After Funny Ha Ha (2002), Mutual Appreciation (2005) and Beeswax (2008), Andrew Bujalski finally has a film at Sundance. Computer Chess—take a look at the terrific site, find the “secret teaser,” watch a few games, listen to a tune, read a book—premiered on Monday in the NEXT section, and so far, as with Park Chan-wook’s Stoker, reviews are pointing to a split verdict.

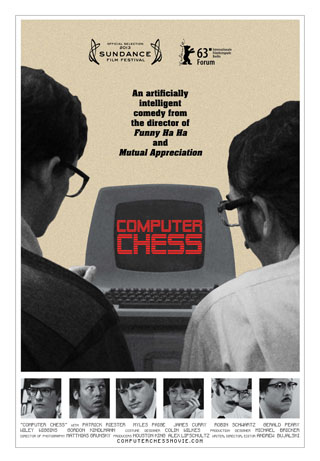

First, though, Mark Olsen‘s profile for the Los Angeles Times lays down a few basics: “A flaky, funny comedy set amid a weekend computer chess tournament sometime around 1980, the film was shot using black-and-white Sony video cameras from 1969, giving the film a hazy look and rangy feel that Bujalski says was inspired partly by photographer William Eggleston’s own 1970s video experiment, Stranded in Canton.” Bujalski tells Olsen he’d always been asked why he wasn’t shooting on video, and he eventually decided that “‘if I were going to do that I’d want to find some perverse and painful was to do it.’ … The cast includes Dazed and Confused actor Wiley Wiggins, film professor and critic Gerald Peary, and a pair of film editors and a few actual computer programmers making their acting debuts.” When “financing failed to materialize for a more conventional story that would have required a bigger budget and actual movie stars—’Ironically enough, in my mind, a Sundance kind of movie,’ he said”—he pulled out a filed-away eight-page treatment for Computer Chess: “‘It could not be a more absurd task,’ Bujalski said. ‘We have no money, I have no script, it’s on a topic I don’t know anything about, it’s got 30 or 40 speaking roles, which I have not cast, it’s a period piece and we’re going to shoot it on an experimental camera rig that we need to design from the ground up. And we start shooting in two months.'”

And Rooftop Films founder Mark Elijah Rosenberg loves this “hilarious comedy and a nostalgic period piece, layered by multiple levels of metaphoric meaning and social critique…. Bujalski’s deft script dances with about half a dozen different story lines, each fully realized, dramatic and funny. This completely masterful film is the rare film that is unfailingly entertaining and deeply insightful and intelligent.”

Time Out Chicago‘s A.A. Dowd, not so much: “Computer Chess plays like both a micro-indie Christopher Guest movie and a pre-Internet variation on the usual mumblecore theme of human interaction filtered through technology. It’s also largely a mess, with no dramatic stakes to speak of and only a handful of laughs. Still, I have to admire on some level Bujalski’s willingness to make something even smaller—and much stranger—than his previous output.”

At the AV Club, Sam Adams finds that after the “initial setup, the movie goes off the rails in several directions at once, detouring into a couples’ encounter group in an adjacent conference room whose rituals resemble the first hour of Jacques Rivette‘s Out 1, and frequently revealing a fluffy stray cat ominously prowling the hotel’s halls…. On the way out, my colleague Tim Grierson compared Computer Chess to Steven Soderbergh’s Schizopolis, a far more acute point of reference than the Waiting for Guffmans that have been floating around, but it’s Schizopolis without the underlying anger—or, to be frank, its boundless inspiration. Computer Chess is often hilarious, its unwieldy medium perfectly matched to its subjects’ social awkwardness, but for Bujalski, it feels like the start of a new direction and more like an abrasive palate cleanser.”

Writing for Screen, Anthony Kaufman argues that “Bujalski is clearly less interested in the game itself than the larger philosophical questions it brings up about artificial intelligence and the mind-body problem. During the first night of the competition, a handful of men from the conference smoke pot and debate the ramifications of sentient computer beings. Are humans learning from the computers, or more ominously, are the computers learning from us? Things get weirder…. At certain points in the film, the two worlds coexisting inside the hotel—the spiritual and the logical—collide with humorous results…. Computer Chess is ultimately unlike anything Bujalski has done before—and unlike just about anything anyone has done before. The film is likely to confound viewers, but it’s also a bizarre and fascinating retrograde portrait of an eccentric people and a faraway time.”

