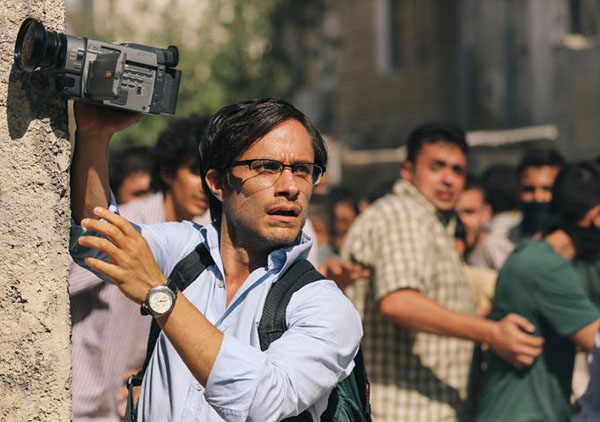

“For a film about a journalist being unfairly held in solitary confinement by one of the globe’s most politically divisive governments, Rosewater is notable for its modesty and emotional restraint, for its principled refusal to sensationalize its potentially inflammatory subject matter,” begins Tim Grierson, writing for Screen Daily. “The directorial debut of veteran Daily Show television satirist Jon Stewart, this sensitive, stripped-down drama documents the four-month ordeal of Iranian-Canadian Newsweek reporter Maziar Bahari, who in 2009 was arrested in Tehran while covering the country’s presidential election. A certain narrative conventionality is perhaps inevitable with this type of material, but Rosewater is helped immensely by Gael García Bernal’s assured, lived-in lead performance.”

“Stewart (whose prior screen credits consist of supporting roles in a string of forgettable ’90s comedies) may seem like a left-field choice to adapt Bahari’s 2011 memoir, Then They Came for Me,” grants Variety‘s Scott Foundas. “But in one of the story’s several stranger-than-fiction twists, an appearance by Bahari on The Daily Show ended up being used by his jailers as evidence of treason…. That was in 2009, during the run-up to the Iranian presidential election that pitted incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad against reform-minded opposition candidate Mir-Hossein Mousavi…. There is something of Polanski in the movie’s intentionally claustrophobic tension, and a tone held in careful balance between despair and gallows humor…. Though we know going in that Bahari will live to tell his tale, Stewart maintains a serenely unsettling tension throughout. Perhaps more impressively, he’s made a movie of the moment that doesn’t feel like a sententious ‘issue’ drama, and is all the more affecting for it.”

Todd McCarthy in the Hollywood Reporter: “The way the story unfolds, there really isn’t a message per se other than a general one about not giving up hope; the political and personal lessons here don’t seem particularly profound or instructive. Stewart and cinematographer Bobby Bukowski cover it all in a straightforward, watchable way, the performances are all sincere and solid and the situation is easy to respond to emotionally. But as a case history in the annals of political repression, it feels like a bit of a side show.”

For Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn, Rosewater “suffers from the director’s underwritten screenplay and several misconceived narrative devices…. But it’s also so committed to a good-natured attitude about the power of perseverance that the many shortcomings register as inoffensively well-intentioned rather than exclusively shallow. Imagine a rousing Daily Show episode without the jokes. Rosewater is lacking in sophistication, but its attitude is infectious.”

“And Rosewater hits a deliciously surreal note when Bahari begins to drive his captor crazy by fabricating stories about how his globe-trotting journalism was really a cover for an addiction to sensual massages,” writes Steve Pond at TheWrap. “If one is to believe Rosewater—and in this case, I really want to believe it—there’s at least one jailor in Iran who now believes that Fort Lee, New Jersey is a hedonistic sexual playground of staggering proportions. Those scenes, and others in the movie’s homestretch, have an energy, style and flair that is sometimes lacking in the rest of the film. The final scenes then return to a more earnest approach as they pay tribute to the journalists imprisoned around the world ‘for the crime of bearing witness’—but then, a little earnestness may be what this material needs, even if it’s not what we’ve come to expect from Stewart.”

Update, 8/29: “The truth is, he was not planning to direct Rosewater or even write the screenplay.” Marisa Guthrie profiles Jon Stewart for a Hollywood Reporter cover story.

Update, 8/31: “Stewart clearly wanted to make a people-have-the-power message picture that would resonate at least as much with American youths as longtime students of political repression in the Middle East,” writes Chris Willman at the Playlist. “That transparent desire to make the material as accessible as possible to U.S. moviegoers—starting with the old-fashioned notion of having all the Iranians speaking to each other exclusively in English—results in a sometimes overly slick take on potentially tough subject matter. For better or worse, torture-themed films don’t get too much easier to take than this one.”

