“Alongside our week-long run of his new feature, Bestiaire, we present a retrospective devoted to the films of Denis Côté, one of the most gifted of contemporary Canadian filmmakers,” announces New York’s Anthology Film Archives. “Demonstrating different approaches to storytelling and tone, and moving freely from fiction to nonfiction, as well as exploring the porous border between them, Côté’s films are unified above all by their perceptiveness, patience, and visual beauty.”

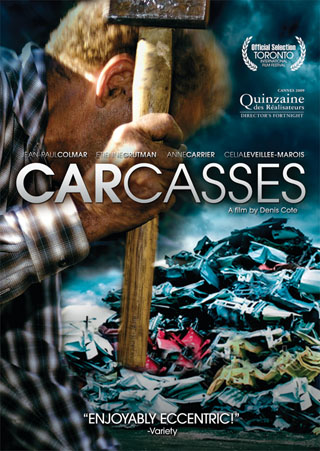

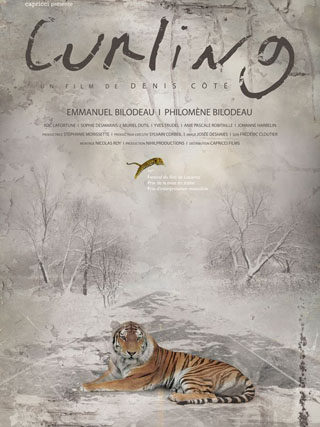

Back in 2010, Jason Anderson interviewed Côté for Cinema Scope, writing in his introduction: “Remarkably productive given the soul-crushing circumstances of the Canadian film industry for established filmmakers and newcomers alike, Côté has made five features and several shorts since 2005. Two best-director wins at Locarno (including one for Curling), the appearance of last year’s superb Carcasses at the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, and this year’s Les lignes ennemies, shot for the omnibus Jeonju Digital Project, have established him as perhaps the best-traveled of young Canadian filmmakers…. Thanks to the often confrontational nature of his tough, frankly intimate drama Les états nordiques (2005) and Nos vies privées (2007) and the uncategorizable weirdness of Carcasses, Côté’s films have proven to be a better fit with adventurous festival programmers than those of most of his contemporaries.”

In the L this week, Tomas Hachard recommends catching Carcasses, which, whether or not you’re in New York, you can do here on Fandor: “Jean-Paul Colmor works from home in rural Quebec. Home, though, includes an expansive yard filled with old cars, and work entails sorting through them and selling used parts to occasional customers—so long as they don’t try to bargain too much. Colmor is certainly a bizarre subject, in manner as well as livelihood, but Carcasses begins, at least, as a tender profile that emphasizes the joy he finds in work and isolation.” Eventually, Carcasses “warps into narrative fiction. Côté offers few answers for this switch, but what results is a wonderful hybrid of a film.”

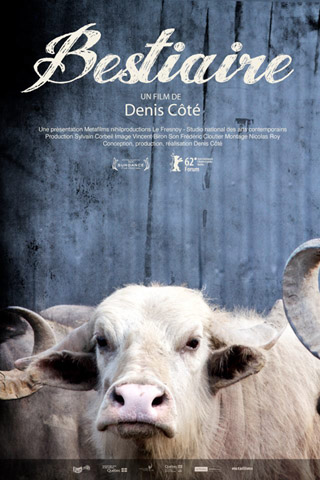

Bestiaire is “a film about animals, but to simply say this is to wander out into a shitfield of slippage,” writes Michael Sicinski in MUBI’s Notebook. “How can we ever look at or talk about animals without really making statements about ourselves, our own desires?” The film “begins with a life drawing class, in which students are working from taxidermy. Then, Côté takes us in and around Quebec Zoo, where he asks us to just spend some long-take time in their company. There is a sadness and dignity to these scenes that is legible but almost certainly not there. I am describing human feelings. But compared to the work of Bert Haanstra (‘maybe we’re the “animals”!’) or Nicolas Philibert (‘there is so much there we can never know’), Côté uses his film to place all of us at a respectful distance, and keep us there.”