“It’s hard to keep track of all the moving parts in Computer Chess, some of which work better than others,” grants Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn. “Whenever it stars to wander, however, Computer Chess snaps back into focus with Bujalski’s typically assertive capacity to script naturalistic dialogue… Computer Chess excels at conveying the frustrations of feeling trapped by forces beyond one’s control, the complexities of humanity irresolvable by any neat code.” But the Hollywood Reporter‘s Todd McCarthy finds it all “as deadly dull as the event it covers.”

Interviews with Bujalski: Alexandra Byer (Filmmaker), Eugene Hernandez (The Daily Buzz), and Indiewire.

Updates, 1/26: First, the news. Computer Chess has won this year’s Alfred P. Sloan Feature Film Prize. “Now in its tenth year, the Prize is selected by a jury of film and science professionals and presented to outstanding feature films focusing on science or technology as a theme, or depicting a scientist, engineer or mathematician as a major character.” And for Indiewire, Alison Willmore reports that “AMC/Sundance Channel Global has picked up five films from the 2013 Sundance Film Festival for international broadcast on its European and Asian networks in conjunction with the second annual Sundance London Film & Music Festival in April. The company’s Gail Gendler negotiated deals for Andrew Bujalski’s Computer Chess, Sebastian Hofmann’s Halley, Matthew Porterfield’s I Used to Be Darker, Eliza Hittman’s It Felt Like Love and Chad Hartigan’s This is Martin Bonner.”

“There has always been a quizzically analytical element to Andrew Bujalski’s films, and it comes to the fore in Computer Chess,” writes the New Yorker‘s Richard Brody. As for the encounter group staying in the same hotel as the nerds, their “guru-like leader and his acolytes attempt to get in touch with their repressed erotic feelings and liberate their stifled intimacy, and Bujalski shrewdly pairs them as contrasting yet parallel modes of mind-expansion—knowing, as he does, that history proves the rise of the computer and its surrogate intelligence as an even more powerful tool for transforming the very notion of human identity.”

In Variety, Justin Chang argues that “this quasi-mockumentary is easy to admire in spirit even when its haphazard construction practically defines hit-or-miss. The result is about as weird and singular as independent cinema gets, an uncategorizable whatsit that makes Bujalski’s earlier low-budgeters look slickly commercial by comparison.”

Update, 2/3: “The dislocation caused by the physical aspects of the production, the weird haircuts, lingo, clothes and the black-and-white imagery transport you to a world that for sure existed but has never really been explored on the big screen with such texture,” writes Mike Ryan at Hammer to Nail. “Unlike other films of this period, Computer Chess doesn’t attempt to evoke warm fuzzy nostalgic feelings of a bygone era; instead, it uses the dislocation generated by the video image to cause us to be hyper-aware of how different the world was in the past from how it is now. Bujalski depicts an innocent computer age when the excitement of technology was driven by a pure pursuit of exploration, rather than the pursuit of application value.” All in all, Computer Chess is “an extremely entertaining low-tech cinematic breakdown of our modern high-tech world.”

Update, 2/10: Kino Lorber has acquired U.S. rights, reports Cameron Sinz at Indiewire.

Update, 2/13: “Bujalski really has pulled off something extraordinary here,” finds the Guardian‘s Andrew Pulver: “it won’t be to everyone’s taste, for sure—this is no War Games-style pop comedy. But as an act of cultural archaeology I can think of few better.”

Updates, 2/18: In the Notebook, Adam Cook finds that “for all its silliness, the philosophical questions at the film’s core, mockingly presented though they may be, carry a real weight.”

Twitch‘s Brian Clark: “At times it recalls Robert Altman’s wry, observational ensemble pieces—think Nashville, Health and Ready to Wear—but, ultimately, Bujalski makes the material his own, with an even looser, freer-flowing structure than Altman, a healthy dose of the psychedelic, and by going aesthetically where few filmmakers dare to tread.”

Update, 3/11: Here in Keyframe, Anna Tatarska talks with Bujalski.

Sundance 2013: Index to our reviews, reports, and coverage of the coverage. For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.