While Tarantino fans anxiously await Django Unchained, blogging every still issued from the set, New York’s Film Forum launches a three-week long series: Spaghetti Westerns.

“As gloriously violent and fun as these films are,” writes Joshua Rothkopf in Time Out New York, “they contain a secret critique, born out of love for—and dissatisfaction with—Hollywood’s heroic vision of itself, in movies like 1953’s Shane. By the time of the Johnson presidency, those films bore little relation to the America that was spraying down protesters and bombing the Far East.” He argues that “the real value of Film Forum’s series (co-programmed by Giulia D’Agnolo Vallan and Bruce Goldstein) is the way it provides a deeper understanding of the sociopolitical changes afoot. In movies such as Sergio Corbucci’s The Mercenary (1968) and Leone’s Duck, You Sucker (1971), you can sense a global revolutionary fervor in their plots’ Mexican dreamers that never would have gained traction in your average John Wayne horse opera. Working in an Italian studio system more accepting of horror, giallo and stylish nonsense, directors like Giulio Questi uncorked hellish hybrids like Django Kill…If You Live, Shoot! (1967), complete with scenes of corpse raiding and torture—a brutal vision of a selfish nation in its birth throes.”

In a piece for Film Comment (not online), J. Hoberman recalls more than a few fun nights out on 42nd Street “in the days when the soles of your sneakers stuck to the floor… No doubt that an irrational appreciation for the ultraviolent Italian Westerns we called Da Pasta is predicated on some specific sociohistorical coordinates. One, it’s all but vital to have been weaned on Westerns and to have internalized every genre cliché. Two, it’s pretty much a necessity to have been, if not a rabid Maoist, then at least deeply alienated from Richard Nixon’s Amerikkka. Spaghetti Westerns were as much a feature of the high Sixties as 2001 or Jimi Hendrix. The Black Panthers were supposedly big fans. Three, it was crucial to attend these rabble-rousing gorefests in their natural habitat. Seeing The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (67) as a college freshman in the decrepit, downtown theater across from the Binghamton, New York, bus station, was a revelation.”

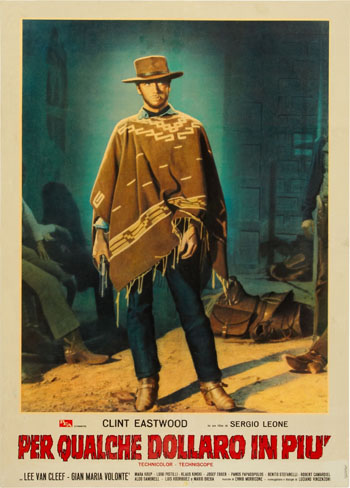

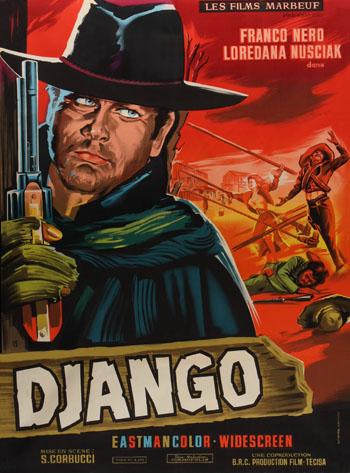

“Overviews of the spaghetti western inevitably begin with Sergio Leone, whose presentation of Clint Eastwood as the ultimate laconic Westerner grows more iconic throughout the genre-codifying trilogy of A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, The Bad and the Ugly.” Vadim Rizov at GreenCine Daily: “Time progressively slows to a mythic crawl, as mundane quick-draw showdowns and bounty hunter pursuits become epic set pieces through sheer duration…. While spaghetti westerns make use of the traditional site of a frontier town surrounded by wilderness, there’s never any space that—once finally purged of the uncivilized and murderous—can be expected to remain safe. The sense of a perpetually war-charged landscape is often made explicit in movies which make use of the Civil War and attendant lingering Mason-Dixon resentments. For Italians, their very own divide between the north and traditionally impoverished south finds a strong, deeply felt corollary here. In Sergio Corbucci’s 1966 Django, the subject is racism: the film unambiguously condemns it, and any methods used to end it are acceptable.”