Update, 9/2:

Update, 9/4: “The humor and drama don’t neutralize each other,” writes James Rocchi at Film.com. “[I]n what’s perhaps Stewart’s most successful achievement as a director, the changes in tone work in a harmony, not at cross-purposes.”

Update, 9/5: “Stewart’s film will undoubtedly be mistaken for a work of great ‘relevance’ in the wake of the horrible incidents involving Western journalists and ISIS,” writes Jim Hemphill at Filmmaker, “but his movie is benefiting from these tragedies, not exploring them—there isn’t a single scene in Rosewater that will challenge or enlighten anyone in the audience who has ever picked up a newspaper. The audience and critics at Telluride seemed to embrace it, but to understand what a failure Rosewater is at every emotion and idea it tries to generate—suspense, humor, a dissection of a rigged political system, etc.—one need look no further than a previous Telluride entry starring Bernal, the exquisite and far superior No.”

Update, 9/9: “Blame it on the efficacy of black humor, a staple of Stewart’s repertoire, but the psychological perversities endured by Bahari in captivity which his memoir more vulnerably exposed (e.g., his desire to be beaten for the sake of human contact) are elided in favor of the tale’s more absurdist elements,” writes Jay Kuehner for Cinema Scope. “The cultural revolution might be tweeted, with the strains of Leonard Cohen drowning out the rosewater scent of an historical piousness, but the dignified resistance of victims like Bahari (and those many still imprisoned) ought to be etched into our conscience far longer than just an Oscar season. But then again, credit Rosewater for troubling itself over just what makes the axis, evil or otherwise, spin.”

Updates, 9/12: Rosewater “is leaden with earnestness,” finds Grantland‘s Wesley Morris. “Bahari’s imprisonment is so clearly absurd that you wish Stewart had risked treating it absurdly, that he would try for a kind of moral farce…. Chiefly, though, the movie opts for grace. It wants to be taken seriously. So you get a decent, heartfelt, competent film that—in demanding our outrage against injustice—doesn’t believe, as a film, that it has a right to ask more of itself.”

But for Owen Gleiberman, now with the BBC, Rosewater “is one of the most incisive movies about the post-9/11 world ever made.” Stewart “turns out to be a ’70s classicist, deadly sincere not just about his subject but about doing everything possible to capture the full, revealing truth of it on screen. Stewart works with astounding confidence and skill; he’s a born storyteller with a gift for sculpting drama out of the smallest actions.”

For Jake Cole at the House Next Door, “the numerous scenes of Bahari having hallucinatory conversations with his dead father and sister smack of clumsy dramatization of the journalist’s internal debate, a result of Stewart’s lack of greater facility with actors or the camera. Furthermore, the joyous ending only makes slight consideration for the man seen entering the torturer’s cell after Bahari, a man who won’t enjoy the relative safety of being a well-known journalist with international attention. The film celebrates Bahari emerging rattled though mostly unscathed, but I couldn’t help but feel only dread for that man taking his place.”

More from Linda Holmes (NPR), Paul MacInnes (Guardian, 3/5) and Joe Reid (Wire). Interviews with Stewart: David Fear (Rolling Stone), Jeff Labrecque (EW) and Brian Tallerico (RogerEbert.com).

Updates, 9/14: “The same liberal idealism that’s informed Stewart’s sharpest on-air jabs guides this movie toward maudlin bathos and corny truisms about how repressors are themselves repressed,” writes Ignatiy Vishnevetsky at the AV Club. “It’s completely sincere and mostly toothless, springing to life only in scenes where Bahari is being questioned by his unnamed interrogator (Danish actor Kim Bodnia, best-known Stateside as the star of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Pusher; the movie is notably short on actual Persians), and then only occasionally.”

“Rosewater never develops into anything unexpected or special,” agrees Noel Murray at the Dissolve. “Bahari’s story is one people should hear, and Stewart tells it just fine (with a lot of help from Bernal), but the movie seems to hold back from making audiences uncomfortable, and without that harshness it’s just a recounting of events, not a you-are-there experience.”