“Without narration and talking heads, the movie gleams with the veneer of objectivity, a word that Mr. Côté has employed as a term of value when discussing the movie,” notes Manohla Dargis in the New York Times. “‘People want you to take sides,’ he said in an interview with a Montreal newspaper, adding that he wanted people to make up their own minds. If he was after objectivity, as in impartiality and neutrality, he fails in Bestiaire, a movie that carries his subjective stamp in each shot and edit. It could not be otherwise. As the documentary filmmaker Emile de Antonio has observed, ‘As soon as one points a camera, objectivity is romantic hype.’… At the same time, he doesn’t seem interested in making an animal-rights movie, even if, willingly or not, that is precisely, what he ended up with…. It may not be pretty, but it is essential viewing.”

Melissa Anderson in the Voice: “That I, a fan of the four-footed, could not identify the names of many of the creatures in Bestiaire would seem to prove the point that the English Marxist critic John Berger makes about the marginalization of animals in his influential 1977 essay ‘Why Look at Animals?’; the treatise’s title itself seems to be the starting point for Côté’s film…. Like Nicolas Philibert’s documentary Nénette (2010), about the star-attraction orangutan at a Paris zoo, Bestiaire exposes the mechanics of a strange, multi-layered voyeurism: watching animals watch—or, more accurately, look past—those who gape at them.”

Côté himself mentions Nénette when looking back on the films focusing on animals that he’s admired in a piece for Cinema Scope. Among others are Barbet Schroeder’s “very beautiful” Koko, A Talking Gorilla (1978), Werner Herzog’s “incredible” Grizzly Man (2005), Artavazd Pelechian’s “overlooked masterpiece” The Seasons (1975), and Michelangelo Frammartino‘s Le Quattro Volte (2010)—”Doesn’t its unanimous success have something to do with its refusal to give a conscience other than a utilitarian one to its animal-protagonists?”—as well as Ilisa Barbash and Lucien Castaing-Taylor‘s Sweetgrass (2009) and Emmanuel Gras’s Bovines (2011). As for his own Bestiaire, “I won’t announce my conversion to the Church of James Benning but I must admit that I worked in reaction to many things. In reaction to the literariness of my last film, Curling (2010). In reaction to whatever we consider trendy; in reaction to entertainment, to anthropomorphism, and the informational. More generally, I also tackle things ‘by negation,’ by telling an actor not to do such and such things without revealing to him or her exactly what I want; by whispering to my DOP ‘everything except for that.’ Thus, the idea of Bestiaire naturally came from a series of constraints, of refusals, perhaps even from the negation of the idea of subject matter itself.

Writing for Sundance NOW, Anthony Kaufman notes that “many of Côté’s cinematographic static compositions are distinctly offset: little horses amble in and out of the frame; horns sneak into the lens, with no body in sight; other animals are obscured, either by the film’s frame or other objects inside the mise-en-scene. Rather than ‘capture’ the animals with the camera, this strategy allows them to roam freely, as it were, within the spaces of the film. Yet at the same time, these shots arguably call attention to our viewing of the animals, making the audience complicit in the kind of voyeurism that Côté appears to be investigating.”

Calum Marsh in Slant: “Like Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel’s extraordinary Leviathan, Bestiaire submerges us within a rigorously organized commercial system while pointedly effacing the details of its daily operation, so that a doc ostensibly concerned with a sprawling outdoor zoo more closely resembles, in practice, an abstraction attuned to the rhythm of the environment rather than its functional mechanics. Its purpose isn’t our edification: By the end of the film we understand how a place like this operates about as well as the lion understands why it’s caged.”

Update, 10/29: Tomas Hachard for Guernica: “Côté’s films prior to Bestiaire are set outside modern, urban life, in assorted towns around Quebec: places where people escape to, places where expired junk goes to rest, places so stifling that residents yearn to run away, but also places where rebirth might be possible…. All That She Wants (2008), Côté’s most compelling narrative film, details, in gorgeous black-and-white cinematography, the corruption of a one-road town. The sound of cars speeding by on the nearby rural highway occasionally overtakes the otherwise dominant wind chimes and buzzing bugs. Meanwhile, in town, a passing vehicle generally only means trouble. The resident small-time gangsters and pimps have no real power, but their fights over who gets to rule over two tracts of farmland causes no less pain than if they did…. Each of Côté’s films prior to Bestiaire runs up against the limits of human control.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.