Justin Stewart for the L: “Any substantial spaghetti Western rep series doubles as a tribute to composer Ennio Morricone, who was often ‘supervising’ scores if he wasn’t writing them, under his own name or presumably more international market-friendly aliases like Leo Nichols or Dan Savio. Awesome and instantly personalized as they are on their own, his radical, grunt-heavy concoctions achieve ineffable levels of coolness and beauty when paired with imagery of European character actors firing their way across the Apennine Mountains or a recycled dummy town in southeastern Spain. But a series like Film Forum’s also offers a chance for renewed appreciation for treasures like the actor Lee Van Cleef, the gravitas-blessed, elven-eared New Jersey native who starred in more spaghettis than any of his fellow American tourists. Sergio Leone’s casting of Van Cleef in For a Few Dollars More did for the actor’s career what the international popularity of spaghetti films temporarily did for the Western—gave it new life.”

“These were all formidable films,” writes Alex Cox in the New York Times. “Visually extremely striking, aurally distinctive, wonderfully acted, violent, mystifying, perversely inspirational. Watching these films—so individual, so strange, frequently so bad—encouraged me to think I might make films just like them, in the cowboy hovels of the same surreal Spanish desert. When it came about in 1986, my own spaghetti western, Straight to Hell (a digital redux released last year as Straight to Hell Returns), was nowhere near as good as even the worst of these films. But it was shot in the same desert where they made For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad & the Ugly, just across the street from the Leone ranch. And it was the most fun, and the best experience, for me, of all the films I’ve made.”

Update: Turns out we get an online essay on Spaghetti Westerns from J. Hoberman after all. The opening paragraph at the NYRblog: “‘Every aesthete in New York, Paris, and London wants to make a musical,’ film critic Andrew Sarris joked at the height of French New Wave. As the Vietnam War escalated, one could have made a parallel assumption about another popular genre: Every Marxist intellectual wants to write a Western. The most notable was Franco Solinas (1927–1982), a teenaged partisan and longtime member of the Italian Communist Party, journalist for the Communist newspaper L’Unità, and author of Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano, Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers, and Costa Gavras’s State of Siege (to name a few). Solinas worked on four Spaghetti Westerns… contributing to this wildly commercial and equally disreputable mode as decisively as director Sergio Leone or composer Ennio Morricone.”

Updates, 6/2: “Influenced like his friend Leone by [Akira Kurosawa’s] Yojimbo, the former film critic Corbucci (1927-90) came to Django after assisting Roberto Rossellini, directing ‘peplums,’ writing comedies, and directing several experimental Westerns.” Graham Fuller at Artinfo: “On Django, which inspired one official sequel (in 1987) and bred some thirty unofficial offspring, he perfected the blunt graphic style and simplistic (a)moral tone that characterizes Spanish-language Western comic books, though its pessimistic streak betokens existentialism. Where the hell can Django ride off too, with or without Maria, except to fresh hells? Not that he’s much more of a flesh-and-blood creation than Yul Brynner’s robot gunslinger in Westworld.”

Ben Parker, though, writing for Artforum, sees Django as emblematic of all the genre’s failures: “Just as Euripides (history’s first hack) looked at the plays of Sophocles and Aeschylus and saw only eye gougings and bathtub axings, which he sought to amplify, Django appropriates the ‘dark’ tropes of late-1950s Hollywood westerns (Anthony Mann’s The Man from Laramie [1955] and Edward Dmytryk’s Warlock [1959]) and empties them of psychology and nuance. Where James Stewart or Henry Fonda brought a kind of desperate, embarrassed sadism to the self-righteousness of the Law of the West, Django‘s Franco Nero (badly dubbed) is without the kind of principles that can really get a man in trouble. Among the spaghetti westerns, this quality of being pushed beyond decency by an incensed, bitter claim is achieved only by Nero himself in Enzo Castellari’s very late Keoma (1976), and by Henry Fonda in Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). But as Django, Nero is unmoored and unmotivated—driven by a kind of general, free-floating revenge. Perhaps it is this detachment and lack of specificity in the character that opened the door to so many sequels and rip-offs.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.