warmth and love and friendship, of shared humor and tenderness, and a lasting impression of the most eloquent sadness.” Adds Lee: “As for the then prime minister’s close interest in the film—he was, after all, busy leading a nation at war—could it have been that, with a personal history that paralleled Candy’s in many ways, Churchill feared he himself was a Blimp?”

In a brief piece for the Guardian last month, John Patterson reflects on “the mysterious magic of Powell and Pressburger. Together they seem to me simultaneously the most English of filmmakers—their very subject, after all, is Englishness—yet their movies display an audacity that in their time may have seemed defiantly un-English. Consider beleaguered little England in 1943—Churchill’s ‘the middle of the tunnel’—then stare at The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp‘s vivid and blazing Technicolor, and marvel at the disconnect. That disconnect is less surprising when you recall that, as Powell himself once pointed out, Blimp had a Hungarian writer, a German-Jewish composer, a Czech costume designer, a German art director, a French cameraman, and its leads were Welsh, Scottish and Austrian: hey, it takes all sorts. To discern and anatomize the meaning of Englishness, you need outsiders, with their quizzical perspectives.”

More on Blimp from Peter Bradshaw (Guardian, 5/5), Dave Calhoun (Time Out London, 5/5), Philip French (Observer), and Wally Hammond (Little White Lies).

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.