Update, 11/3: Rosewater “could be seen as a bridge between Stewart’s TV present and his undefined but rapidly approaching future,” writes Chris Smith at the top of an interview that’s landed on the cover of New York. “The comedian has sat behind the anchor desk of his multi-Emmy-winning Comedy Central show since 1999, but his contract ends next fall and he is uncertain whether he wants a new one. Now, over two conversations in October inside the show’s 11th Avenue studio, Stewart reflects on his life in the satirical-news business and the legacy The Daily Show will one day inevitably leave behind.”

Updates, 11/12: “Blindfolded in anonymous, talcum-colored rooms, Bahari’s incarceration is a spectacle of dull repetition, his nameless handler (Kim Bodnia) dressing him down in a whirlwind of accusations both tenuous and impossible to disprove,” writes Steve Macfarlane for Slant, noting that “the real-life Bahari nicknamed this man ‘Rosewater,’ after the unmistakable scent of his perfume…. Bahari’s final scene with his father’s ghost is a passionate argument, every bit as subtle as it sounds: The young prisoner explains that a gulag is a gulag, whether it’s Stalinist, capitalist, or Islamist. (That the real-life Rosewater’s father was also imprisoned by the Shah is weirdly elided from Stewart’s adaptation.) Perhaps for the wiser, Rosewater shrugs off the bigger questions about Iranian politics its first half appears to raise, falling back instead on a gestalt of the eternal, Kafkaesque regime, wherever the viewer may find it.”

“In outline, Rosewater sounds earnest, one-note, relentless—something you’d watch out of a sense of duty,” writes New York‘s David Edelstein. “But it turns out to be a sly, layered work, charged with dark wit along with horror.”

“Laughing at the horror is a natural reaction for Stewart,” writes Tasha Robinson for the Dissolve. “It’s also a tremendously effective one here.”

“We all know Stewart is a smart guy who’s good at talking,” writes Stephanie Zacharek in the Voice. What’s surprising is how good he is at filmmaking. Stewart “understands that even a story relying largely on dialogue, as this one does, also needs to be cinematic…. Rosewater isn’t one of those nicey-nice vehicles that takes pains to remind us that some people are just culturally ‘different’ and thus can’t be held responsible for adhering to warped religious and political dogma. Instead, Stewart puts it pretty plainly: Some people are just idiots, and the stupidity of evil can kill you. Thank God Bahari managed to outsmart it.”

“Stewart turns out to be a merely okay director,” finds Time Out‘s Joshua Rothkopf. “Give him another movie or two. He’s made a promising start, with blackly comic greatness in his grasp.”

“There are moments of real power here, of well-articulated fury and moral ambiguity, surrounded by choices that are downright puzzling,” finds Flavorwire‘s Jason Bailey.

Updates, 11/13: “The problem with most slogan flicks—movies that try to get their audience all heated up about an issue—is that they’re meant to be easily digestible, which politics rarely are,” writes Ignatiy Vishnevetsky at the AV Club. “Cut out popular appeal altogether, and you end up with one of those little, airtight dialectical materialist boxes, which are pretty much unimpeachable in terms of political form, but which the average viewer doesn’t want to get into. Overdo it, and you end up with centrist mush—basic, boilerplate human-interest stuff that’s too shapeless to completely work as drama, and too depoliticized to be taken seriously as anything else. In other words, a movie like Rosewater.”

Time‘s Richard Corliss: “‘For Lubitsch,’ critic Andrew Sarris famously wrote of director Ernst Lubitsch’s 1942 anti-Nazi farce To Be or Not to Be, ‘it was sufficient to say that Hitler had bad manners, and no evil was then inconceivable.’ For Stewart, it was enough to say the Iranians can’t take a joke.”

“Stewart’s slyly written script avoids the stiffness of so many political dramas in which the characters function mainly as ideas (the kind of movie Rosewater threatens in its first 30 minutes to become),” writes Slate‘s Dana Stevens. “What develops between Bahari and Rosewater is specific to these two flawed, scared men, each convinced that his point of view is the just one and that sooner or later his interlocutor will have to break. Their perversely close connection—the dramatic heart of the film—is not only psychologically gripping but often hilarious.”

“The reason the trailer fails to sell Rosewater is that it doesn’t capture the film’s plentiful and dark sense of humor,” suggests Paul Constant in the Stranger. “Bahari is always joking around—with his pregnant wife, with a driver he hires to introduce him to the opposition party, even with the man the Iranian government has hired to torture the nonexistent truth out of him. He’s a funny man, and he recognizes the absurdity of his situation, first as he’s reporting on a rigged election in a country with no journalistic freedom and then as he’s trapped in a room for months on end with a moronic working-class torturer. The weirdness of the little details in Bahari’s memoir… help the film ring true and save it from overdramatic biopic hell.”

“Rosewater, along with his nightly mockery of the news, shows that freedom of the press has no greater champion than Jon Stewart,” writes Marjorie Baumgarten in the Austin Chronicle.

“For a movie about extended captivity, Rosewater is, if anything, too pleasant to watch,” finds Sam Adams in the Philadelphia City Paper. “It depicts Bahari’s fear without conveying it, letting viewers keep a comfy distance while tut-tutting foreign totalitarianism. It’s not wrong, but it’s easy.”

“The movie doesn’t announce the arrival of a born filmmaker, but it’s much better than a dilettante project,” adds Robert Horton in the Seattle Weekly.

New interviews with Stewart: Sam Fragoso (right here in Keyframe) and Andrew O’Hehir (Salon).

Updates, 11/14: For Godfrey Cheshire, writing at RogerEbert.com, Rosewater is a “gripping, intelligent directorial debut,” and he’s got a personal connection to it as well: “In 1997, on the first of several visits to Iran to investigate its cinema, I met a smart, genial young Iranian-Canadian filmmaker and journalist named Maziar Bahari. We kept in occasional touch thereafter and I followed his reporting on Iran in Newsweek, and was also impressed by his filmmaking, especially a chilling documentary called Along Came a Spider, about an unapologetic Iranian serial killer who preyed on prostitutes.”

“Working with the cinematographer Bobby Bukowski, Mr. Stewart gives the movie a run-and-gun tremble that’s familiar from documentaries and war movies,” writes Manohla Dargis in the New York Times. “This visual approach, along with the dusty, churning streets (with Jordan standing in for Iran), swirling crowds and looming images of Iranian leaders, contributes to the you-are-there authenticity that, at first, fights with some of Mr. Stewart’s other choices, including casting a well-known Mexican actor as his lead and having the Iranian characters speak in accented English.”

“Rosewater is neither subversive nor damning in its picture of blind faith, not to mention a completely inert representation of the political-film genre,” writes Glenn Heath Jr. in the San Diego CityBeat. “Each scene exists in a stagnant purgatory between satire and drama, never having the courage to choose one or the other. Aside from a few flashes of magical realism, Bahari’s story is aesthetically pedestrian, concerned more with the internal struggle of desperate men trying to reclaim the status quo of their lives.”

“If it weren’t for the name of its director, Rosewater would likely slip in and out of theaters without much fanfare,” argues Esther Breger, writing for the New Republic.

Updates, 11/17: “Once Bahari is in prison,” writes the New Yorker‘s David Denby, “Rosewater comes to creative life. Some of the cells, painted gray and white, are oddly shaped; one appears to be an irregular triangle. Bahari seems caught in a contemporary art installation. The hard-focus clarity of the images (Bobby Bukowski did the cinematography) leads to an intimacy with anguish that passes into expressionism.”

Iranian-American comedian/filmmaker Negin Farsad for Indiewire: “I understand why Jon Stewart cast Bernal—he’s talented, he’s a celebrity, he’s hot, he’s really good looking and he’s cute. My point is, I have a crush on Gael Garcia Bernal. Oh no wait, that’s not my point, my point is that while I understand why Jon Stewart made that choice, maybe he even had to—who’s going to fund a movie with an unknown Iranian actor as the lead?—what I don’t understand is that the internet didn’t seem to care that a Mexican was playing an Iranian. Or that Danish and Greek actors were also playing Iranians in Rosewater. Where is our threshold when it comes to authenticity in casting?”

Jason Gorber talks with Stewart and Bahari for Twitch.

Update, 11/23: “The odd thing about Rosewater is that—much like Ben Affleck’s Argo, another fact-based drama set in Iran—it’s a political film without any significant political slant,” finds the Chicago Reader‘s J.R. Jones. “Even Bill Maher’s Religulous (2008), wrongheaded as I found it, had a strong political perspective that forced me to examine my own beliefs. Rosewater, by comparison, often seems more like tap water. Stewart wants us to know that Islamic theocracy is the enemy of personal liberty, that international journalists deserve the utmost respect, and that families suffer terribly when their loved ones are thrown into political prisons. I agree with all that—and so, I imagine, does Bill O’Reilly.”

2014 Indexes: Telluride + Toronto. For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.